This small sculpture, carved in India sometime during the 11th-12th centuries, depicts Avalokiteśvara , the bodhisattva of compassion.

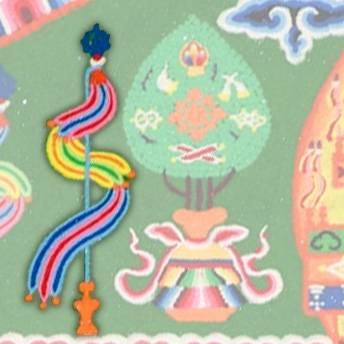

What is a bodhisattva? In some Buddhist traditions, specific qualities or character traits to be cultivated by followers are expressed in human form as divine beings known as bodhisattvas. Giving a human form to an abstract quality allows Buddhists to imagine themselves emulating or becoming like the bodhisattva, cultivating within themselves the qualities embodied in the deity. There are many bodhisattvas — Manjushri is the bodhisattva of wisdom. Maitreya is the bodhisattva of benevolence or kindness.

Avalokiteśvara is the bodhisattva who embodies the quality of compassion—the ability to understand the suffering of others. Known as the “one who listens to the cries of the world,” Avalokiteśvara is motivated by a keen desire to help alleviate the suffering of all.

Select highlighted areas of the sculpture to learn more.

One story demonstrates the intensity of Avalokiteśvara’s desire to help others along the path to enlightenment. Long ago, Avalokiteśvara made a vow never to rest until he had freed all beings from samsara, promising that if he ever gave up, his head should split into a thousand pieces. One day, observing the intense suffering in the world, he became discouraged and decided that it was not possible to help so many, that instead he should work only for his own benefit. At that moment his head split into a thousand pieces. When he realized what had happened, he called out to Amitabha Buddha for help. Amitabha Buddha used his great power to reassemble the pieces of Avalokiteśvara’s head, and also gave him a thousand arms so that he could be of help to ever more beings. Amitabha Buddha put an eye into the palm of each of the thousand hands, so that Avalokiteśvara’s compassion for others would always be informed by wisdom. What does this story tell us about becoming discouraged? Seeking help? Becoming stronger?

The Sanskrit word samsara means “journeying” and in Buddhism is the name for the repetitive cycle of birth, death, and rebirth caused by attachment and desire.

A sculpture like this one would have been used to as a visual aid to meditation, a practice of controlling one’s thoughts and breath in order to train the mind. A person might focus on the image and meditate on the compassion embodied by Avalokiteśvara, as well as on his dedication to helping others on the path to enlightenment. While meditating, one might recite the Sanksrit mantra associated with Avalokiteśvara, Om Mani Padme Hum .

There are many ways to interpret this mantra. Here is one. The syllable Om indicates one’s intention to cultivate compassion in body, speech, and mind — known in Buddhism as the three “doors” by which one enters the world. Mani means “jewel” and represents compassion itself. Padme means “lotus” and symbolizes wisdom. Without wisdom, compassion can be well-meaning but misguided. Hum symbolizes one’s intention to cultivate wisdom and compassion together.

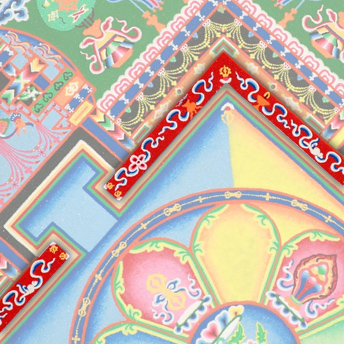

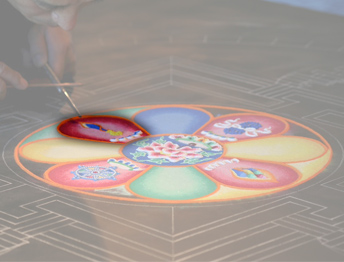

Another form of meditation on the compassion of Avalokiteśvara which has been practiced by Buddhist monks for centuries is the making of a sand mandala.

Avalokiteśvara is sometimes called the "one who works tirelessly

to help all of those who call his name." Because Avalokiteśvara’s

compassion calls him to help others, his pose is one of action.

Compare his pose to that of Buddha in a sculpture from the same

era.

Avalokiteśvara is sometimes called the "one who works tirelessly

to help all of those who call his name." Because Avalokiteśvara’s

compassion calls him to help others, his pose is one of action.

Compare his pose to that of Buddha in a sculpture from the same

era.