Nathan Jackson, Tlingit

Nathan Jackson (b 1938) is a revered Tlingit artist of the Sockeye clan on the Raven side of the Chilkoot Tlingit, widely recognized as one of the most important Alaska Native artists of his generation. Based in Ketchikan, Alaska, Jackson has spent decades shaping the field of Northwest Coast Indigenous art through his masterful totem poles, cultural stewardship, and exceptional command of formline. He formally studied art and deepened his practice at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. Since then, he has created more than 50 monumental totem poles, as well as canoes, carved doors, masks, jewelry, and clan crest panels, all grounded in the elegant geometry and flowing rhythm of formline—a highly sophisticated system and visual language central to the identity and storytelling of many PNW Nations. Formline is based on ovoids, U-forms, and interconnecting shapes to create complex visual narratives. As a formline artist, Jackson is renowned for his ability to translate ancestral narratives into bold, expressive compositions that honor tradition while remaining distinctly his own. His work demonstrates unparalleled fluency in visual storytelling, often conveying complex themes of kinship, transformation, humor, and spiritual presence. Jackson’s carvings are not only technically masterful but also deeply rooted in his community’s cosmology and social structure, reflecting the protocols and ceremonial functions of Tlingit art. Jackson’s legacy includes works held in major collections and cultural landmarks, such as the National Museum of the American Indian, the Field Museum, Harvard University’s Peabody Museum, and the Alaska Native Heritage Center. He has also left his mark on public sites across Alaska, from Juneau to Saxman to Totem Bight State Park. A lifelong mentor and tradition bearer, Jackson plays a central role in training the next generation of carvers and artists, offering workshops and demonstrations throughout the Pacific Northwest. His contributions have earned him some of the highest honors in American arts, including the National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts (1995), the Rasmuson Foundation Distinguished Artist Award (2009), and recognition as a United States Artists Fellow (2021). He also received an honorary doctorate from the University of Alaska Southeast and was commemorated on the U.S. Postal Service’s Raven Dance stamp in 1996. In 2022, Jackson and his son, artist Jackson Polys, were invited by Sealaska Heritage Institute to create poles for the Totem Pole Trail in Juneau, reinforcing their intergenerational commitment to cultural sovereignty through art.

Judas Ullulaq, Inuk (Canada)

Judas Ullulaq (b 1937–d 9 January 1999) was a profoundly influential Inuk artist from Talurjuaq (Taloyoak) in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut, later residing in Uqsuqtuuq (Gjoa Haven). Renowned for his dynamic, mixed-media sculptures that blend emotion, movement, and spirituality, Ullulaq was also a beloved community leader, remembered for his warmth, gentleness, and humor. His work is central to the recognition of Kitikmeot artists as pioneers in expressing Inuit cosmologies through sculpture.

Ullulaq came from a powerful family of artists—his brothers Nelson Takkiruq and Charlie Ugyuk, and his nephew Karoo Ashevak, were all celebrated carvers. Together, their work forged a distinct visual language marked by surreal energy and supernatural themes. He was one of the first in his region to incorporate whalebone, as well as soapstone, ivory, antler, muskox horn, and sinew, into his sculptural compositions, producing figures that were both fearsome and humorous.

His creative journey began in childhood, when he observed his mother and sisters sewing, and learned to make dolls. He also hunted with his father and brothers, a lived experience that deeply informed his later carvings of hunters, animals, and daily Arctic life. He began sculpting ivory miniatures in 1961, evolving into larger, expressive mixed-media sculptures that became hallmarks of his style. Ullulaq’s sculptures are widely recognized for their wild expressiveness. The figures gesticulate broadly, gaping mouths, bulging inlaid eyes, flared nostrils, and animated gestures that bring spiritual and traditional Inuit stories to life. Though best known for exploring supernatural realms, Ullulaq often balanced those themes with humor and depictions of everyday moments, such as cleaning fish or dog sledding, blending the mythic with the mundane in a uniquely compelling way. His first solo exhibition took place in 1983, and by the mid-1980s, his work had begun to appear regularly in national and international galleries. Over his lifetime, he participated in over 90 solo and group exhibitions, and his work is held in major collections including the National Gallery of Canada, the Canadian Museum of History, the Winnipeg Art Gallery, the Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, and the Dennos Museum Center in Michigan, among others.

Sáandlaanaay/Kimberly Fulton Orozco

Sáandlaanaay/Kimberly Fulton Orozco is an artist and storyteller whose work explores the intergenerational impacts of assimilation and the complex forces that shape identity. Her practice reflects on themes such as the fragmentation of memory, the transmission of knowledge through relationships, loss of language, and the renewal of belonging.

A Kaigani Haida Raven from the Yaahkw’ Jaanaas clan of Craig, Alaska, Kimberly was given the name Sáandlaanaay, meaning “first sunrise,” which is drawn from a Haida origin story. She is a citizen of the Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska.

Born in Ridgecrest, California, Kimberly was raised between two cultural worlds, situated halfway between her maternal homeland of Jalisco, Mexico, and her paternal homeland of Craig, Alaska. Her art reflects this blend of cultural inheritances, often incorporating traditional Haida forms while reinterpreting them through abstraction. Through her work, Kimberly engages with the tension of being a multicultural Indigenous person in a rapidly changing world, exploring how identity shifts and evolves across time and space.

Kimberly received her BFA in Drawing, Painting, and Printmaking from Georgia State University in 2022, and she is currently pursuing an MFA in Studio Arts at the Institute of American Indian Arts. Her work has been exhibited at institutions such as the Anchorage Museum and the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, and her writing has been featured in Smithsonian Magazine. In 2023, she was honored to be selected as one of the first Indigenous artists for the U.S. Mint’s Artistic Infusion Program.

Kimberly’s work is rooted in a deep sense of gratitude and connection to her ancestors, and she is committed to continuing the practice of cultural exploration and renewal through art.

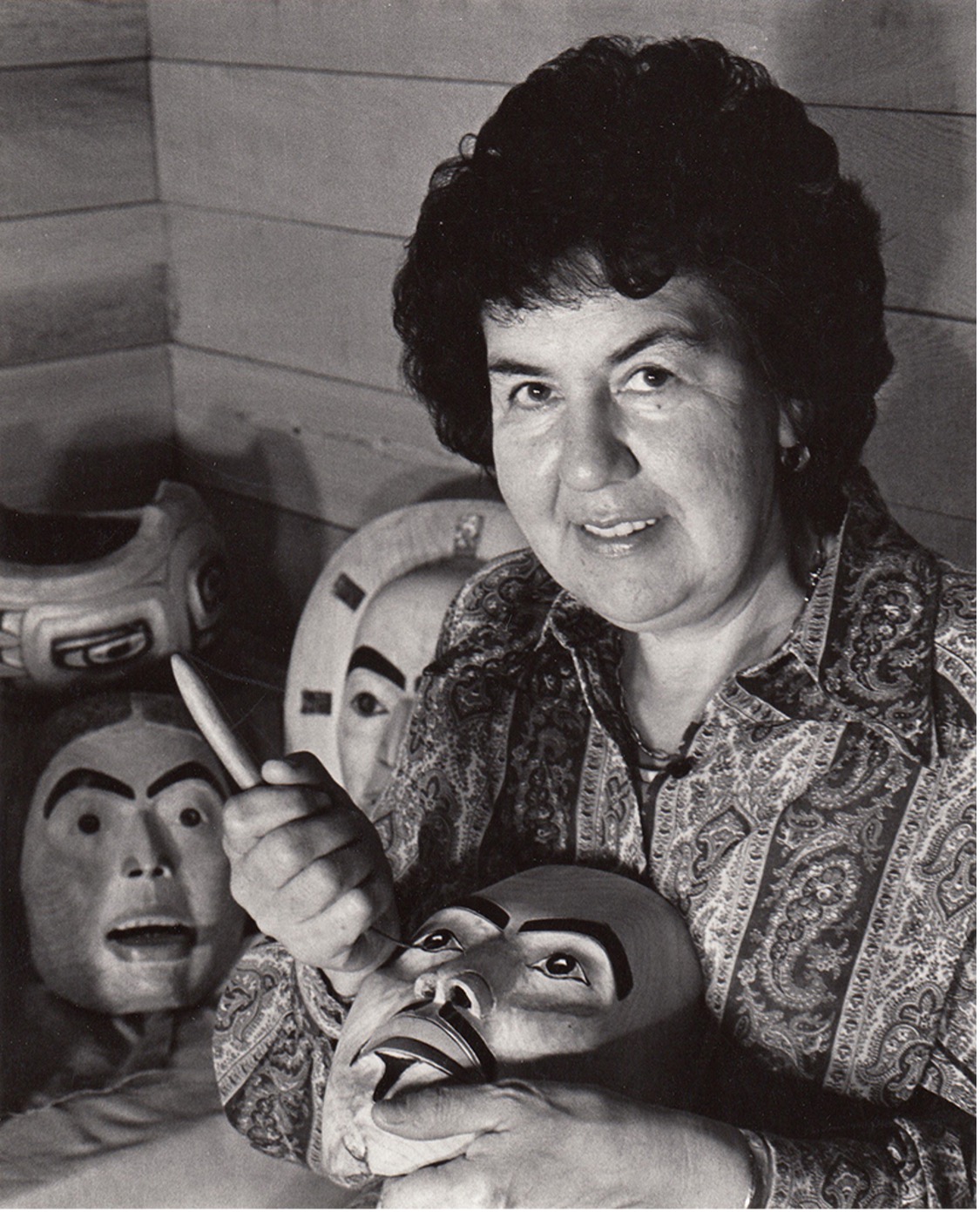

Freda Diesing

Freda Diesing (b 2 June 1925–d 4 December 2002), of the Sadsugohilanes Clan of the Haida Nation, was a trailblazing artist whose mastery of formline carving and unyielding commitment to cultural resurgence helped ignite the Northwest Coast art revival of the late 20th century. She was one of the very few women of her generation to carve totem poles.

Born Marie Alfreda Johnson in Prince Rupert, British Columbia, she came to carving later in life, beginning her formal practice at age 42. She had earlier studied painting at the Vancouver School of Art. Still, her creative path sharpened when she became one of the first students at the Gitanmaax School of Northwest Coast Indian Art (‘Ksan) in Gitksan territory. There, she honed her skills under the mentorship of master artists Tony Hunt (Kwakwaka’wakw) and Robert Davidson (Haida), as well as art historian Bill Holm, grounding her in the principles of formline design and traditional Haida carving.

Working across mediums, Diesing carved portrait masks, bowls, wall panels, and monumental poles. Her work radiates a deep respect for Haida aesthetics and ancestral knowledge, blending traditional teachings with an independent, fiercely contemporary spirit. She was responsible for totem poles raised in the Tsimshian community of Kitsumkalum, for the RCMP station in Terrace, and for several public installations in Prince Rupert, including commissions for hospitals and community centers. Her button blankets and carved wall panels reveal her fluency in both ceremonial and public art practices.

Throughout her life, Diesing was not only a prolific maker but also an influential teacher. From her home in Terrace, B.C., she mentored some of the most prominent Northwest Coast artists of the next generation, including Dempsey Bob, Norman Tait, and her nephew Don Yeomans. She taught widely across the Pacific Northwest and beyond, including residencies in the Dominican Republic and symposia in Finland, carrying the language of Haida carving onto the global stage.

Her artistic excellence and cultural leadership were recognized shortly before she died in 2002, when she was awarded the National Aboriginal Achievement Award and an honorary doctorate from the University of Northern British Columbia. In 2006, her legacy was permanently honored with the creation of the Freda Diesing School of Northwest Coast Art in Terrace, British Columbia. This institution continues to shape a new generation of Indigenous artists, rooted in tradition and innovation.

Denise Wallace, Sugpiaq (Alutiiq)

Denise Wallace (b 1957), a Sugpiaq (Alutiiq) artist, has redefined the boundaries of Native American jewelry through her intricate, storytelling adornments. Renowned for her mechanical ingenuity and transformative motifs, Wallace fuses ancient Sugpiaq narratives with contemporary forms, crafting works that open, move, and reveal—much like the ancestral stories that inspire them. Born in Seattle, Wallace spent formative years in Alaska, reconnecting with her cultural roots through her grandmother’s influence. She trained in lapidary and silversmithing before enrolling at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe at the age of 19, where she earned her AA in Fine Arts in 1981. Santa Fe became her creative home for two decades, where she and her late husband and collaborator, Samuel Wallace, ran a successful studio and gallery. Their partnership yielded an unprecedented body of work that elevated Wallace’s jewelry to global acclaim. In 1999, the couple moved to Hawai‘i’s Big Island, where their collaborative practice continued until Samuel’s passing in 2010. Today, Wallace’s legacy remains deeply familial—her son David Wallace serves as her primary lapidary artist, and she shares studio space with her daughter, Dawn Wallace Kulberg.

Wallace’s jewelry—crafted from silver, gold, fossil ivory, coral, semi-precious stones, and scrimshawed walrus and mammoth tusk—features moving parts such as hinges, doors, and latches. These intricate mechanisms echo Sugpiaq and broader Arctic traditions, particularly ceremonial masks that open to reveal hidden spirits. Her art, she explains, explores “the transformation of the inner spirit of an animal, person, or object,” and this theme of transformation is the lifeblood of her work. Her creations are wearable epics: faces, figures, textiles, and beings from Native Alaskan cosmologies that animate the surfaces of belts, pendants, and earrings. Wallace’s practice is steeped in themes of healing, identity, nature, and cultural continuity, informed not only by her heritage but also by the legacy of Indigenous artists such as Allan Houser, Charles Loloma, John Hoover, and Roxanne Swentzell. Wallace’s work has been celebrated in major museum exhibitions including Arctic Transformations: The Jewelry of Denise and Samuel Wallace (Anchorage Museum and Smithsonian NMAI), Gifts of the Spirit (Peabody Essex Museum), and the PBS series Craft in America. Her pieces are held in the permanent collections of the Anchorage Museum, the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, and the Mingei International Museum in San Diego.

Richard E. Baker, Squamish and Kwakwaka’wakw

Richard E. Baker (b 12 February 1962–d 25 November 2024) was a celebrated Squamish and Kwakwaka’wakw artist whose carvings and metalwork embodied the strength, beauty, and living traditions of his peoples. Rooted in ancestral knowledge and shaped by lifelong practice, Baker’s art spanned the mediums of cedar and precious metals, affirming his status as a master carver and jeweler with an international following.

Born on the Capilano Indian Reserve in North Vancouver, British Columbia, Baker grew up surrounded by art. His maternal grandmother, the revered Katherine Scow, was part of a long line of Kwakwaka’wakw artists, and from a young age, he was immersed in the creative traditions of his family. At just 12 years old, Baker began carving under the guidance of his father and other community carvers, crafting his first pieces from cedar, the lifeblood of Northwest Coast material culture.

For decades, Baker honed his skills in wood carving, and was known for totem poles, masks, and commissions that blended tradition with personal innovation. Later, he turned to metalwork, bringing the same precision to gold, silver, copper, and platinum.

Baker’s work was featured in exhibitions and major commissions across Canada, including invitations to carve in Toronto, Montreal, and at Expo 1986 in Vancouver. His pieces were frequently commissioned by corporations and First Nations organizations, reflecting the deep trust placed in him as a cultural ambassador.

A dedicated mentor and community leader, Baker supported emerging artists and championed cultural continuity through collaborative efforts. He was especially proud of his three sons, all of whom inherited his creative spirit and carried forward the legacy of Squamish and Kwakwaka’wakw artistry.

Bill Reid, Haida

Bill Reid (1920–1998) was a celebrated Haida artist, master goldsmith, sculptor, writer, and cultural advocate whose work profoundly shaped the resurgence and global recognition of Northwest Coast Indigenous art in the 20th century. Throughout his fifty-year career, Reid produced more than a thousand original pieces spanning jewelry, sculpture, screen printing, and painting, establishing himself as one of the most influential Indigenous artists of his time. Born William Ronald Reid Jr. on January 12, 1920, in Victoria, British Columbia, he was the son of Sophie Gladstone, a Haida woman of the Raven/Wolf clan from T’aanuu Llnagaay, and William Ronald Reid Sr., an American of Scottish-German descent. Although his mother attended residential school and did not initially pass on her Haida heritage, Reid reconnected with his ancestral roots in his twenties during a formative visit to his mother’s home village of Skidegate. This journey toward cultural reclamation became the cornerstone of his life’s work. In Skidegate, Reid studied with his maternal grandfather, Charles Gladstone, a traditional Haida silversmith and descendant of the legendary artist Charles Edenshaw. From Gladstone, Reid not only learned foundational techniques but also inherited Edenshaw’s carving tools—symbolically linking him to a revered artistic lineage. This mentorship inspired Reid to begin creating Haida-inspired jewelry and to study the deeper symbolic language of Haida formline design, much of which had been disrupted by colonial policies and cultural suppression. After studying jewelry at the Ryerson Institute of Technology in Toronto while working as a CBC radio announcer, Reid returned to the West Coast and opened a studio on Vancouver’s Granville Island. Over time, he moved from finely detailed jewelry to monumental public sculptures that blended traditional Haida stories and forms with modernist approaches and materials. Working in gold, silver, argillite, red cedar, bronze, and Nootka cypress, Reid developed a distinctive aesthetic that reinterpreted Haida mythology for contemporary audiences. His major public works include The Spirit of Haida Gwaii (in both black and jade versions, installed at the Canadian Embassy in Washington, D.C., and Vancouver International Airport, respectively), Chief of the Undersea World (a breaching orca at the Vancouver Aquarium), and Raven and the First Men (a monumental red cedar carving depicting a foundational Haida creation story, housed at the University of British Columbia’s Museum of Anthropology). These works were not only artistic triumphs but cultural landmarks that introduced Haida cosmology and aesthetics to an international audience. Reid was also a writer, broadcaster, and mentor who played a pivotal role in advocating for the recognition of Indigenous art as a legitimate form of fine art. In 1975, he engaged in a published dialogue with art historian Bill Holm, titled Form and Freedom: A Dialogue on Northwest Coast Indian Art, which helped frame Northwest Coast art as both traditional and evolving. In addition to his artistic achievements, Reid was deeply committed to cultural and environmental justice. In the 1980s, he paused work on The Spirit of Haida Gwaii to protest the clear-cut logging of Haida Gwaii’s ancient forests. His activism contributed to the creation of Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, affirming his role not just as an artist, but also as a protector of his ancestral lands. Reid received numerous honors during his lifetime, including honorary degrees from six Canadian universities, the National Aboriginal Achievement Award for Lifetime Achievement, and membership in the Order of British Columbia, the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, and France’s Order of Arts and Letters. His work was featured on Canada’s $20 bill from 2004 to 2012 and commemorated in stamps and coins. In 2008, the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art was established in Vancouver to celebrate his legacy and promote contemporary Indigenous artists of the region. He lived with Parkinson’s disease for many years and passed away in Vancouver on March 13, 1998. His ashes were returned to T’aanuu Llnagaay by canoe—a final journey that echoed the spirit of his work and life. Bill Reid’s Haida names—Iljuuwas (“Princely One”), Kihlguulins (“One Who Speaks Well”), and Yaahl SG̱waansing (“The Only Raven”)—reflect his multifaceted contributions as an artist, thinker, and cultural emissary. Through a life devoted to rediscovery, creation, and advocacy, Reid helped revive and reimagine Haida visual culture for future generations, forever transforming the landscape of Indigenous art in Canada and beyond.