Laeïla Adjovi (Beninese/French, b. 1982) and Loïc Hoquet (French, b. 1985)

Wings, the physical mechanism by which birds fly, are a symbol of freedom and an emblem for soaring high and achieving the impossible. As inspiring as the metaphorical associations with wings can be, it is equally devastating to imagine a creature with clipped wings. Clipped wings represent the figure that was born to fly, but is confined to the ground; that could soar above, but is relegated to walking; that could be free, but is now imprisoned. Laeïla Adjovi and Loïc Hoquet’s embodied Africa, as expressed in their photo series Malaïka Dotou Sankofa, exposes the continent as one that has long been displaced by the exploitation and expectations of Europe, America, Russia, and China, who insist she stand on her own two feet, and not fall into the traps of corruption, economic despair, and disease. But these expectations hold her down: she is squeezed into Western dress, her natural and human resources exploited, and depicted as violent, primitive, and outdated.

Malaïka Dotou Sankofa won the Léopold Sédar Senghor prize at the Dak’Art Biennale in 2018. The goal of Dak’Art, which began in 1989, was to showcase the continent’s visual and literary arts, as an expression of Senegal’s first president Senghor’s vision for a pan-African cultural revolution. While this biennial has been and remains critical to raising the profile of many contemporary artists from Africa and the diaspora, the system also contributes to a dysfunctional global art economy.1 Dak’Art, which has always worked to promote contemporary artistic production on the continent, participates in a colonial paradigm based on the Venice Biennale and the World’s Fairs of the nineteenth century. Just as Yinka Shonibare is visually and intellectually playing with colonial traps and critiquing them, Adjovi and Hoquet’s work is a prime illustration of how the international art system continues to view Africa though a telescopic Western lens, deepening the contradictions Malaïka personifies.

The wings of Malaïka Dotou Sankofa seem to represent the complexities of the African continent. The name itself is a combination of Wolof, Swahili, Fon, and Twi, playing with the movement of language across the geography of the continent and thus its shared and distinct cultural attributes. Malaïka, Arabic for “queen,” means “angel” in Swahili, which shares many linguistic characteristics with Arabic. But “malaaka” also means angel in Wolof, the lingua franca in Senegal. “Dotou,” in Fon, spoken by the Fon in present day Benin, means “stay strong,” or “determined."2 Sankofa, perhaps one of the most important concepts in the Akan culture of Ghana, means “go back and take it” in Twi. The concept is often visually represented by a glyph of a bird that cranes its neck back, symbolizing the need to understand the past in order to plan for the future.3 The wings borne by Malaïka Dotou Sankofa are a physical rendering of these meanings. They are constructed of a patchwork of Manjak and Wax Hollandais, fabrics that bear the weight of the complex histories of the continent, including the colonial past, to create something that should allow the continent to soar. The wings point to the patchwork-style dress of the Baye and Yaye Fall, a sufi order in Senegal.

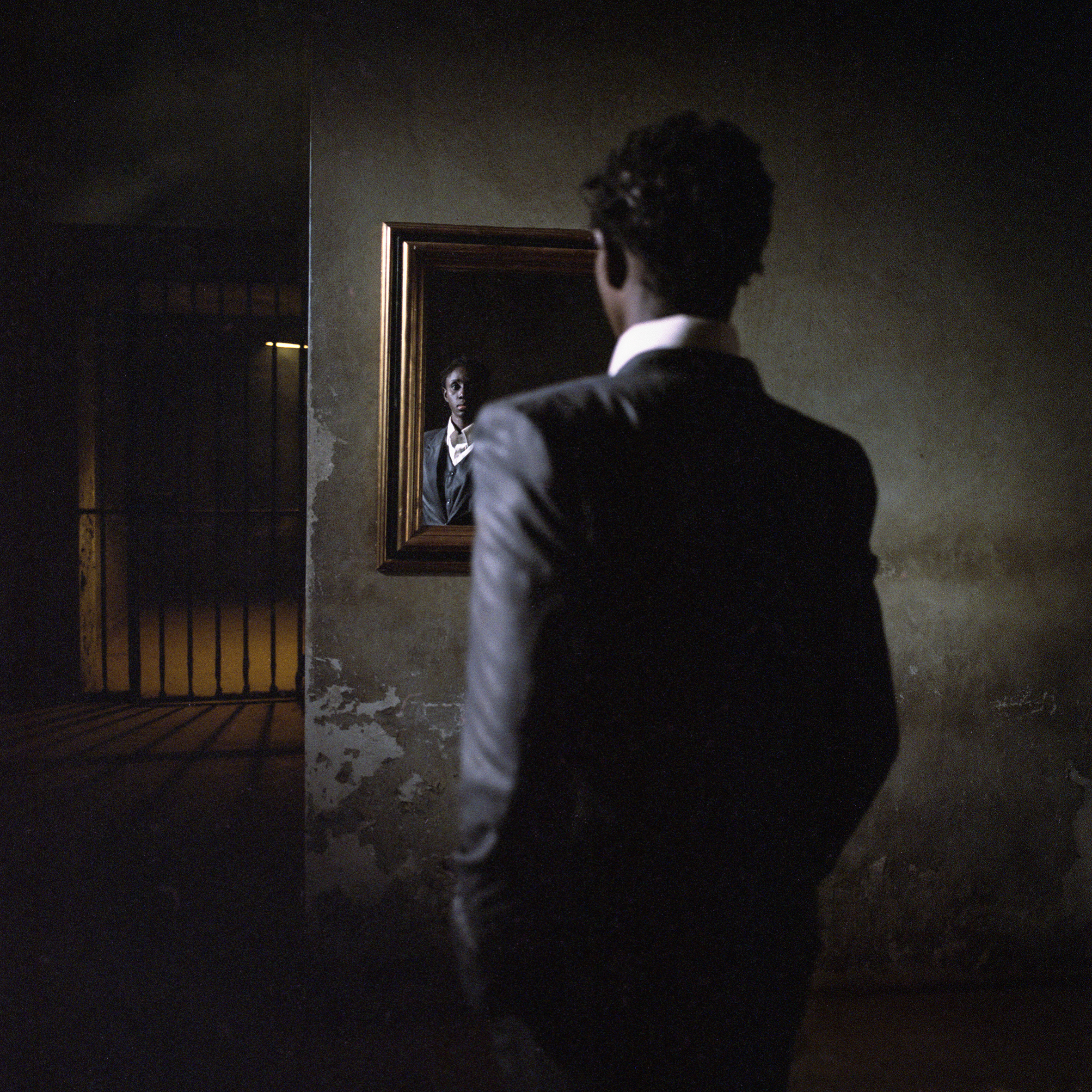

The setting for this series is unmistakably a ruin. The walls of the Palais de Justice, the old colonial courthouse, pale and grubby, are smudged, pocked, and peeling. The floor is concrete or matted carpet, the debris and grime palpable. Light barely interrupts the gloom, and when it does creep into the background of the frame (ominously yellow, from behind bars) or from offscreen, its source invisible, it rakes across the grime to reveal the hardness of every fraying surface. To look into these rooms is to feel that they are airless. The viewer cannot be blamed for a visceral impulse to want to get away: nobody should be in here. Probably nobody has been in here for years.

It is an initial contradiction, then, that these rooms are not unpopulated. The eponymous Malaïka Dotou Sankofa, brought to life by Senegalese dancer and choreographer Marie Agnès Gomis in a three-piece suit with a pair of colorful wings strapped to her back, wanders the environs. In one image, she balances atop what seems to be a stack of disintegrating books, her appearance human in some senses—hands in pockets, sleeves rolled up—and birdlike in others; knee bent, the right foot touches the back of the left leg, a gesture that could be a bored person’s anxious fidgeting, or the prehensile perch of a flamingo. The wings lend any more-than-human interpretation credence: in other images they wrap around Malaïka’s body as she crouches on the armrest of a row of identical, institutional high-backed wooden chairs, the cream-colored upholstery peeling away from their bases. The wings take on a character of their own, both sprouting from a person’s back but not fully of that person. They shelter Malaïka as she broods, but if deployed to full width they would span four chairs even as she fills only one.

On display, the wings spread nearly twelve feet across in the posture a winged creature stoops in as it accelerates into flight. From below, each feature of manjak or Wax Hollandais is visible, spiky geometric cornflower blues or mossy paisleys, with magenta and lemon-yellow accents. As a museum object, the wings are posed, mounted on a wall like a trophy, where they are also spread out, emerging from a façade. Distinct from a controlled museum setting, however, the exposed brick wall—with loose plaster threatening to slide off the surface, making the damage more extensive still—and shards of material scattered on the floor underneath it tell a story of Malaïka Dotou Sankofa’s demise, or escape. Toward the extremes of the wings, a few feathers tremble, their shapes blurring.

In a poem composed to accompany the photographs, Adjovi writes,

My name is Malaïka Dotou Sankofa.

I don’t know how long I have been kept here.

I was told it was for my own good

To never try to escape

That the skies would be all gloom

Storm, squalls and night

So I stayed

But now

Freedom feels just a dream away

My name is Malaïka.

I am not trying to be the center of the world

Only my own

I am being told to develop

Take off. Emerge. Grow

All without stepping out of the box

force-fed with empty concepts,

watermelon and fried chicken

So I started a hunger strike

I hear revolution rumble

in my empty stomach

My name is Dotou.

This drab old suit

is my sole attire

One uniform

impossible to refute

Fortunately, seams are bursting

I have learnt to sew

I am no longer afraid to outgrow it

and then patch up my own suit

My name is Sankofa.

In my cell

in myself

I have learnt to tame words and Letters

without ever betraying the tongue

I can read through history books' stains

and write on typewriters nested in barbed wire

From now on, no one can turn off my Lights

I will dance high on the ruins of yesterday

on the tombs of plunderers in the graveyard of their clichés.

My name is Malaïka Dotou Sankofa.

The composition extends the meaning of the photos beyond their ruinous setting by creating a sense of futurity. Malaïka, as she wanders her “cell” in the “ruins of yesterday,” has developed self-awareness, and resentment. She has claimed credit for constructing the colorful wings, making something powerful and freeing. From the scraps of colonial industry, she has reconstructed self-determination, and powered by that potentiality, she will eventually break free.4

Notes

-

Ugochukwu-Smooth Nzewi, “The Dak’Art Biennial in the Making of Contemporary African Art, 1992-Present” (PhD diss., Emory University, 2013), 3. ↩︎

-

Sometimes called niahaas, which translates to “patchwork” in Wolof. See Nicole Crowder, “The roots of fashion and spirituality in Senegal’s Islamic brotherhood, the Baye Fall,” The Washington Post, January 23, 2015, [https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/in-sight/wp/2015/01/23/the-roots-of-fashion-and-spirituality-in-senegals-islamic-brotherhood-the-baye-fall]{.underline}. See also “Laeila Adjovi - WINNER,” Art Africa, 2017, [https://artafricamagazine.org/laeila-adjovi-winner-2017]{.underline}. ↩︎

-

Nii O. Quarcoopome, “Art of the Akan,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 23, no. 2 (1997): 141. ↩︎

-

Laeïla Adjovi, “From Malaïka to Yemoja: A Reflection on Breaking Free,” Nix Mann Lecture, Michael C. Carlos Museum, Atlanta GA, February 6, 2022. ↩︎