Environmental Destruction: From Corporate Opportunism to Disaster Capitalism

Who would want to live in a world which is just not quite fatal? — Paul Shepard1

Art is not, as much as we would like to believe, a primary agent of change. It is not even a secondary agent of change. Rather, according to philosopher Theodore Schatzki, art is a part of the “chains of action” within the constitution of our social life that connects artists to activists who fight to convince legislators to amend policy, and the lawmakers themselves, who can actually create structural change to society.2 This acknowledgement reveals the subtle but important point that living is a networked experience. For example, hearing the science behind climate change must be complemented by seeing the effect in art to create the collective weight of the things you experience, which will ultimately give rise to your worldview. To put it another way, artist Angus Galloway describes artists as the canaries in the coal mines—rather than the owners of the mines or the miners themselves. He warns that we are constantly faced with “new coal mines” that act as threats; therefore, we should listen to the artists who sing.3 Even if it is not the painting or photograph or installation that stops global warming, art, combined with a fuller life experience, including the work of activists, can instigate the conversation that alters the way we think. Artist Yinka Shonibare acknowledges this when he states, “I don’t think that a politician will necessarily immediately change government policy just because they’ve seen my art. I mean I don’t think that’s possible. But art like philosophy can start a debate and then can change thinking and what we then hope is that that thinking becomes political and then becomes policy.”4

The potential for artists to steer the conversation is tempered by a lack of representation of climate change and environmental destruction in the arts. Indeed, novelist Amitav Ghosh contends that climate change is distinctly lacking from literature as a component that drives narrative forward. This is in part because the effects of climate change are often unbelievable, and believability is the cornerstone of fiction. This scarcity in the arts, according to Ghosh, “may well be the key to understanding why contemporary culture finds it so hard to deal with climate change. Indeed, this is perhaps the most important question ever to confront culture in the broadest sense—for let us make no mistake: the climate crisis is also a crisis of culture, and thus of the imagination.”5 Examining environmental destruction through the visual trope of the monster is not exactly what Ghosh had in mind to confront the reality of the situation; indeed he asserts that “to treat [the climate crises] as magical or surreal would be to rob them of precisely the quality that makes them so urgently compelling—which is that they are actually happening on this earth, at this time.” The artists in And I Must Scream, however, take up the gauntlet of placing the viewer in the uncomfortable in between, in which they must confront climate change as a condition of which we are all victims and one that supplies many of our modern comforts.6

We need creatives to explore these issues precisely because we cannot understand them on the scale at which we live. Human geographer Anthony Leiserowitz explains our struggle to comprehend global warming: “climate change itself is an abstraction. You cannot directly experience global climate change by yourself…You can experience specific impacts, but you cannot experience what’s going on around the entire world in the ice, in the oceans, in the biosphere, in the atmosphere.”7

Fabrice Monteiro’s Prophecy series takes up this charge directly by working with Senegalese fashion designer Doulsy to create imposing beasts out of discarded video cassette tape, fishing net, and animal carcasses to demonstrate the way in which waste swells beyond human control. In Prophecy #2 a creature made of polluted waste, oil slick, and bird carcasses emerges from Hann Bay, off Dakar. Zombie-like, she appears to have little control over where she is going or what her ultimate mission is, but she will leave behind a trail of sludge as she infiltrates the homes of local citizens, along the sides of fishing boats and in the bellies of their daily catch, on the backs of crabs that scurry along the shore, and, of course, what was formerly pristine water that had supported the village for several centuries.

Prophecy #8 depicts a warrior made of plastic and fishing nets, brandishing a trophy, a sea turtle shell transformed into her shield. Not only has the increase in industrial waste polluted these beaches, but the influx of commercial fishing industries left refuse behind that has destroyed the livelihood for local residents.

These haunting photographs are a testament to the visible devastation of the industrial complex. Bays are naturally protected from the circulation and volatility of the open ocean, which is why they are perfect for fishing villages but as a result are more susceptible to pollution, because there is no mechanism to filter out the excess waste. This natural feature, combined with an influx of population displaced due to drought, a dearth of economic opportunities, and lack of infrastructure, has been further compounded by the establishment of over 100 industrial processing plants. The pollution itself is caused by residents who have no place to dispose of their waste and the runoff from these plants, which include slaughterhouses dumping blood to food processing plants dumping oil directly into the bay, fertilizer plants that process phosphoric acid, and the commercial fishing companies that have also moved in. After less than half a century the damage is visible across the bay, but also in the physical and economic health of those who live in the community. Respiratory, gastrointestinal, and dermatological issues have correlated directly to increased exposure to contaminated water.8

This is made manifest in an arthropod rising from the point where the slaughterhouse waste runoff meets the sea in Prophecy #3. Diluted blood flows freely from a spout to the right and deep in the background, divided by an ocean wave, is a factory that leaves behind some other kind of toxic effluence. Even the monster appears to struggle for air.

Prophecy does not tell us anything that we do not already know. The impacts of environmental destruction are well-established. In 1896, 76 years after physicist Joseph Fourier discovered the greenhouse effect (Earth’s natural regulation of temperature by the atmosphere trapping the sun’s heat), chemist Svante Arrhenius concluded that industrial-age coal burning increases the greenhouse. Not long after, the link was made that such pollution leads to rising temperatures. In 1965 the Science Advisory Committee under US President Lyndon B. Johnson identified that the greenhouse warming affected by the release of man-made emissions should be taken seriously. This was all before the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was formed in 1988. While their first Assessment Report in 1990 acknowledged that temperatures rose over the last century, the second report, published five years later, determined “a discernible human influence on global climate.”9

The connection between environmental destruction and climate change is undeniable, but the biggest concern is the pace at which ecosystems are being damaged. In Rachel Carson’s oft-cited exposé, Silent Spring, she describes the way in which nature is cruel and difficult but “the environment, rigorously shaping and directing the life it supported, contained elements that were hostile as well as supporting…Given time—time not in years but in millenia—life adjusts, and a balance has been reached. For time is the essential ingredient; in the modern world there is no time…The rapidity of change and the speed with which new situations are created follow the impetuous and heedless pace of man rather than the deliberate pace of nature.”10 Today, we are simply demanding too much of nature, too quickly. This is reinforced by economies based on growth and corporate campaigns that shift the responsibility of protecting the environment away from themselves and onto the consumer. The individual is profoundly burdened with understanding how to do their part to save the planet. Even Ghosh addresses this when he says that “this era, which so congratulates itself on its self-awareness, will come to be known as the time of the Great Derangement.”11 Kenyan-American artist Wangechi Mutu’s 2013 animation The End of Eating Everything depicts a grotesque, eructing form made of industrial waste that consumes everything in its path, screaming in horror and rage. Affirming Carson’s point that balance can win out, the bulbous creature explodes, creating a new opportunity for equilibrium.

Nature will win out at the expense of plants, animals, humans, and our need for economic growth. Governments, corporations, and lobbyists may insist that sacrificing diverse agricultural production, acres of rainforest, fracking, and gas pipelines is necessary for strong economies that can support a growing population, but even this has been debunked. For an economy of growth, addressing climate change is good business: in 2006, the Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change concluded “the estimates of damage could rise to 20% of GDP or more…” while “the costs of action…can be limited to around 1% of global GDP each year.”12 Forget, for a moment, the moral charge and human suffering at the heart of climate change. In a purported economy of growth amid financial motivation, why are these assertions not enough to change the corporate model of sustainability? Artists Kahn & Selesnick create elaborate scenes in their phantastic series Eisbergfreistadt to depict the tenuousness of an economy built on the destruction of nature. In their narrative, in November 1923 an iceberg, sent off course by changing oceanic conditions, ran ashore at the German Port of Lübeck. The locals declare the iceberg a free state in which entrepreneurs and artists seek refuge from, or perhaps an opportunity in, a German market plagued by hyperinflation. The question is whether these are creatives looking to establish a cultural utopia, or “free-market travellers” looking to profit from disaster capitalism.13 In this story, it is not a market collapse that creates a shift in behavior, but rather a raucous party that splits the berg in two, ending the unregulated capitalist experiment.

The parafictional approach employed in Eisbergfreistadt is in line with twenty-first-century anxieties, but the idea that the manufacture of culture and empire is the abuse of nature is ancient. In Pliny’s Natural History, written in 77 CE, he repeatedly repudiates man’s desire for luxury as the abuse of nature. Andrew Wallace-Hadrill writes that “the natural world stands in contrast to and in relationship with the human world. The history of Nature,” according to Pliny, “is thus simultaneously a history of Culture. The Natural History of the earth is by inversion the Unnatural History of Man.”14 He continues that “it is only human abuse that turns the gifts of Nature to weapons of destruction. And yet we repay the earth with ingratitude: and among the signs of our ingratitude is that we ignore its nature.”15 Not respecting our place in the ecosystem and empire is the definition of excessive luxury.

In chapter 37, Pliny describes the gemstone as a perfect creation of nature, which man destroys by cutting, carving, polishing, and wearing it like a trophy: “nature supplies, unasked and ungrudgingly, everything man needs, but that man, blinded by luxuria, abuses nature and turns it into the tool of his own destruction; the function of science is to reveal the proper use of nature and so save mankind.”16 Luxury and, by default, culture are wasteful, and it is the exploitation of nature that leads to the downfall of empires. The Eisbergfreistadt recorded by Kahn & Selesnick is ultimately just this: trying desperately to assert a cultural utopia at the expense of nature.

The way in which climate change and economic growth are interconnected may continue to feel abstract, particularly because corporations and many governments put the majority of the responsibility on consumers, but the effects of environmental destruction are no longer intangible. We have all seen firsthand the end result when deforestation leads to the displacement of virus-carrying animals, causing the worst pandemic in over a century. This may have seemed far away from a US vantage point during the 2013 ebola outbreak, when the direct link was made between displacing disease-carrying bats to deforestation to increase palm oil production, but we are now making the connections that climate change is a public health issue. Climate One host Greg Dalton began a recent podcast in this way: “experts have warned us that COVID-19 is just one example of climate change-related diseases on the rise. And while climate disruption, environmental health and the current pandemic may seem like three distinct problems, to many experts, that’s not the case.”17

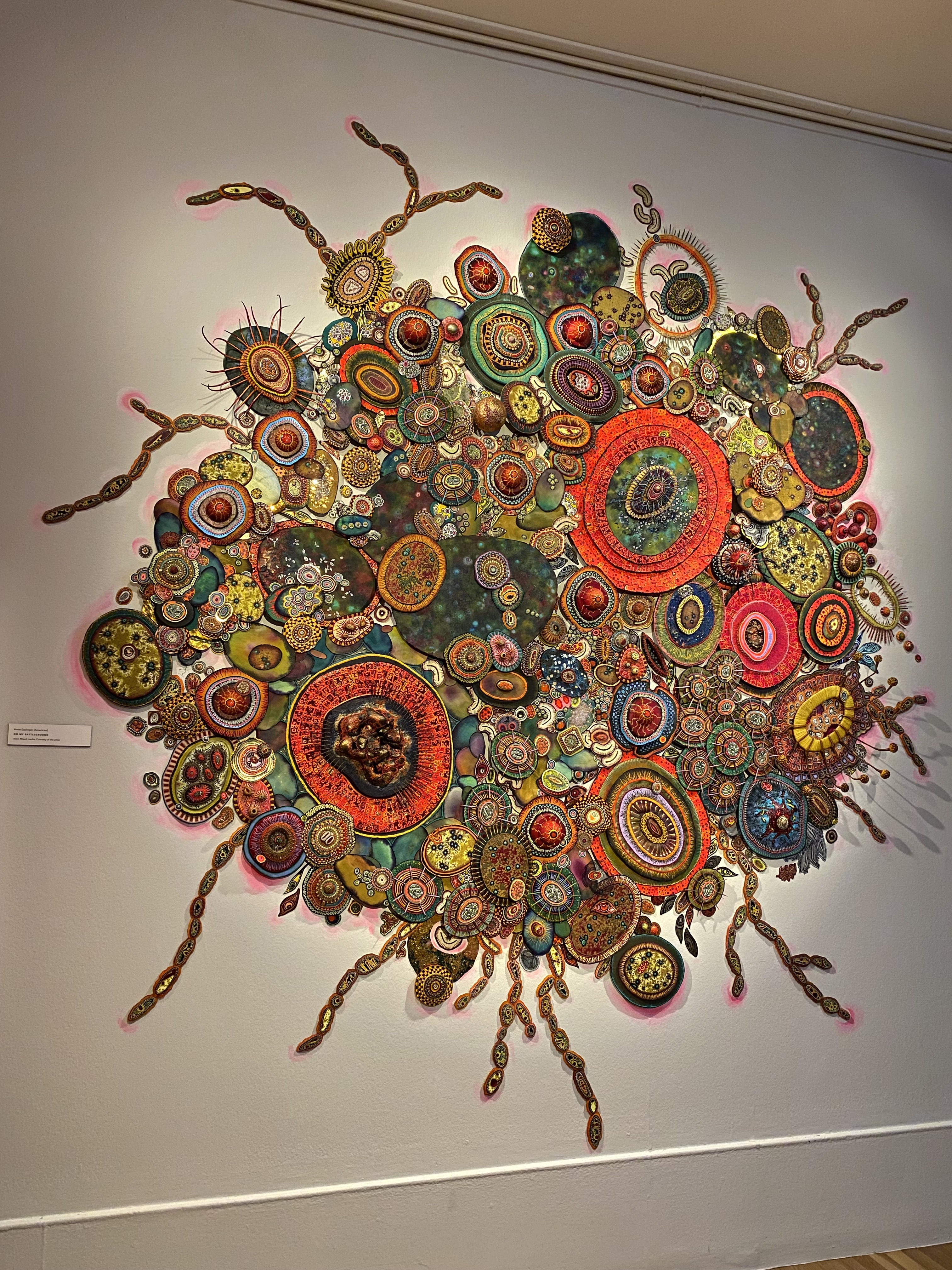

The agglutination of the forms Atlanta-based artist Amie Esslinger depicts represent these “distinct problems” actually becoming intractable. She examines the aesthetic underpinnings of microbiology in virus-like installations in which the disease co-opts the normal processes of cell reproduction. These forms, which feel so familiar as our own circulatory system and cells, transform from something beautiful and life-affirming into something that borders on monstrous and terrifying in a large-scale installation that envelops us. Cellular processes are contained so neatly within our bodies or a petri dish, that, when unleashed, they feel invasive, overwhelming, and horrific. Esslinger’s striking, multimedia compositions elicit the sense that the virus is natural, and of us, while at the same time a creature that can take over and destroy the human race. Aaron Bernstein, a pediatrician and interim director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, describes how a pandemic or the climate crisis cannot be viewed in isolation because it is the societal cracks that cause the intersectionality of these issues to be so apparent. Bernstein asserts that “…the inequities that we allow to fester in society, whether that’s based on racial inequities, [or] other social inequities. These are the fissures through which whether it’s the climate crisis, a pandemic crisis, they thrive in these fissures. They tear them open.”18 One can begin to see in Esslinger’s installations the way in which the forms fill in the cracks. When there is exposed, undeveloped space, it is just a matter of time before the forms fill up those vast openings—and, likewise, disease may disproportionately impact underserved communities, but it is only a matter of time until the repercussions are felt beyond the epicenters.

A relatively recent field of scholarship centers around the ecologies of care, the architecture of environments and resources that focus on caretaking and the wellbeing of communities and individuals. This speaks to a less political version of the Wellbeing Economy Government alliance, a coalition founded by the nations of Scotland, Iceland, and New Zealand that seeks to topple the current metric for a successful government. A wellbeing economy is motivated by a less resource-driven and more experiential metric; this replaces gross domestic product, which focuses solely on growth as the sign of success: “economic models that devalue and obstruct care produce the subjectivities that drive the current climate crisis and the ongoing disruption/destruction of ecosystems, displacing both humans and other-than humans, with blatant disregard for the embodied knowledge these ecosystems cultivate and nourish…”19 An economy that privileges wellbeing benefits its citizens’ quality of life through education, access to mental and physical healthcare, and, among other benefits, a balanced environment.

Considering climate change as central to perpetuating inequitable social, racial, and economic systems and the COVID-19 pandemic is an essential aspect of the ecologies of care rooted in historical structures of discrimination. Cultural critic Janine Francois states that

we can think about climate change as a very contemporary phenomenon or we can locate it via colonialism. We can then locate the same relationship to Covid-19, in how bodies of Colour in the Global South and North are disproportionately affected by a disease due to discriminatory systemic practices. These two issues are not separate, they are connected in how Black, Brown and Indigenous bodies marked by gender, class and sexuality and other indicators of underprivilege are affected by our lack of access to resources and care. Covid-19 is a climate issue. I come back to the question of how do we create ‘ecologies of care’. How do we work against structures, systems, institutions, policies, laws and practices that affect so many of us who are oppressed and marginalised? How do we create our own systems of care founded on resistance and futurity, that operate beyond the limitations of capitalism?20

Monsters are the symbol of imbalance as discussed in the introduction. They take up a lot of space, play on our deepest fears, and are the antithesis of how we characterize ourselves. In a world where balance is prioritized, a sense of the other is as meaningful as a sense of self. To create balanced ecosystems we cannot simply stop polluting Hann Bay or erecting palm oil plantations in place of rainforest: we must change our cities, our farms, our reliance on certain kinds of energy, and how we source those.

Carson explores environmental destruction through the use of insecticides where farming done on scale creates an imbalance of nature that has to be controlled. When there is no diversification of agriculture, then populations of damaging insects become imbalanced. To manage this, insecticides are used, often at the clear physical expense of those who work on and near farms.21 Carson brought unprecedented attention to the damage pesticides cause to humans and their environment, and was instrumental in the ban on the use of Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and other insecticides. What her study on the long-term effects of chemicals highlights is how systemic toxins can also be weaponized. There is a long history of murdering communities through the use of poison gases. The use of systemics has most recently been released by the Assad regime in Syria to catastrophic ends. The way in which the human destruction of the environment is connected to corruption and human rights violations is undeniable.

Ultimately, the conversation around environmental destruction today cannot be examined through one lens—through the loss of a species’ habitat or polluted water or corporate greed—because it is connected to our very existence. We must be able to speak of all of these things, the causes, effects, and corruption around which the climate crisis circulates. The allure of the grotesque and monstrous forms of Monteiro, Khan & Selesnick, and Esslinger make it hard to look away—they are canaries amplifying alarm. In the same way, once we begin to remove the layers that have built up around protecting those who profit from environmental destruction and climate change, it is impossible to ignore the urgent need for change.

Notes

-

Paul Shepard, “The Place of Nature in Man’s World,” Atlantic Naturalist 13 (April-June 1958): 85-89. ↩︎

-

Theodore R. Schatzki, The Site of the Social: A Philosophical Account of the Constitution of Social Life and Change (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2002), 149. ↩︎

-

Angus Galloway, conversation with author, May 14, 2021. ↩︎

-

Yinka Shonibare, interview for Earth Kids, produced by James Cohan, a film by Greg Poole, 2020, https://www.jamescohan.com/artists/yinka-shonibare-cbe/videos?view=slider, accessed February 1, 2021. ↩︎

-

Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2016), 9. ↩︎

-

Ghosh, The Great Derangement, 27. ↩︎

-

Just as imagining the true impact of COVID-19. Greg Dalton, “Killer Combination: Climate, Health, and Poverty,” Climate One, February 12, 2021, https://www.climateone.org/audio/killer-combination-climate-health-and-poverty, accessed February 12, 2021. ↩︎

-

Jori Lewis, “Cleaning Up Muddy Waters: The Fight to Revive Senegal’s Hann Bay,” Environmental Health Perspectives 124, no. 5 (May 2016): A93. ↩︎

-

J.T. Houghton, L.G. Meira Filho, B.A. Callander, N. Harris, A. Kattenberg, and K. Maskell, Climate Change 1995: The Science of Climate Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 439. See also pages xi, 4-5, and 39. ↩︎

-

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002), 6-7. ↩︎

-

Ghosh, The Great Derangement, 11. ↩︎

-

Nicholas Stern, The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review, HM Treasury of the UK Government, October 2006, vi. ↩︎

-

“Free market travellers” was coined by Naomi Klein in “How Power Profits from Disaster,” The Guardian, July 6, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jul/06/naomi-klein-how-power-profits-from-disaster. ↩︎

-

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, “Pliny the Elder and Man’s Unnatural History,” Greece & Rome 37, No. 1 (April 1990): 81. ↩︎

-

Wallace-Hadrill, “Pliny the Elder and Man’s Unnatural History,” 83. ↩︎

-

Wallace-Hadrill, “Pliny the Elder and Man’s Unnatural History,” 86. ↩︎

-

Dalton, “Killer Combination.” ↩︎

-

Dalton, “Killer Combination.” ↩︎

-

Ecologies of Care: Screening and conversation with Silvia Federici and Angela Anderson https://www.e-flux.com/live/284380/ecologies-of-care-screening-and-conversation-with-silvia-federici-and-angela-anderson/ (accessed April 23, 2021). ↩︎

-

Janine Francois, “Ecologies of Care,” Journal of Visual Culture & Harun Farocki Institut 34, https://www.harun-farocki-institut.org/en/2020/07/07/ecologies-of-care-journal-of-visual-culture-hafi-34-2. ↩︎

-

Carson, Silent Spring, 30-33. ↩︎