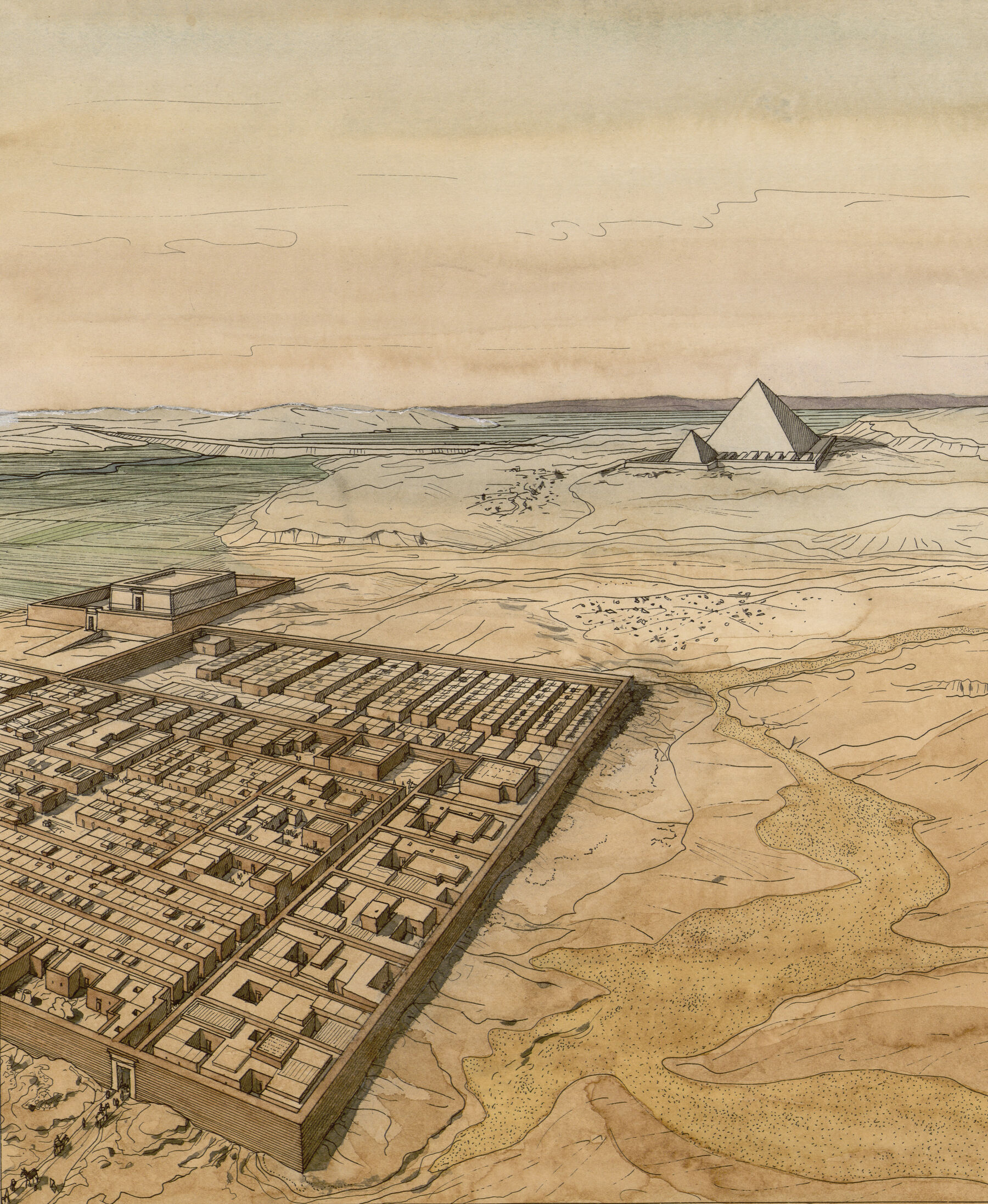

Since the Senusret Collection was named after the village Hetep-Senusret and its refined artifacts, the town will serve as a point of departure for this essay on daily life (Figure 2.1).1 Hetep-Senusret is referred to by its modern names, Lahun, El-Lahun, and Illahun. William Flinders Petrie, who visited the site in 1887, misheard the modern name of the area as Kahun and that name also stuck.2 For the sake of simplicity, we will call Hetep-Senusret by the name of the nearest modern settlement, Lahun.

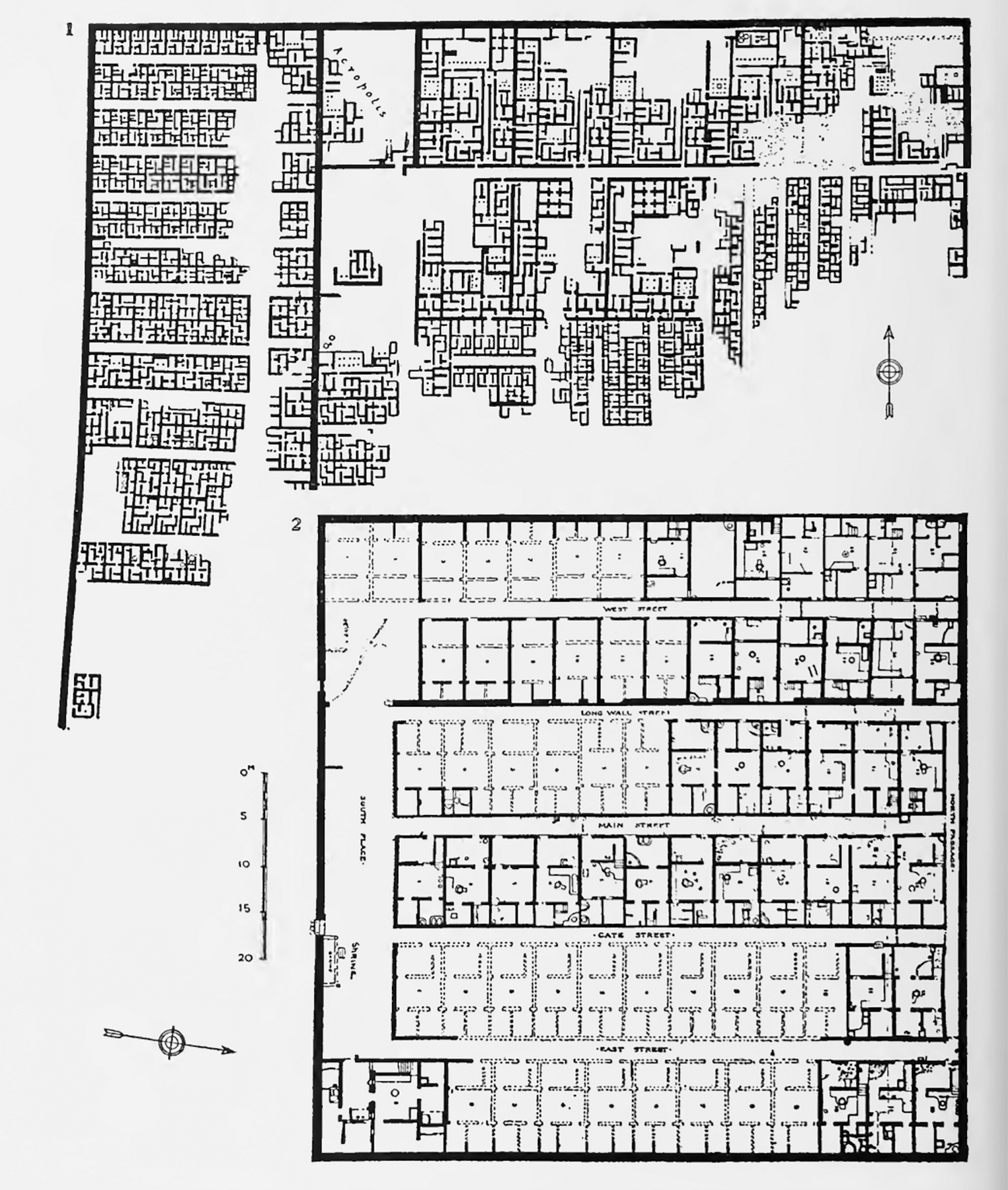

Everyday life at Lahun revolved around the pyramid complex and cult of King Senusret II, who founded the village. Petrie excavated the site in 1889 and 1890 and mapped the entire plan of the village, except for the southeastern part that was destroyed by modern farmland reclamation (Figure 2.2).3 A six-meter wall, roughly nine feet thick, surrounded the town. A north–south wall divided the town into two unequal portions: a larger square with “mansions” in the north, and lesser portion with smaller houses to the south and west. The smaller homes had a single door from the street that led to a central room flanked by two side rooms, some with painted walls.4 Initially, these houses probably accommodated pyramid workers and support staff who conducted and administered construction work at the royal mortuary complex. In the town’s smaller section, the southern blocks may have accommodated temple personnel while they were on duty.5 The larger eastern part functioned as a typical Middle Kingdom regional center.6 The mansions there could have as many as seventy rooms for extended family and staff, with ample storage facilities for grain.7

Situated on an elevated limestone outcrop is what Petrie called the “acropolis” on top of which was a large mud-brick villa. The acropolis lies at the beginning of the northern row of mansions and had a commanding view of the town. Petrie identified the villa as a temporary royal residence, but other scholars suggest it was the village mayor’s or local governor’s residence.8 To its south lies a temple complex.9 In its heyday between 1845–1750 BCE, the village’s size at roughly 23.5 acres, with a population of between 3000–9000 Egyptians.10

Many artifacts in this catalog illustrate the types of objects one might find in a worker’s village. In the western village, stone masons kept their bronze tools, wooden hammers (cat. no. 1), and smiths smelted metal using earthenware molds.11 Set squares and plumbs were used to face the stone blocks for the king’s pyramid complex.12 Boxes crafted from acacia wood stored cosmetics like hematite and juniper berries to color women’s cheeks and lips.13 Gray galena (mineral lead sulfide) and green malachite (mineral copper carbonate) were ground on palettes and applied by kohl sticks to the eye rim and eyelashes. Chests contained combs, alabaster unguent jars, ivory kohl pots, and ointment spoons (cat. no. 5). Men and women wore jewelry, and industry developed in the town to supply this need. Artists made beads of carnelian and faience, perforating them with a bow drill, using sand as an abrasive (cat. nos. 12, 14).14 The Egyptians removed body and facial hair with razors and tweezers and applied oils and unguent to smell good. Mirrors polished to a high sheen aided personal grooming. Wood and woven rush beds with headrests kept the sleeper’s head cool and safe from scorpions and spiders (cat. no. 4). Deliveries of flax and weaving equipment like loom beams, heddle jacks, and rippling combs produced clothes, linen bandages and sheets (like the covering on the mummy of Taosiris), and nets for fishing.15 Wooden molds were used to create mud bricks for the pyramid of Senusret II.16 Pottery was fired in kilns to make it suitable for storing food and beverages.17

Scribes recorded village life, construction work, and temple administration on papyri and fastened them with mud seals (cat. no. 3). The number of papyri and seals found in Lahun suggests that many villagers were scribes. The discovery of a writing tablet, a counting board, and a papyrus containing nine model letters corrected in red ink confirm that there was a school for students in or around Lahun.18

The inhabitants grew, harvested, and threshed barley to make bread and beer. Grain was given to the town brewer and used to brew beer in the household.19 Beer was a staple of everyday village life, but also used medicinally.20 Physicians used implements to diagnose symptoms and mix treatments for illnesses (cat. no. 18). Some of these remedies predated Hippocratic and Galenic medical procedures of fumigation and massage with oil.21 Villagers grew date palms and fig trees (Figure 2.3). Food was sweetened with carob, dates, and honey, and spiced with garlic and black cumin.22 Kitchen gardens grew vegetables such as peas, beans, onions, chate melons, garlic, and fruits like grapes and watermelons.23 Scented plants like jasmine, tree bark, leaves, and roots were mixed with resin and oil to make cosmetics, unguents, and incense.24 Fish from the Nile were an important part of the diet.25 Animals for work and food were likely kept nearby.26 The villager’s basic diet revolved around bread, beer, onions, fish, and whatever vegetables and fruit trees they grew in their garden. The wealthy had their fill of meat and fowl along with the products from their agricultural estates. Priests received food and drink from the temple altars after the completion of temple rituals.

In the immediate area of Lahun were temples to the god of embalming Anubis, the crocodile god Sobek, and the cult of the deceased ruler Senwosret II, who was considered divine upon death.27 A temple to “Sopdu Lord of the East” may also have resided on the acropolis.28 Within temples, heka, or creative power, was present in the architectural forms, which recreated the beginning of the world. Daily temple rituals conducted by elite priests manipulated heka so that the gods, manifested within their cult statues, would preserve the order of the universe. On temple walls, representations were activated using the Ceremony of the Opening of the Mouth.29 Statues and reliefs of the king (cat. no. 21), the elite (cat. no. 25), and the gods (cat. nos. 27–43) were set up in temples to act as participants in daily rituals and celebrations.

Heka, or creative power, was also available to Egyptians who could control and manipulate it through the correct incantations, charged substances, and rituals. 30 Simple spells said over chippi, and other objects protected individuals from sickness and harm by blocking negative energy (cat. no. 17). Offering to domestic deities like Bes and Tauert in household shrines protected the vulnerable, especially children and pregnant women. Amulets and jewelry in specific colors and stones influenced the wearer’s fortune.

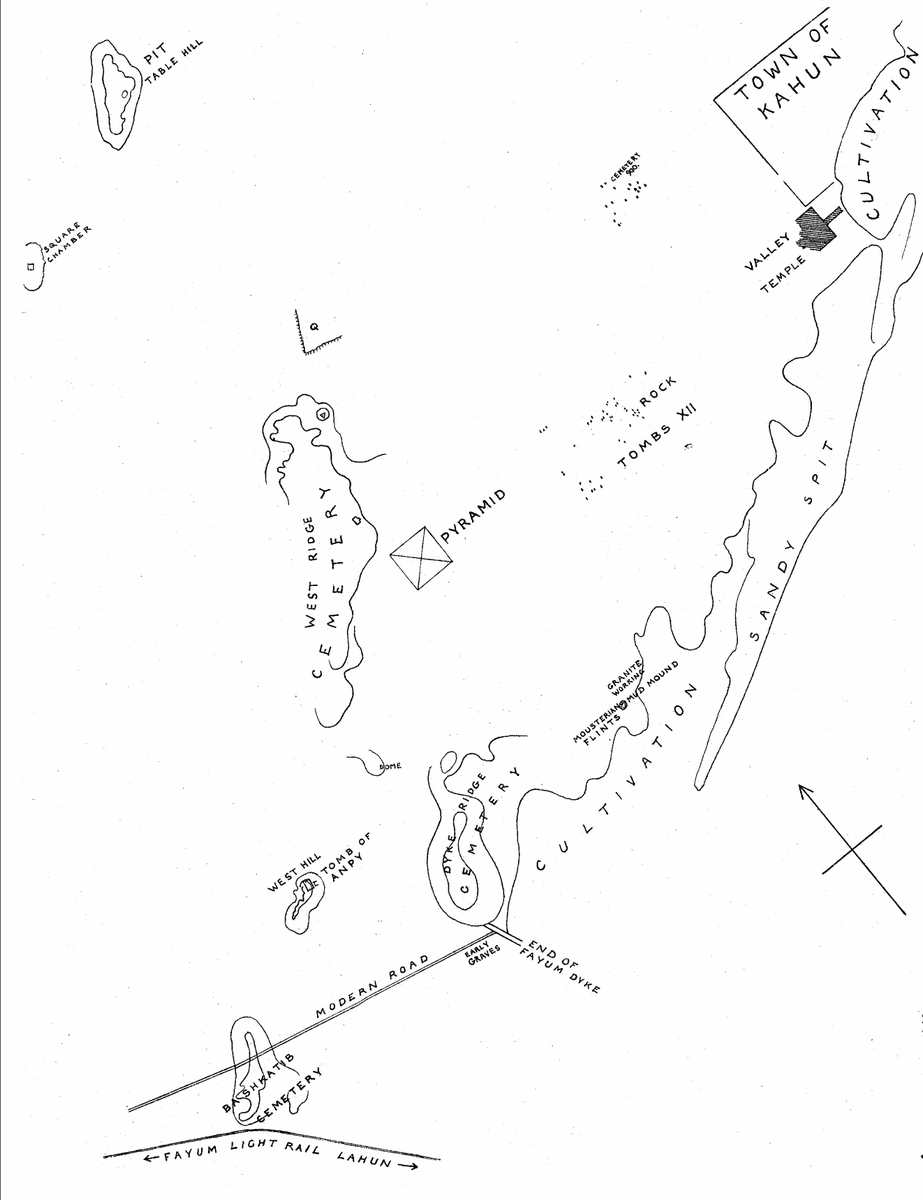

An attendance list from Lahun gives the names and dates of festivals celebrated by the townspeople. These included national celebrations like the Sokar Festival or the regional festivals of Sobek and the “sailing of Hathor.”31 Some villagers went on pilgrimages to Abydos to participate in the public festival that reenacted the death and rebirth of the god Osiris.32 Visitors erected commemorative stelae and statues (cat. no. 20). In the sacred sites of Egypt, pilgrims offered animal mummies and coffins (cat. nos. 52–57). When villagers at Lahun died, they were buried in the nearby “pyramid cemetery” that included tombs in the “West Hill” to the northwest, the rocky rise of the “West Ridge” further west, and shaft tombs in “Cemetery 900,” all of which were heavily plundered (Figure 2.4).33 They were buried with goods needed for their eternal life (see the essay “The Good Burial”).

The Middle Kingdom town of Lahun was like any other Middle Kingdom town in Egypt. Villagers worked, lived, prayed, and died. They were sustained by food, drink, and their objects of daily use. They worshiped in home shrines, priests conducted rituals in temples, villagers sang and danced during festivals, and gave votives to the gods in their temples and shrines so they would hear their prayers. Petrie captured the essence of Lahun when he wrote, “so intimate may you now feel walking their streets, and sitting down in their dwellings, that I shall rather describe them as a living community than as historical abstractions.”34

-

There are two toponyms for the town, Hetep-Senusret and Sekhem-Senusret. The former is the name of the larger eastern part of Lahun, and the latter refers to the western part of the town (Horváth 2009). For simplicity, we will refer to the town as Hetep-Senusret since it was the the original name of the town founded by Senwosret II (specificially Hetep-Senusret-maa-kheru, “Satisfied is King Senwosret, justified”). ↩︎

-

Petrie, W. M. Flinders, Guy Brunton, and Margaret Alice Murray. 1923. Lahun II. British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Egyptian Research Account [33] (26th year). London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt; Bernard Quaritch.. ↩︎

-

Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1890. Kahun, Gurob and Hawara. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner., Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1891. Illahun, Kahun and Gurob: 1889-90. London: David Nutt.. ↩︎

-

Gallorini, Carla. 1998. “A reconstruction of Petrie’s excavation at the Middle Kingdom settlement of Kahun.” In Lahun studies, edited by Stephen Quirke, 42-59. Reigate: SIA.. ↩︎

-

Quirke, Stephen. 1997. “Gods in the temple of the king: Anubis at Lahun.” In The temple in ancient Egypt: new discoveries and recent research, edited by Stephen Quirke, 24-48. London: British Museum Press. ↩︎

-

Horváth, Zoltán. 2015. “The antiquities of Lahun.” In In the shadow of a pyramid: the Egyptian collection of L. V. Holzmaister, edited by Jana Martínková and Pavel Onderka, 65-74. Prague: National Museum.. ↩︎

-

Arnold, Dieter. 2003. The encyclopaedia of ancient Egyptian architecture. Translated by Sabine H. Gardiner and Helen Strudwick. London: I. B. Tauris.. ↩︎

-

Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1891. Illahun, Kahun and Gurob: 1889-90. London: David Nutt.; Moeller, Nadine. 2017. "The foundation and purpose of the settlement at Lahun during the Middle Kingdom: a new evaluation. In Essays for the library of Seshat: studies presented to Janet H. Johnson on the occasion of her 70th birthday, edited by Robert K. Ritner, 183-203. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.. ↩︎

-

Moeller, Nadine. 2016. The Archaeology of Urbanism in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.. See Petrie, W. M. Flinders, Guy Brunton, and Margaret Alice Murray. 1923. Lahun II. British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Egyptian Research Account [33] (26th year). London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt; Bernard Quaritch.. ↩︎

-

See discussions in Kemp, Barry J. 1989. Ancient Egypt: anatomy of a civilization. London; New York: Routledge.; Moeller, Nadine. 2017. "The foundation and purpose of the settlement at Lahun during the Middle Kingdom: a new evaluation. In Essays for the library of Seshat: studies presented to Janet H. Johnson on the occasion of her 70th birthday, edited by Robert K. Ritner, 183-203. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.. ↩︎

-

Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1890. Kahun, Gurob and Hawara. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner.. ↩︎

-

Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1890. Kahun, Gurob and Hawara. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner. ↩︎

-

Hematite is an iron oxide and the main ingredient of red ochre. Image in David, Rosalie. 2003. Handbook to life in ancient Egypt, Revised ed. New York: Facts On File. ↩︎

-

See David, A. Rosalie. 1986. The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt: A Modern Investigation of Pharaoh’s Workforce. London and New York: Routledge.; and UCL 7085 (bow) and 7084 (drill) excavated by Petrie from Kahun. ↩︎

-

David, A. Rosalie. 1986. The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt: A Modern Investigation of Pharaoh’s Workforce. London and New York: Routledge.; Nicholson, Paul T. and Ian Shaw, eds. 2000. Ancient Egyptian materials and technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. , ↩︎

-

Nicholson, Paul T. and Ian Shaw, eds. 2000. Ancient Egyptian materials and technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . ↩︎

-

See Manchester Museum Acc. No. 51. ↩︎

-

Szpakowska, Kasia M. 2008. Daily life in ancient Egypt: recreating Lahun. Oxford: Blackwell.. ↩︎

-

Collier, Mark and Stephen Quirke. 2006 The UCL Lahun Papyri: accounts. BAR International Series 1471. Oxford: Archaeopress.. ↩︎

-

Cf: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/78710 no XXIV. The Lahun Gynecological Papyrus mentions a concoction of sweet beer, date syrup, new oil, and incense for pregnancy problems. ↩︎

-

Smith, Lesley. 2011. "The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus: ancient Egyptian medicine. BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health 2011, no. 37: 54-55.. ↩︎

-

See evidence of beekeeping David, A. Rosalie. 1986. The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt: A Modern Investigation of Pharaoh’s Workforce. London and New York: Routledge.; Nicholson, Paul T. and Ian Shaw, eds. 2000. Ancient Egyptian materials and technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . ↩︎

-

Newberry in Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1890. Kahun, Gurob and Hawara. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner.; Nicholson, Paul T. and Ian Shaw, eds. 2000. Ancient Egyptian materials and technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . ↩︎

-

Nicholson, Paul T. and Ian Shaw, eds. 2000. Ancient Egyptian materials and technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ↩︎

-

Collier, Mark and Stephen Quirke. 2002. The UCL Lahun papyri: letters. BAR International Series 1083. Oxford: Archaeopress.. ↩︎

-

Moeller, Nadine. 2017. "The foundation and purpose of the settlement at Lahun during the Middle Kingdom: a new evaluation. In Essays for the library of Seshat: studies presented to Janet H. Johnson on the occasion of her 70th birthday, edited by Robert K. Ritner, 183-203. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.. ↩︎

-

Quirke, Stephen. 1997. “Gods in the temple of the king: Anubis at Lahun.” In The temple in ancient Egypt: new discoveries and recent research, edited by Stephen Quirke, 24-48. London: British Museum Press; Moeller, Nadine. 2017. "The foundation and purpose of the settlement at Lahun during the Middle Kingdom: a new evaluation. In Essays for the library of Seshat: studies presented to Janet H. Johnson on the occasion of her 70th birthday, edited by Robert K. Ritner, 183-203. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.. ↩︎

-

Kemp, Barry J. 1989. Ancient Egypt: anatomy of a civilization. London; New York: Routledge.; Horváth, Zoltán. 2009. “Temple(s) and Town at El-Lahun. A Study of Ancient Toponyms in the el-Lahun Papyri.” In Archaism and Innovation. Studies in the Culture of Middle Kingdom Egypt, edited by Silverman, D. P., Simpson, W. K., and Wegner, J. W., 171–203. New Haven and Philadelphia: Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Yale University; University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.. ↩︎

-

Goyon, Jean-Claude. 1972. Rituels funéraires de l’ancienne Égypte. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf. ↩︎

-

Ritner, Robert K. 2008. The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical Practice. SAOC 54. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.. ↩︎

-

Szpakowska, Kasia M. 2008. Daily life in ancient Egypt: recreating Lahun. Oxford: Blackwell.. ↩︎

-

Szpakowska, Kasia M. 2008. Daily life in ancient Egypt: recreating Lahun. Oxford: Blackwell.. ↩︎

-

Petrie, W. M. Flinders, Guy Brunton, and Margaret Alice Murray. 1923. Lahun II. British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Egyptian Research Account [33] (26th year). London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt; Bernard Quaritch.. ↩︎

-

Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1890. Kahun, Gurob and Hawara. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner.. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Arnold 2003

- Arnold, Dieter. 2003. The encyclopaedia of ancient Egyptian architecture. Translated by Sabine H. Gardiner and Helen Strudwick. London: I. B. Tauris.

- Collier and Quirke 2002

- Collier, Mark and Stephen Quirke. 2002. The UCL Lahun papyri: letters. BAR International Series 1083. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Collier and Quirke 2006

- Collier, Mark and Stephen Quirke. 2006 The UCL Lahun Papyri: accounts. BAR International Series 1471. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- David 1986

- David, A. Rosalie. 1986. The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt: A Modern Investigation of Pharaoh’s Workforce. London and New York: Routledge.

- David 2003

- David, Rosalie. 2003. Handbook to life in ancient Egypt, Revised ed. New York: Facts On File.

- Gallorini 1998

- Gallorini, Carla. 1998. “A reconstruction of Petrie’s excavation at the Middle Kingdom settlement of Kahun.” In Lahun studies, edited by Stephen Quirke, 42-59. Reigate: SIA.

- Goyon 1972

- Goyon, Jean-Claude. 1972. Rituels funéraires de l’ancienne Égypte. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf.

- Horváth 2009

- Horváth, Zoltán. 2009. “Temple(s) and Town at El-Lahun. A Study of Ancient Toponyms in the el-Lahun Papyri.” In Archaism and Innovation. Studies in the Culture of Middle Kingdom Egypt, edited by Silverman, D. P., Simpson, W. K., and Wegner, J. W., 171–203. New Haven and Philadelphia: Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Yale University; University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

- Horváth 2015

- Horváth, Zoltán. 2015. “The antiquities of Lahun.” In In the shadow of a pyramid: the Egyptian collection of L. V. Holzmaister, edited by Jana Martínková and Pavel Onderka, 65-74. Prague: National Museum.

- Kemp 1989

- Kemp, Barry J. 1989. Ancient Egypt: anatomy of a civilization. London; New York: Routledge.

- Moeller 2016

- Moeller, Nadine. 2016. The Archaeology of Urbanism in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Moeller 2017

- Moeller, Nadine. 2017. "The foundation and purpose of the settlement at Lahun during the Middle Kingdom: a new evaluation. In Essays for the library of Seshat: studies presented to Janet H. Johnson on the occasion of her 70th birthday, edited by Robert K. Ritner, 183-203. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- Nicholson and Shaw 2000

- Nicholson, Paul T. and Ian Shaw, eds. 2000. Ancient Egyptian materials and technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Petrie 1890

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1890. Kahun, Gurob and Hawara. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner.

- Petrie 1891

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1891. Illahun, Kahun and Gurob: 1889-90. London: David Nutt.

- Petrie, Brunton, Murray 1923

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders, Guy Brunton, and Margaret Alice Murray. 1923. Lahun II. British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Egyptian Research Account [33] (26th year). London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt; Bernard Quaritch.

- Quirke 1997

- Quirke, Stephen. 1997. “Gods in the temple of the king: Anubis at Lahun.” In The temple in ancient Egypt: new discoveries and recent research, edited by Stephen Quirke, 24-48. London: British Museum Press

- Ritner 2008

- Ritner, Robert K. 2008. The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical Practice. SAOC 54. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- Smith 2011

- Smith, Lesley. 2011. "The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus: ancient Egyptian medicine. BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health 2011, no. 37: 54-55.

- Szpakowska 2008

- Szpakowska, Kasia M. 2008. Daily life in ancient Egypt: recreating Lahun. Oxford: Blackwell.