Thameur Mejri (Tunisian, b. 1982)

On December 17, 2010, Mohamed Bouazizi, a produce vendor from Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia, self-immolated in the street outside the governor’s office. The immediate cause was the harassment he had faced from local authorities, but the larger societal implications were the corruption that led to deep economic disparities throughout the country. The humiliation of Bouazizi was part of both a larger campaign of dehumanizing citizens, and governmental corruption through dictatorships across the Maghreb and into the Arabian Peninsula. By the time the young street vendor died, two and a half weeks later, his protest had begun a revolution known as the Arab Spring, which spread across the Arab world, toppling the governments of Tunisia’s Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, and Yemen’s Ali Abdullah Saleh; provoking protests in Morocco, Bahrain, and Algeria; and inciting a civil war in Syria that has lasted more than a decade.

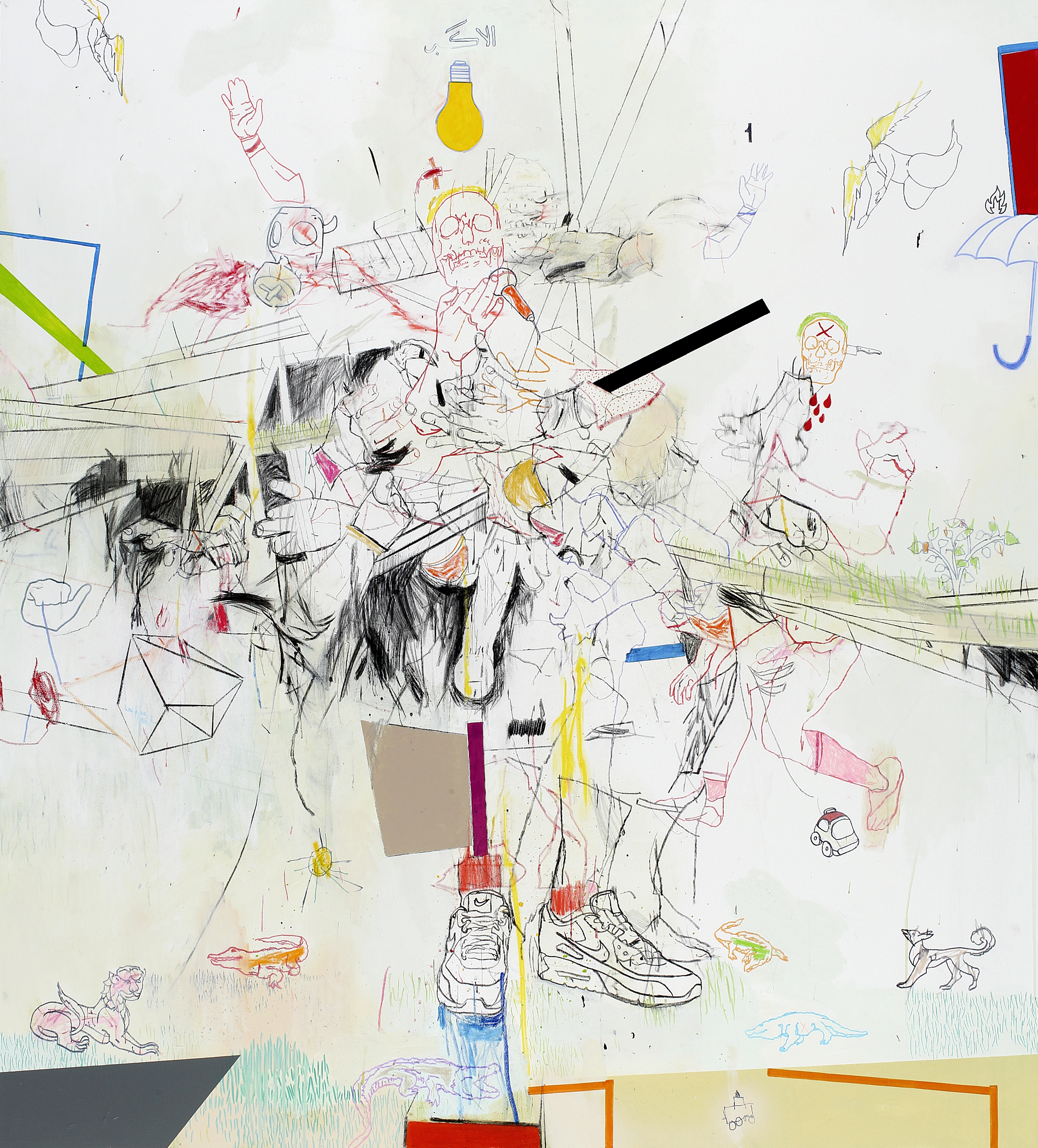

Thameur Mejri dissects the bigotry, violence, and human rights violations of these regimes through disturbing imagery of therianthropic forms, weapons, dismembered bodies, and skulls. The didactic materials from his 2017 exhibition at London’s Jack Bell Gallery described how the “ambivalent characters come in and out of focus as disarticulated figures and objects overlap and converge.”1 This anarchy creates a space in which the viewer’s ordinary world, filled with toys and common household items, is disrupted.

Mejri unpacks the sociopolitical environment that facilitates the violence and destruction in the Maghreb with intense and vivid compositions that “reflect the chaos and turbulence in contemporary society, and the dehumanisation of people by religious and political authorities who control their minds, and are omnipresent in their lives from childhood.”2 Cultural theorist Kwame Anthony Appiah asserts that the horrific treatment of other humans is an acknowledgment of their humanity: “the persecutors may liken the objects of their enmity to cockroaches or germs, but they acknowledge their victims’ humanity in the very act of humiliating, stigmatizing, reviling, and torturing them. Such treatment—and the voluble justifications the persecutors invariably offer for such treatment—is reserved for creatures we recognize to have intentions and desires and projects.”3 We do not torture a cockroach that runs across the kitchen floor even when we intend to kill it; to act with the clear intention to inflict cruelty, to hurt victims, is to recognize their humanness. Mejri was working with these themes in the years leading up to the Arab Spring as he saw the War on Terror, ISIS, and corrupt governments ravaging communities, turning a generation of men into the monsters they were trying to fight.4 The monstrous figures that Mejri depicts are terrifying because they combine beautifully rendered human forms with grotesque aspects such as gas masks, animal heads, severed body parts, and skeletal features, creating threatening hybrids. In this sense, Mejri’s work is in dialogue with the much longer-term project of reconciling how humans could possibly cause pain to other humans on such an inhuman scale.

Mejri describes the faceless monsters and deformed figures in his paintings as “both perpetrators and victims of the destructive powers that seek to dehumanise us, and incite violence. They represent a society, which is fragmented and lost, because it is not based on a solid foundation.”5 The viewer is forced to consider the complexity of societal violence, their own actions and worldviews implicated as facilitating the oppression of others, even when they did not directly perpetrate the action. Philosopher David Livingstone Smith states that “time after time, genocide after genocide, [perpetrators] characterize those whom they wish to harm as less-than-human creatures, and in so doing diminish their moral status to such an extent as to make the commission of the most hideous acts of violence against them permissible or even obligatory.”6

However, Mejri’s work argues that to perpetuate violence one must dehumanize not only the victim, but the perpetrator, too. While this can happen overtly through indoctrination and radicalization, it also happens inconspicuously through toys, demeaning language, and rationalizing acts of brutality. In 2 Inches Away From My Tomb, human parts are surgically affixed to a ram’s head, the fleshy body appears to have too many hands, and the innards are tangled in a heap, a nauseating mass next to banal accessories such as a tie, or a Chuck Taylor high-top.

Powerfully, the figures, toys, and ordinary objects represented in each composition are also twisted, blurring into a grotesque, chaotic, and violent scene that makes the familiar, innocent, and ordinary rather dangerous, frenzied, and scary. Scenes of disorderly motion, strewn with toys, lamps, monitors, gas cans, and chairs, interrupt any sense of space. For Mejri, the militarized and the ordinary already coexist in one horrifying inseparable mass; he has merely made it literal: “War comes from within our own environment — from inside the comfort zone of our homes. The toys and gun-toting cartoon characters represent childhood influences that could make us monsters or good people. The gasoline cans refer to the revolution in Tunisia, which was triggered by a desperate man immolating himself. The dinosaurs and a fly are a reminder that if we carry on with our destructive ways we will be extinct one day, and perhaps the fly will be the only remaining witness of our disastrous stupidity.”7 The banal objects placed alongside the grotesque only serve to amplify the horror and chaos and weaponize the human form.

Notes

-

“Before you Split the Ground,” Thameur Mejri at Jack Bell Gallery, April 7-21, 2017. https://www.jackbellgallery.com/exhibitions/70-thameur-mejri-before-you-split-the-ground/overview/ (accessed May 10, 2021). ↩︎

-

Jyoti Kalsi, “Social and Cultural dynamics in the Arab World,” Gulf News, September 20, 2017. https://gulfnews.com/entertainment/arts-culture/social-and-cultural-dynamics-in-the-arab-world-1.2093264. ↩︎

-

Kwame Anthony Appiah, Experiments in Ethics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008), 144. See also David Livingstone Smith, “Paradoxes of Dehumanization,” Social Theory and Practice 42, no. 2 (April 2016): 428; Smith, “The Problem of Humanity and the Problem of Monstrosity,” 3. https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~rja14/shb20/smith1.pdf (accessed May 12, 2021), draft of the chapter published in The Routledge Handbook of Dehumanization, edited by Maria Kronfeldner (London: Routledge, 2021). David Livingstone Smith cites Adam Gopnik’s article “Headless Horsemen,” about the perpetrators of the Reign of Terror, who suggests that “what motivated the spectacle was exactly the knowledge that the victims were people, and capable of feeling pain and fear as people do. We don’t humiliate vermin, or put them through show trials, or make them watch their fellow-vermin die first. The myth of the mechanical murder is almost always only that.” See Adam Gopnik, “Headless Horseman: The Reign of Terror Revisited,” New Yorker, June 5, 2006. ↩︎

-

See for example Thameur Mejri, “‘You have to take risks’ Tunisian artist Thameur Mejri on politics and painting,” interview by Kim Chakanetsa, Focus on Africa, BBC World Service, April 27, 2017, audio, 3:11, https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p05185sb. ↩︎

-

Kalsi, “Social and Cultural dynamics in the Arab World.” ↩︎

-

Smith, “Paradoxes of Dehumanization,” 416. ↩︎

-

Kalsi, “Social and Cultural dynamics in the Arab World.” ↩︎