In the current fashion for Victoriana we may confidently expect a revival of public interest in these darlings of Victorian taste which also fascinated an artist like Whistler.

—R A. Higgins, 1962

Just as the nineteenth century was tiring of the perfect poise of Classical Greek sculpture, the spade of a Boeotian laborer hit upon a new inspiration. Scores of ancient figurines were unearthed from fields surrounding the ancient city of Tanagra, humble objects made of clay, often bearing traces of painted decoration, and rarely more than nine inches tall. The statuettes were ancient, dating to the late fourth and third centuries BCE, but to the Victorians, they were new. “Their principal charm,” observed the antiquarian Frederic Vors in 1879, “consists in the fact that they are completely different from any other antiques we know.”1 Unburdened by inscriptions, allusions, or religious significance (as far as anyone could tell), the figurines seemed to be intended only to delight. Here, at last, were antiquities for everyone, ancient objects that could be appreciated without the benefit of a classical education. “The remarkable side of the matter is this,” wrote Marcus B. Huish in 1898, “that no one with instincts for beauty, or interest in antiquity, or in the evolution of art can fail to be at once captivated by these terra-cottas.”2

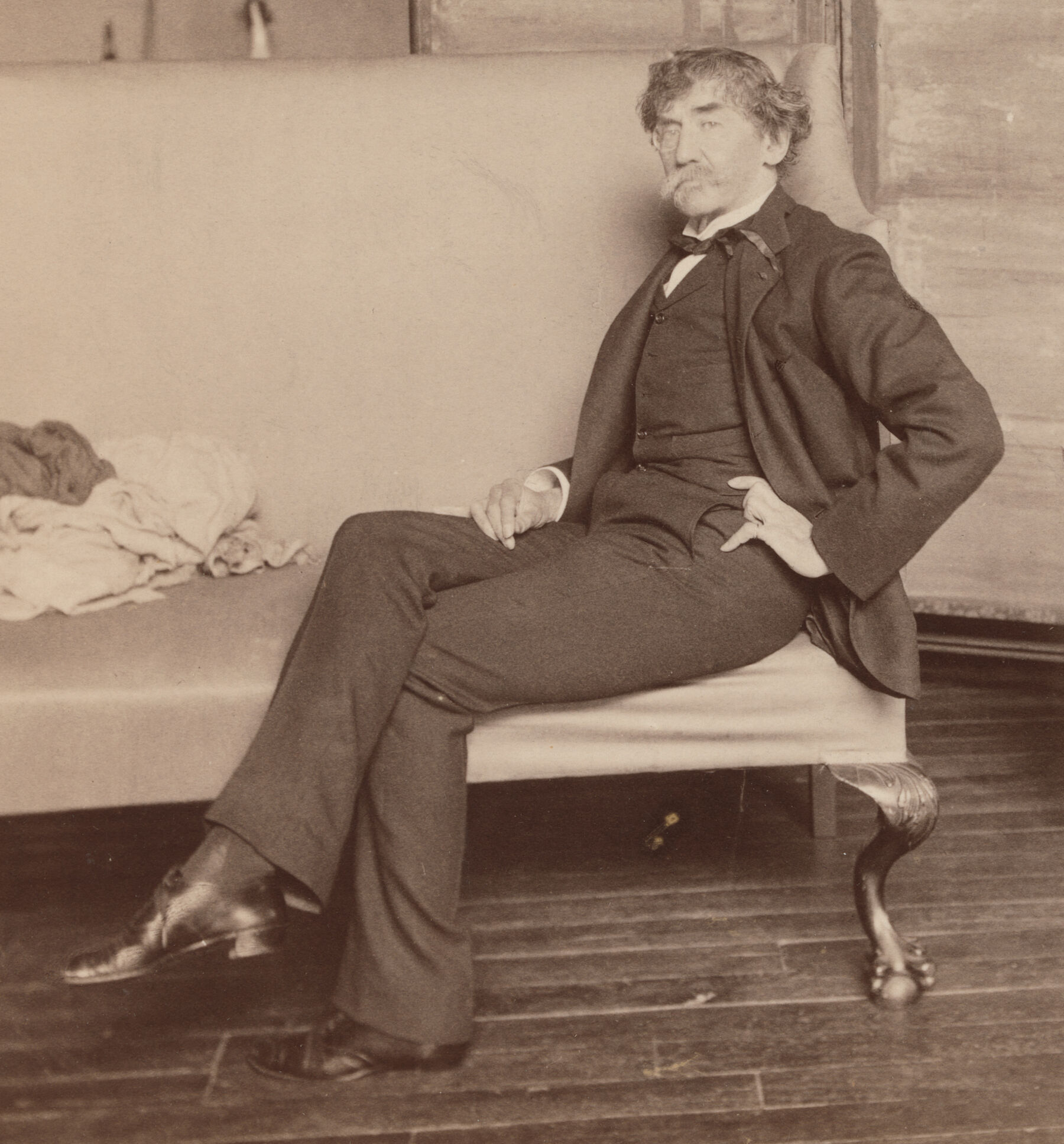

As the Louvre historian Néguine Mathieux has remarked, “The figurines appeared during an age that ardently yearned for them.”3 Recasting Antiquity: Whistler, Tanagra, & the Female Form explores this episode in the history of taste. The Tanagras, diminutively scaled, delicately tinted, and physically fragile, were instantly adorable to collectors and connoisseurs, exciting both “the covetousness of museums” and “the sagacity of archaeologists.”4 Moreover, they were confidently predicted to benefit the art of their own time: “These terra cottas,” pronounced Charles de Kay, “are object lessons in art which we cannot afford to be without.”5 Among the leading artists to fall under their spell was James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) (fig. 1.1), the American expatriate painter, printmaker, and designer best known for the poignant portrait of his aging mother. Between 1887 and 1896, at the peak of his professional life, Whistler created images of classically nude and lightly draped figures that reveal his fascination with the ancient figurines. The lithographs in particular, impressions of delicate drawings printed in ink on paper, have come to be called “Tanagras” for their air of grace and gaiety, the very qualities that made the ancient terracottas such treasured objects in the decades surrounding the turn of the twentieth century.

Figure 1.1: Detail, Paul François Arnold Cardon, called Dornac (French, 1859–1941). Photograph of Whistler in his studio on the rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, Paris, 1893. Sheet: 7 3/4 x 10 1/4 in. (19.7 x 26 cm), mount: 35.6 x 43.2 cm (14 x 17 in.). Yale Center for British Art. Gift of Robert N. Whittemore, Yale BS 1943. Image: Public domain via CC 0 1.0 Universal.

The dainty little ladies from Tanagra

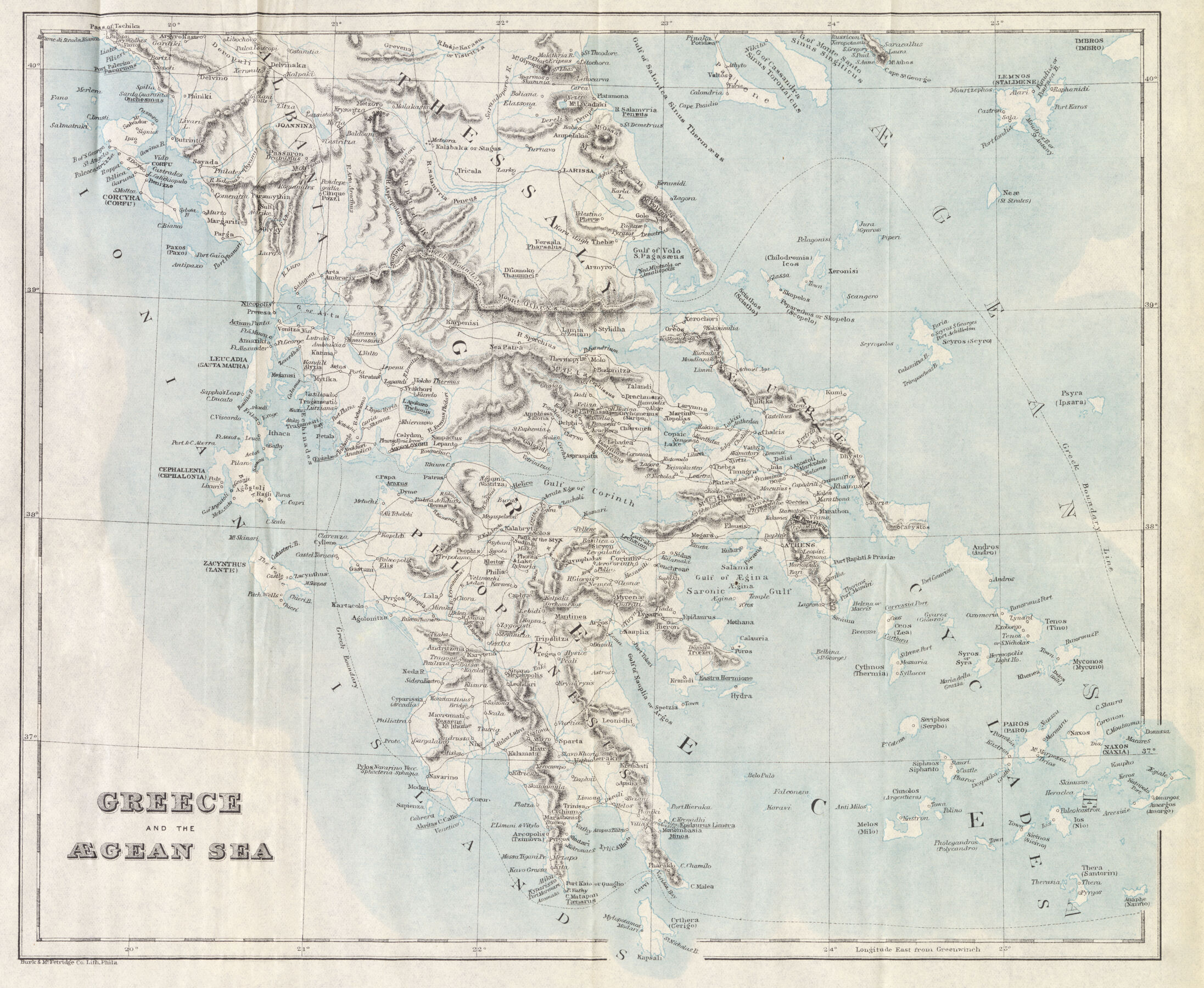

“To ninety-nine people out of a hundred,” wrote C. A. Hutton in 1899, “the interest in any collection of Greek statuettes centres in the dainty little ladies from Tanagra.”6 Although terracotta statuettes were manufactured and distributed throughout the Hellenistic world, the findings at Tanagra around 1870 were so extraordinary and unexpected that the name of the site became indelibly attached to the entire class of female terracotta figurines. Tanagra lies sixty miles north of Athens, not far from Thebes, in the region of Boeotia (fig. 1.2), “a name as readily misspelt,” Huish observed, “as ill-pronounced” (Bee-OH-shee-a). According to Reynold Higgins, a modern-day authority on Tanagra terracottas, Boeotia was “a by-word in antiquity for clumsiness and stupidity,” and Huish and his contemporaries could hardly believe that so gauche a place could engender so much charm.7 In fact, the format and technology had originated in fourth-century Athens, with figurines exported to Boeotia, where the style was adopted and then perfected by local craftspeople. By the third century BCE, Tanagra productions were disseminated throughout, and even beyond, the Greek world.

Figure 1.2: “Greece and the Ægean Sea,” from Rambles and Studies in Greece by J. P. Mahaffy (1839–1919). Philadelphia: Henry T. Coates & Co., 1900.

The figurines that particularly appealed to nineteenth-century collectors were made in the early Hellenistic era, between 330 and 200 BCE. Although their subjects range from women and children to actors and old men, the dominant type by far is the standing female figure draped in fabric that falls to her feet and usually enfolds her hands. These female statuettes were “much prettier” and more carefully executed than the others, according to the French archaeologist Olivier Rayet (1847–1887), who supposed they had been assigned to the most skilled of the mold-makers.8 In keeping with the fashion of the day, the typical Tanagra figure wears a large mantle, or cloak, called a himation—“de rigeur when a Greek lady walked abroad,” one Victorian writer imagined—over a finely pleated tunic called a chiton (fig. 1.3). In a variation on the earlier, Classical style of draping figures, the thinly woven himation is pulled tightly across the body, showing the folds of the heavier garment underneath.9

Figure 1.3: Draped woman, Boeotian, 3rd century BCE. Terracotta, H: 19.6 cm (7 3/4 in.). New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Rogers Fund, 1907, 07.286.2. Image: Public domain courtesy of the Met’s Open Access Policy.

The hair of a typical Tanagra figure is intricately styled (fig. 1.4)—one elaborate coiffure has been named by modern art historians for a cantaloupe (see cat. no. 3)—and sometimes covered by a kerchief, or a veil thrown over the head like a hood, or a straw sunhat called a tholia. The figure occasionally holds a heart-shaped fan, or a mirror, or even a child, and usually strikes a self-assured pose, “as if attentive to a speaker or an object of not over-exciting interest.”10 Her facial expression is generally impassive, which to the Victorians signaled a welcome absence of “dark passions”: “Search through the entire known list of Tanagra ceramics,” wrote Mary Curtis in 1879, “and you will not find a note discordant with the expression of peace, gladness, sportiveness, tempered with a mood of pleased attention, or repose.”11

Figure 1.4: Figurine, Boeotian, ca. 300–250 BCE. Terracotta, H: 24 cm. London, British Museum, 1874.0305.65. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

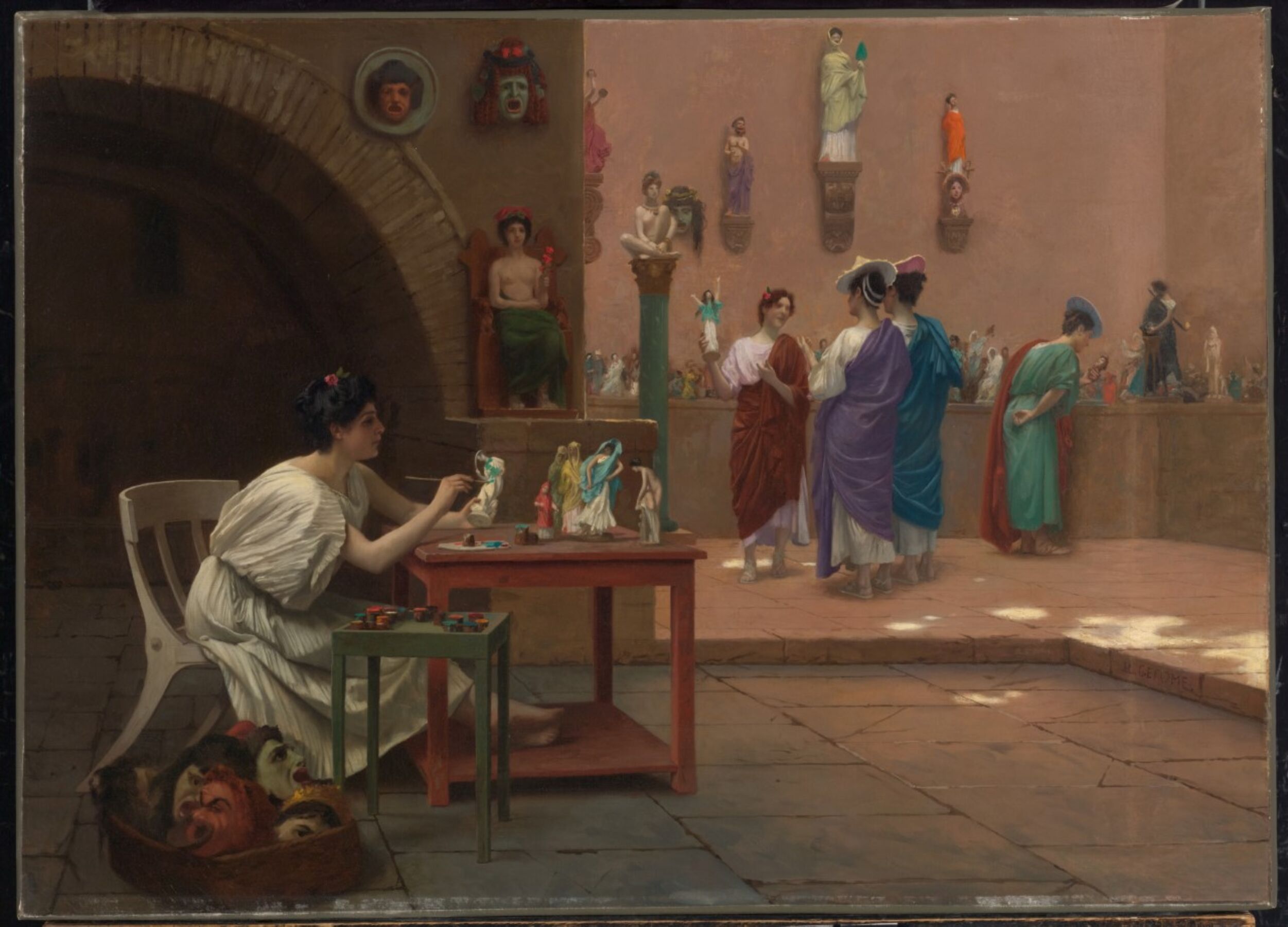

The artisans who created these quiescent figurines were known as coroplasts, the Greek word for “modelers of girls,” sometimes contemptuously construed as “makers of dolls.”12 The scorn attaches not only to the domestic subject matter but also to the medium (what Huish called “common mother earth”),13 which lacked the prestige of marble or bronze. Nevertheless, nineteenth-century writers generally esteemed the craftsmen as “artists,” or at least “potters,” and naturally assumed them to be male: “All these little figures,” writes Wilhelm Fröhner, a Louvre curator, in 1888, “are of exceptional beauty, created by men of genius.”14 The painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, on the other hand, envisioned the coroplast as a young woman in Antique Pottery Painter: Sculpturae Vitam insufflat pictura (“Painting breathes life into sculpture”), an image of a terracotta workshop painted in 1893 (fig. 1.5). Gérôme’s artisan is dressed in a plain white chiton of the sort worn by enslaved servants in ancient Athens,15 though it might also be the artist’s conception of an ancient artist’s smock, or simply a means of distinguishing her workaday clothing from the brilliantly tinted drapery of the statuettes she makes in multiplicity.

Figure 1.5: Jean-Léon Gérôme (French, 1824–1904). The Antique Pottery Painter: Sculpturae vitam insufflat pictura (Painting breathes life into sculpture), 1893. Oil on canvas, 50.1 x 68.8 cm$$ (19 3/4 x 27 1/16 in.). Art Gallery of Ontario, Canada. Gift from the Junior Women’s Committee Fund, 1969 (69/31). Image © AGO.

The production of a Tanagra figurine began with a prototype, a statuette usually modeled by the artist in wax or terracotta. Most Victorian writers presumed that these were modeled from life in the fashion of modern sculpture, as “miniatures of living men and women.”16 “They are so human in their dainty prettiness,” wrote Hutton, “that we realize at once that their type of beauty is not the ideal one of the sculptor, but the real one of every-day life.” A writer for the Art Journal went so far as to imagine the Greek artist catching sight on the street of the “elastic step and swaying robes” of one of the graceful women of Tanagra, “who undoubtedly served as models,”17 thereby transposing to antiquity the myth of the Pre-Raphaelite “stunner,” a woman of such astonishing beauty that the artist must persuade her to pose or die from disappointment.

It remains an open question whether the prototypes were in fact modeled from life. Olivier Rayet could not believe that the Tanagras were mere “reductions of grand sculpture,” when they seemed so well adapted to the terracotta medium and so comfortable in their diminutive proportions,18 yet modern scholarship suggests that they were probably based on life-size statuary, or archetypes, such as the so-called Large Herculaneum Woman (see fig. 2.2), made by leading sculptors. The prototypes, however, were not simply copies in miniature but adaptations, which elevated them “to a high plane of creativity,” as the art historian Malcolm Bell III remarks.19 As a writer for Scribner’s Magazine acknowledged in 1881, the coroplast was “no mere mechanic, no ordinary potter, repeating impressions from the matrix given to him, but an artist, with the soul of a sculptor.”20

To create a mold, the prototype would be coated with wet clay.21 Once it dried to a pliable consistency, the clay would be removed to make a concave template, retouched by hand. In one exceptionally fine surviving example (cat. no. 2), we can see how the inner surface has been treated with a modeling tool to emphasize the fine lines of the drapery’s pleated folds, the dominant aesthetic aspect of the figurines. Finished in a kiln, a furnace for firing pottery, the mold became the matrix in which the figurine would be shaped.

To make a figurine, moist clay would be impressed into the mold in a thin, even layer; as it dried, the lining would shrink slightly and release from the mold, whereupon the coroplast would again work by hand to correct blemishes and enhance details. “While the clay was soft,” the Art Journal related, “either with a few bold, flat strokes of some tool the ampler folds were made, or more elaborate effects were brought about by an infinity of lines, which reproduced the foldings and purflings of the himation.”22 This intervention of the coropolast’s hand, sometimes marked with a fingerprint (see fig. 2.6),23 brought the object “to a degree of perfection,” as Fröhner observed, “which a merely mechanical process is unable to give.”24 This was a crucial point, for the Victorians needed to distinguish the Tanagras, as mass-produced works of art, from the modern gewgaws daily disgorged by factories in industrial towns in the north of England.

The earliest terracottas in Boeotia were produced from a single mold, with a simple slab in back, but around 330 BCE the two-piece mold became customary in Tanagra workshops. Thereafter, most Tanagra terracottas were sculptures in the round.25 Separate molds were made for parts that would be added to the bodies—solid heads, which proved to be almost indestructible;26 accessories like fans, hats, and floral wreaths; and projecting features such as arms and, occasionally, legs or wings. Whether cast from molds or modeled by hand, those parts would be attached to the figurine’s body with the creamy mixture of clay and water called slip, also used to smooth the joins between connecting elements. The hollow figurines would then be settled onto a rectangular plaque, or plinth, and vented in the back to allow moisture to escape and forestall explosions.27 The statuettes emerged from the oven as terracottas, a term that means “baked clay” and refers to fired-clay objects modeled by hand or mass-produced with the use of molds.28

Unlike painted Greek vases, their “sister art” in clay,29 which underwent a complex, three-phase firing process, the figurines were fired only once, at a temperature lower than was required to create an impermeable pot. The potter and the coroplast both relied on the kiln, and may even have shared facilities, but because a terracotta figurine would never be used like a krater or a kylix, it could be simply painted after firing with water-soluble pigments. The figurine was prepared for pigmentation with a coat of whitish clay called kaolinite—a “bath of whitewash,” in Victorian parlance—applied “to overcome the porous nature of the clay” and provide a smooth ground for color. It could be seen “wherever the colour has disappeared.”30 The full polychromy—colors applied to ancient pottery, sculpture, or architecture—would survive for only a generation or two. Over centuries of burial, the pigments inevitably crumbled or dissolved (see cat. no. 5), and according to nineteenth-century accounts sometimes faded as soon as the objects were exposed to the air.31 Nevertheless, from what remains we can gather, as Gérôme does in The Antique Pottery Painter, how vibrantly, even garishly colored the statuettes must originally have been.

According to Fröhner, much of the Tanagras’ popular appeal derived from their “delicate flesh tint,” a warm roseate shade that, for Victorian connoisseurs, may have recalled the complexion of an English rose. (Oscar Wilde describes a character in An Ideal Husband, 1895, as “really like a Tanagra statuette,” “a perfect example of the English type of prettiness, the apple-blossom type.”)32 The typical Tanagra was adorned with blue eyes, rouged cheeks, vermilion lips, black eyebrows, and reddish-brown, or hennaed, hair. Although her shoes were usually hidden beneath her drapery, those that could be seen had red soles, like the Christian Louboutin designer items of our own time: those striking soles are named as an element of the standard Tanagra costume in Le Costume Historique (1888) (see cat. no. 51), which adds the information that the shoes themselves were yellow, making them resemble, Rayet reflected, the Turkish slippers of the nineteenth century.33

The painters lavished their artistry on the figure’s garments, highlighting their importance as markers of status and sophistication.34 Popular shades were violet and mauve, pigments obtained from the rose-madder plant, although the drapery might be painted almost any color, as Henri Houssay observed in 1876, in “the whole range of soft shades and broken tones familiar to the painters of Pompeii.”35 We can see this clearly in another of Gérôme’s works, Atelier de Tanagra (“Tanagra Workshop”) (fig. 1.6), whose plummy palette was apparently inspired by that of the figurines. The artist envisions the brilliant violet, scarlet, and turquoise hues of drapery worn by both the figurines and their consumers, while the coroplast, another woman in white, is portrayed touching up a Tanagra figurine with color. Not pictured here is the final, extravagant step for the most precious figurines, the application of gold leaf to details such as fibulae (brooches), earrings, diadems, or the edging of a cloak, gilding designed to catch the light as it glanced across the curves, braids, and folds of the female figure.36

Figure 1.6: Jean-Léon Gérôme (French, 1824–1904), Atelier de Tanagra (Tanagra workshop), 1893. Oil on canvas, 64.4 x 91.1 cm (25 1/4 x 35 3/4 in.). Private collection. Image Courtesy of Sotheby's, 19th Century European Art, Sotheby’s Sale N09034, Lot 67, November 8, 2013.

Just by tilting the head or turning an arm or adding a hat or an ivy wreath, a coroplast could produce a variety of figurines from a single mold, creating endless variations on a theme. Although each was individually conceived, all possessed “l’air de famille,” as Houssay remarked—a family resemblance. A second generation would arise when existing mold-made figurines were used as prototypes to yield new molds, thus creating extended families, or “iconographic groups,” in which the figurines might differ in size, due to shrinkage in the kiln, but remain consistent in style, attitude, and accessories. As the archaeologist Edmond Pottier famously phrased it, “All the Tanagra figures are sisters, but few of them are twins.”37

A new light on Greek sculpture

Frederic Vors assumed, perhaps reflexively, that the Tanagras had been “rather looked down on by the more æsthetic Athenians,”38 a condescending attitude that has not altogether disappeared. Over time, the prototype’s progeny—the mold-made terracottas—moved away from the perfection of the archetype. As the aloof manner of the Classical was tempered with the local color of Tanagra, the figurines exhibited their own idiosyncrasies and flair. It was precisely these departures from convention that proved so endearing to Victorian audiences. “They are summary, sketchy, suggestive,” as Scribner’s described them, “often thrown into disproportion by the shrinkage of the kiln, or by a chance pressure of the potter’s hand. For perfection they have no care.” Hutton insisted that their “sketchiness” was only “the suppression of the unimportant,” and the Art Journal defended their defects as evidence of what the French called l’art bon-enfant, or good-natured art.39 Particularly in comparison to the severe, marmoreal splendor of the Parthenon sculpture in the British Museum, the terracottas of Tanagra offered agreeable interpretations of antiquity, eliciting affection rather than awe. “An entirely new light was thrown on Greek sculpture by the discovery of the Tanagra figurines,” affirmed the American novelist Rupert Hughes in 1896. “It robbed Hellenic art of its last claim to frigid austerity, and credited it rather with the intimate appeal and the warmth of humanity that were always the acme of its endeavor.”40

The new light also reflected on the polychromy of the terracotta figurines, which came as a delightful surprise to the nineteenth century. For one thing, it helped resolve a longstanding scholarly debate: because of their colorful aspect, the New York Times asserted in 1890, “the question of painting statuary has been settled, in so far that we can be sure the ancients colored most, if not all, of their statues.”41 Even ancient descriptions of colorful statuary could be dismissed without extant works to back them up, but the recently unearthed figurines could not be ignored, even by the “chromophobes.”42 The Times critic, as it happens, was writing in reference to Gérôme’s figuration of modern archaeology titled Tanagra (see fig. 4.8), a sculpture that featured several partial representations of terracotta figurines cast in the muted palette of the nineteenth century, as though they had just been pried loose by the archaeologist. Those figurines served Gérôme’s allegory as material evidence supporting the existence of polychromy in ancient marble sculpture, instantiated by the painter in the monumental nude figure.

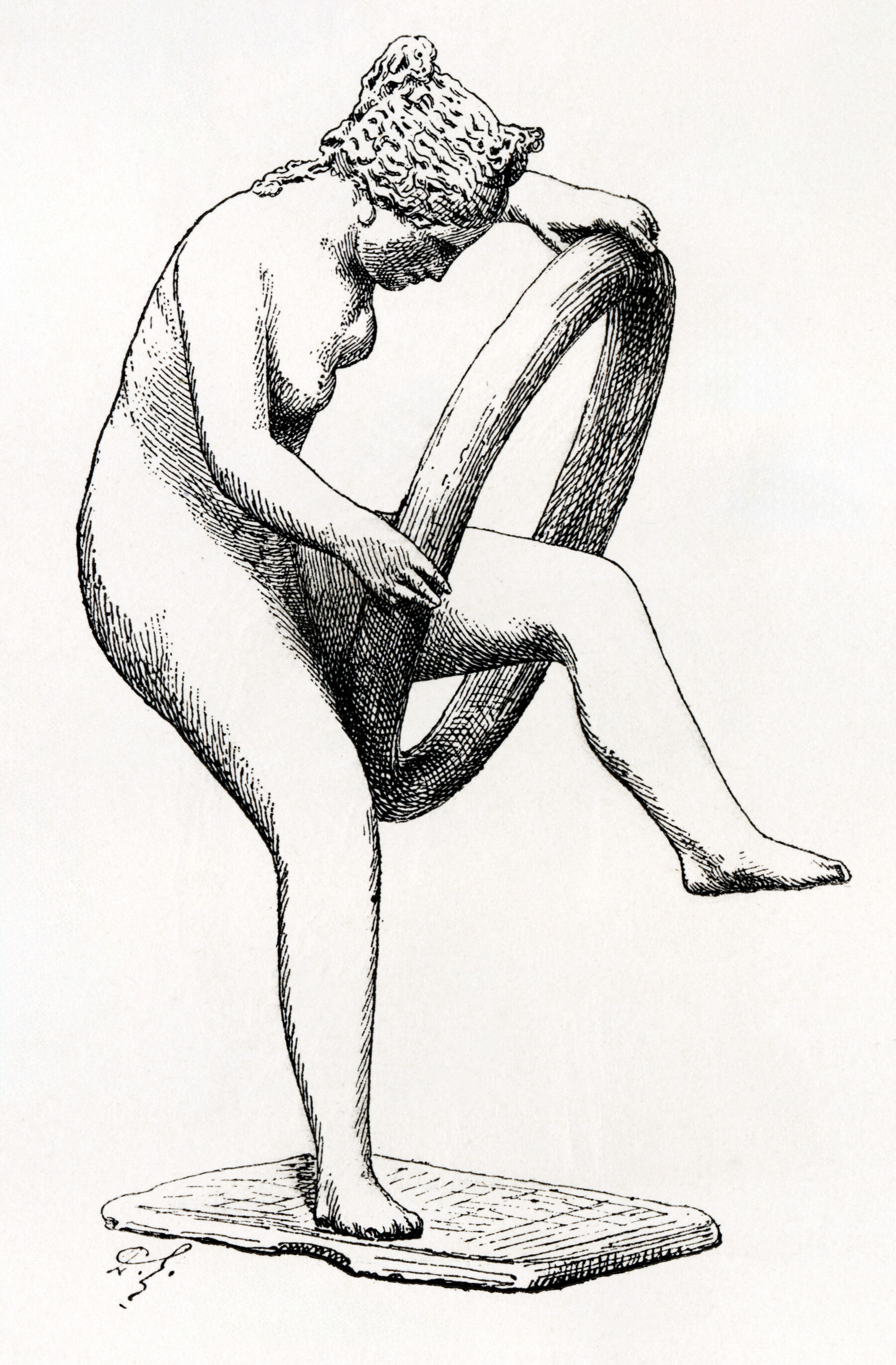

Moreover, as Brigitte Bourgeois observes, the polychromy of Tanagra figurines had a positive aesthetic and commercial effect: “It contributed to the impression of life emanating from the clay figurines, and encouraged the late nineteenth-century bourgeoisie in their dreams and craving for an ‘imaginary antiquity.’” More than any other factor, color allowed the figurines to seem “familiar and intimate,” examples, as the Athenaeum said, “of what we should now style popular art.”43 This made it difficult to know how to categorize them. Rayet attempted to force the “popular” antiquities into the canon by illustrating them among “the most remarkable specimens of the antique world” in Monuments de l’Art Antique (cat. no. 52).44 They look out of place there, among such icons of antiquity as the Borghese Gladiator and the Crouching Venus, and might better be regarded, as the American Architect and Building News suggested in 1879, as “the genre of classical sculpture.”45 Although certain antiquaries objected to the use of an expression borrowed from modern art,46 “genre” was a convenient term for classifying imagery that was unusual for its very ordinariness, “portraits of the people in their daily life, as they passed it,” as Marcus Huish described them, “seated in their houses, or pacing the streets in the bright sunshine.”47

Scribner’s cast the terracottas in a different metaphorical frame, referring to them as “the every-day report, the journalism, of Greek life.”48 Some scholars persisted in looking for deities and legendary heroes among the figurines, but it was generally agreed that they were “merely idealized figures from daily life.”49 In time, the relentless refrain of Tanagras as representations of “ordinary life” and “ordinary costume” became a measure of their monotony, and “when a fairly large series is seen together,” they were regarded as “wearisome.”50 Their interpretive possibilities were quickly depleted: unlike the comparatively arcane imagery on Greek vases, for example, about which a scholar might intone for pages, Tanagras did not require any special erudition to understand or vocabulary to explain. As one critic noted of an 1888 exhibition, “the very remarkable collection of ‘Tanagra’ figures will appeal to the less ‘cultured’ amateurs of Greek ceramics.”51

Perhaps as a corollary of their lesser position in the hierarchy of art, many of the scholars who studied the terracottas were female, at least in England. In 1891, when a Miss Sellers gave a lecture on the figurines at the British Museum, the Illustrated London News was moved to remark that “the learned ladies sent forth from Girton and Newnham,” the women’s colleges founded at Cambridge in 1869 and 1871, had done much to revive interest in classical art. Moreover, it was “incontestable” that they had helped “to popularize the fruits of recent discoveries among men and women of all classes,” which is to say that they were particularly adept at promoting Tanagras among the uneducated.52

One of the “learned ladies” from Girton was C. A. (Caroline Amy) Hutton, born in New Zealand, who used her initials professionally to avoid being marked as female and thereby regarded as an amateur—despite her honors degree in Classics and a commendation of her “classical learning and artistic discrimination” from the estimable A. S. Murray, keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum, in the preface he penned for her Greek Terracotta Statuettes of 1889.53 Ten years earlier, Mary F. Curtis’s name had not even been imprinted on the title page of Tanagra Figurines, although “Miss Curtis” was acknowledged as its author in a book review.54 In 1900, Marcus Huish glibly ignored the hard work of his predecessors, excusing his own uncredentialed entry into the field with the assertion that until the publication of his book, the only available resource in English had been a chapter in Murray’s Handbook of Greek Archaeology.55

If even accomplished Victorians could be rendered invisible by their gender, it is little wonder that women in the nineteenth century found pleasure and took pride in the Tanagra figurines, images of female autonomy and self-possession. “Life in Greece was lived by men,” announced one writer for Harper’s Bazaar, referring to the silence in classical literature on the daily lives of women, which made it seem as though half the human race had lived for centuries in seclusion. Here, with the Tanagras, were “representations by which we might remake in our fancy the ways of life belonging to women in general.” Indeed, as Hutton reflected, quoting an epigram by Agathias, “Why do more than half the Tanagra ladies wear hat and shawl if ‘they were not allowed to breathe the outer air, and brooding on their own dull thoughts, must stay within?’”56

Une joyeuse société

In the nineteenth century, the “object or intention” of the Tanagra figurines remained a matter of conjecture. John Pentland Mahaffy, professor of ancient history at Trinity College Dublin, cautioned that it was “necessary to suspend our judgment, and wait for further and closer investigation,” though he himself was inclined to adopt the theory that the statuettes were made as children’s toys rather than fine art, if only because the “minor” artisans who made them were called dollmakers and “held in contempt by real sculptors.”57 Evidence from Athenian tombstones appears to confirm Mahaffy’s theory, though we now generally accept that the figurines possessed “functional flexibility”— that they were used in different ways at different times for different reasons.58 With a single object, “the house was ornamented, the god was honoured, and the dead comforted.”59

The primary purpose of the figurines from Tanagra was probably funerary, however, as the majority were found in the necropolis, or cemetery. Yet unlike lekythoi, vessels made specifically for “sepulchral purposes” and frequently decorated with funereal themes, the Tanagra terracottas had nothing of the mortuary about them.60 “With what intention,” wondered Rayet in 1875, “was this multitude of figurines put in the burials?”61 Hutton pointed out that “the use of gay colors and cheerful images in connection with the grave is singularly in contradiction with modern views of death,” and she could only reconcile the incongruity with the view that in ancient Greece, the dead “cheered the dark passage with images of kind and beautiful companions, and with symbols of vigor, of sentiment, of action, and of mirth.”62 Perhaps because the figurines were regarded with such affection in the nineteenth century, this view of the Tanagras as companions even into death gained currency. Mahaffy thought the terracottas might attest to the human inclination to bury beloved objects with a friend “that he might not feel lonely in his gaunt and gloomy grave,” and Vors imagined them enlivening the grave, which the Greeks associated with immobility, by providing a “jolly little crowd of little people—all full of action and life,” perhaps representing the deceased’s kith and kin. To Rayet, the gathering was “une Joyeuse société,” a joyful company made up of graceful women and laughing children.63

Reluctant to associate Tanagras with the tomb, the Victorians were even more unwilling to relate them to religion. “Some have argued that being found in tombs they must have a religious intention,” the American Architect reported, summarizing the state of the field, “but the majority have come to reject this theory and accept them rather as intended simply for ornaments.”64 Archaeological evidence from Tarentum, a site in Italy, contradicts that interpretation of Tanagras as “profane images which bore no relationship to the sacred,”65 and even in the nineteenth century, commentators sought to strike a compromise between the two positions: the terracottas ended up as grave gifts or votive offerings but only after enjoying a secular existence as beloved household objects.66 A. S. Murray, in a rare feat of imagination, pictured the figurines “swept together from the walls when some important individual of the house died.”67

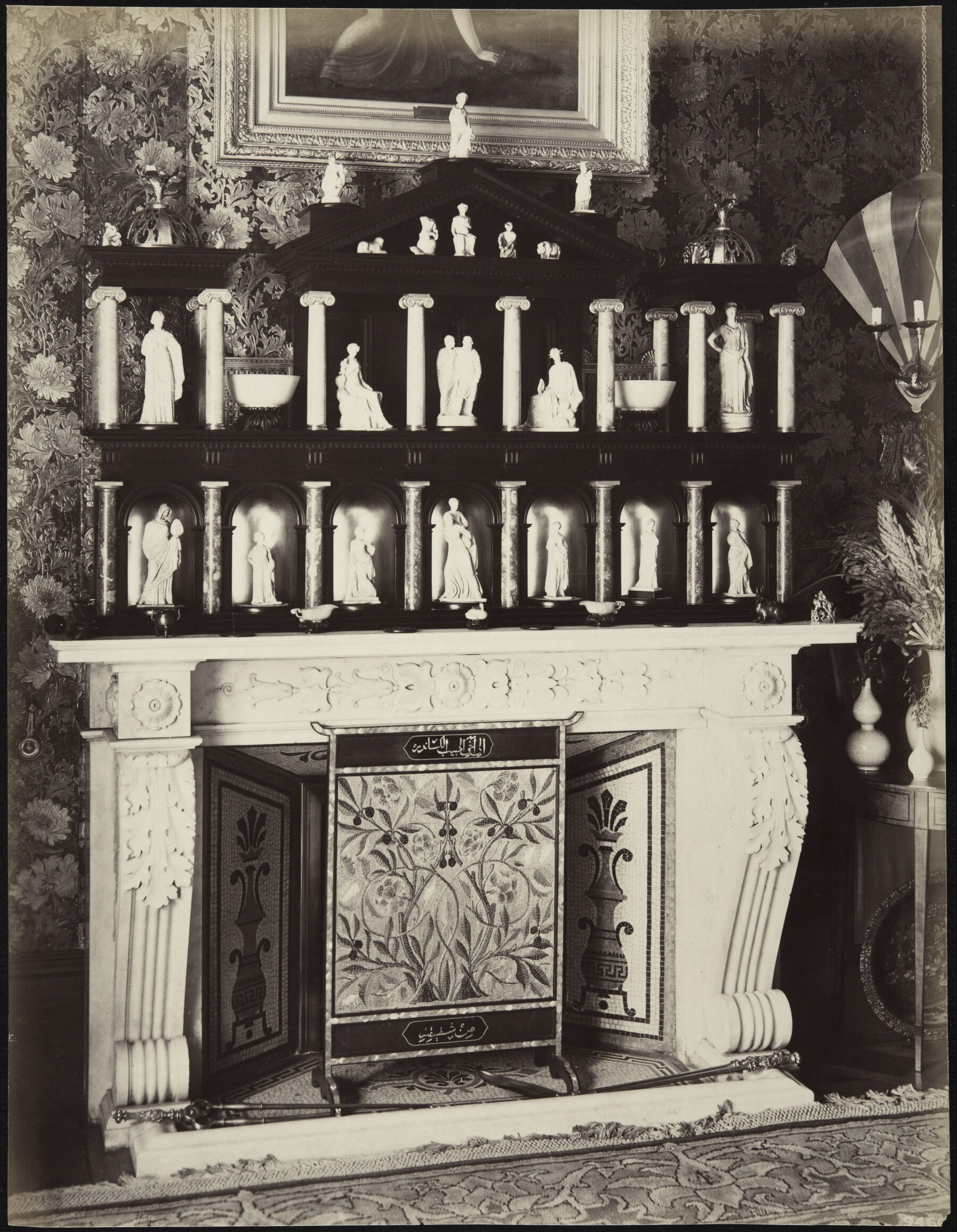

Figure 1.7: The fireplace in the antiquities room at No. 1 Holland Park, London, with the Ionides Collection of Tanagra figurines. Photograph (albumen print) by Bedford Lemere & Co., 1889. Swindon, Historic England Archive, BL09466. Image © Historic England Archive.

Even into the Roman period, the terracottas were intended to decorate private houses,68 “to stand on shelf or in niche if not to be suspended on a peg,” as Charles de Kay supposed: they were “the familiars of the family without attaining to the dignity of household gods or portraits of ancestors.”69 Nineteenth-century commentators took delight in regarding them as ancient knickknacks, objets d’art made to crowd curio cabinets and mantelpieces in overdecorated houses (see fig. 1.7). Although coming from a period “of far higher artistic attainment,” the terracottas could readily be related to contemporary collectibles made by “the ordinary Italian or French modeler . . . working in haste for a popular market”—or, from the American point of view, “those gaudy figurines that are sold in Europe to-day at country fairs.”70 Predominantly female, the terracottas were most frequently compared to Meissen porcelain figurines, “the China ‘shepherdesses’ of modern ware” (fig. 1.8). Such analogies enhanced the Tanagras’ popularity as accessible antiquities while undermining their stature and significance as works of art. Murray, whose job was to acquire antiquities for the British Museum, haughtily remarked that “the koroplathos of Tanagra must have worked for a market where there was less intelligence than what is called taste, and when the wants of private houses were studied rather than the public sense of true beauty.”71

Figure 1.8: Figure of a Shepherdess, Meissen (Meissen Porcelain Factory, 1710–present), ca. 1770. Hard-paste porcelain with enamel and gilt decoration, 26.3 x 10.8 x 11.4 cm (10 3/8 x 4 1/4 x 4 1/2 in.). Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Bloomfield Moore Collection, 1882. Image © Public domain.

Jean-Lèon Gérôme better understood the “wants of private houses” and the desires of common consumers. His Antique Pottery Painter (see fig. 1.5) reflects a contemporary conception of a coroplast’s studio, with an array of “real” and imagined terracottas ranged on the shelves, adjacent to a boutique that would not have looked foreign to nineteenth-century shoppers (although the customers eerily epitomize the figurines they purchase). The cleverness of Gérôme’s conceit becomes apparent when we recognize that the objects lined up on the workbench are anachronisms, images of the artist’s own invention titled Hoop Dancer (cat. no. 44). The figurine derives from the prototype held aloft by Gérôme’s marble Tanagra (see fig. 4.8) and may have been inspired by an unusual (and fraudulent) terracotta of a nude acrobat shown at the 1878 Exposition Universelle (fig. 1.9).72 Those pictured on the canvas, five awaiting polychromy to order, replicate the artist’s own pastiche of a supposedly ancient archetype, making the painting a riddle of reproductions and originals, forgeries and authentic works of art. The Antique Pottery Painter further functions as a high-art advertisement of the mass-produced figurines, which Gérôme offered in plaster and gilt bronze, commodities that just might be affordable to those for whom an actual Tanagra, to say nothing of an original Gérôme, would have been an impossible luxury.

Figure 1.9: Jongleuse (Juggler), “Terre cuite de la collection de M. Lécuyer” (Terracotta from the collection of M. Lécuyer). Reproduced in Olivier Rayet, “Exposition Universelle. L’Art Grec au Trocadéro,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, series 2, 18, no. 1 (1878): 359.

The secret of their charm

With their tasteful swathes of drapery, the Tanagras may have served in their time as three-dimensional fashion plates.73 From studying a figurine, one could learn how a Greek woman dressed, “the shape, colour and fashion of her different garments, and . . . with what infinite variety she arranged a costume which, in itself, is extremely simple, and whose elements never varied.”74 A color plate in Auguste Racinet’s encyclopedic Le Costume historique illustrates “Indoor and Urban Costume, exactly as worn, here by Tanagran women” (cat. no. 51)—the “Tanagran women” being Tanagra figurines, works of art so true to life that they were considered to provide faithful depictions of “the actual costume of their period.” Hutton regarded their realism to be “the secret of their charm.”75

If only Victorian women would dress as well, sighed the Saturday Review in 1876, if only they, too, wore clothing that “followed the lines of the form, instead of distorting them—if graceful drapery were the first object aimed at—there would no longer be questionings as to long waists or short waists, crinolines, stays or straps.” If examples of such elegant costume were not to be found in the fashion magazines of Paris, then English ladies might avail themselves of a visit to the British Museum, where they could study “the exquisite draperies of the little Tanagra terracottas, the most beautiful fashion models we shall ever see.”76

It was impractical to suppose that modern women could survive in antique drapery, whatever its aesthetic quality, but it was also naïve to imagine that the sumptuous clothing of the Tanagra figurines, so consciously and skillfully manipulated, could ever have been their everyday attire. The volume and complexity of the drapery would have made it difficult for women to use their hands for much beyond grasping the edges of the himation, and they would have had to move at a slow, deliberate pace to manage the voluminous folds of material and avoid disturbing the disposition of the dress. “Given these impracticalities,” Rosemary Barrow observes, “it is unlikely that multiple layers of fine drapery were in everyday use.”77

Contrary, therefore, to the Victorian point of view, the figurines did not portray ordinary people fitted out in casual clothing for everyday activities. They reflected not reality, but an ideal. Because drapery is neither cut nor tailored, “the beauty of the chiton and himation lay in the art of positioning them around the body,” as Barrow notes, which implies a certain level of sophistication to wear them well; the figurines, therefore, may have modeled the way a perfectly well-dressed, well-informed Greek woman presented herself in public. Such women would have been members of the social elite who dressed up in finery for special occasions—religious ceremonies or festivals where they would have been expected to display the family’s wealth and civic-mindedness.78 Another of their purposes, then, as Sheila Dillon has argued, may have been to commemorate women’s participation in religious rituals: collectively, the figurines can be seen to represent “the world of women on the public stage.”79 The implicit paradox of the figurines—images of women parading their social status with ostentatious clothing, elegant coiffures, and red-soled shoes while maintaining the modest demeanor of well-bred ladies—would not have been lost on Victorian women of the upper classes.

If “the dainty little ladies of Tanagra” were elite, they were nonetheless mortal, lacking the attributes that would identify them as goddesses. Yet there were among the terracottas depictions of the popular goddess Aphrodite, perhaps because she held particular relevance for maidens and married women. As Daniel Graepler notes of the Hellenic worldview, “The borderline between the human world and the mythical sphere of the gods is often tenuous.”80 For the Greeks, the archetypical Aphrodite was the Knidia (fig. 1.10), the masterpiece by Praxiteles and the first life-size cult statue of the goddess fully in the nude—a sculpture that created, all at once, the ideal of female physical beauty.81 Terracotta Aphrodites sometimes allude to their illustrious predecessor with their old-fashioned hairstyles, loosely gathered in the back and with a center part; but what makes them immediately recognizable—“évident au premier coup d’œil” (“evident at first glance”), as Rayet writes in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts—is their partially draped condition.82 (Were they to be entirely “undraped,” as Curtis points out, the figurines would be “less steady on their legs.”)83 In one common type (cat. no. 10), perhaps adapted from a portrait statue of Phryne, the courtesan of Praxiteles, Aphrodite strikes a pose relaxed enough to hold for an eternity: her left hand rests lightly on her swaying hip, her right on a pedestal, her legs crossed casually underneath her skirt.84 If her facial expression looks stern for the goddess of sexual love, the seduction resides in her swaggering pose, with the drapery slipping far enough to bare her breasts but still conceal her modesty.

Figure 1.10: The Ludovisi Venus, a Roman copy of the Knidian Aphrodite, Praxiteles, ca. 360–330 BCE, Marble, H: 205 cm (81 in.). Image: Public domain.

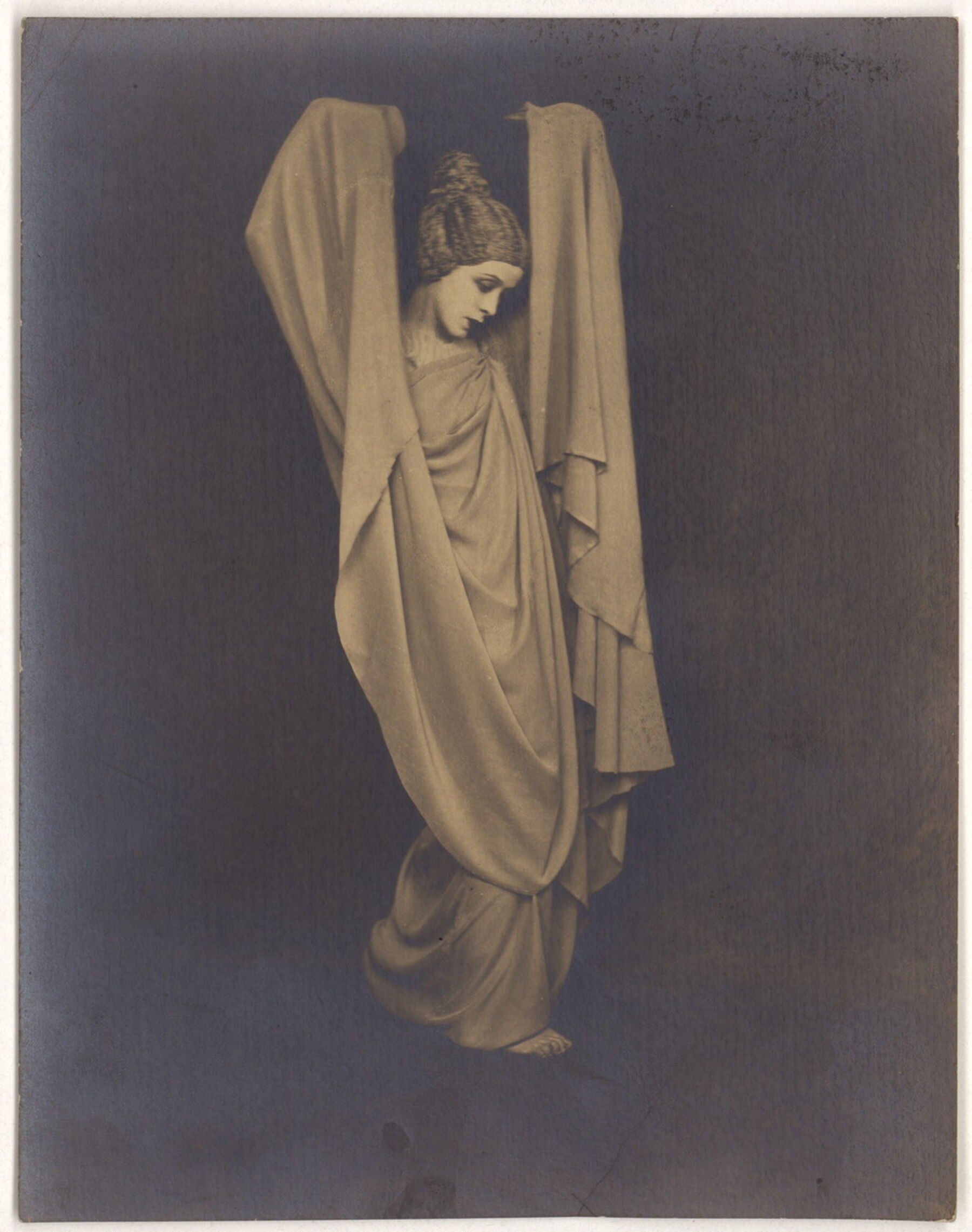

Another goddess occasionally found among the Hellenistic terracottas is Nike, the winged Victory. “They really do appear to fly,” Lucilla Burn remarks, “their tall, beautifully feathered wings extended, one leg pushing free of the drapery, which then presses back in windswept folds against the other leg and body.” Because of the projecting wings, the Nike statuettes were especially fragile and may have been intended especially for the grave, perhaps to signify the spirit’s escape from its confines.85

Nikes became a specialty of the workshops at Myrina, a settlement in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey near the town of Izmir, formerly Smryna) that was probably established by emigrant Boeotians who brought their molds and models with them. Edmond Pottier excavated the site in 1881 and four years later, when the terracottas were exhibited in Paris, they were appreciated as “at once a complement and a contrast to the lovely sepulchral terra-cottas of Tanagra.”86 Indeed, the Myrina figurines not only supply the gods and heroes absent from the Tanagra population but also manifest a more complex polychromy, with colors layered or artfully juxtaposed to enhance their luminosity (see cat. no. 6).87 The Myrina figurines are further distinguished by their remarkable “expression and energy,” as the Illustrated London News observed, a departure from the “dignified repose” of their Tanagra cousins.88

In olive woods round Tanagra

In one romantic origin story, the ancient artisan makes his Tanagra terracottas of such “deathless grace and charm” that they are fated to become the “playthings to his dead.” Buried by their maker “in the tombs of his elders on the hillsides of Bœotia and elsewhere,” they sleep peacefully, undisturbed for centuries “until the pick of the archæologist and the excavator on the yellow hillsides by Tanagra wakened them to a new day and brought them forth.”89 In reality, the unearthing efforts in Boeotia were heedless and rapacious, an unfortunate episode in the history of art and archaeology. The graverobbers so completely destroyed the archaeological context—the evidence of the figurines’ arrangement in the tombs—that even today, these objects remain in many ways a mystery.

Olivier Rayet, who was resident in Athens when the terracottas first turned up, pieced together the story of the early “excavations.” As a collector himself—a potential customer—Rayet was able to communicate with the tomb robbers and learn from them directly what was happening to the burial grounds around Tanagra; as an archaeologist, he could make sense of the situation and record his conclusions for the readers of the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1875 (cat. no. 49).90 Graverobbing was not new to the Tanagra region, but it was only in 1870, when some inhabitants of a village three miles below Tanagra called Schimatari (“the place of statuettes”) began exploring the earth beneath the vineyards covering a nearby hill, that some curious little objects turned up.91 Word of the finds reached a professional excavator (or graverobber) from Corfu named Yorghos Anyphantès, known as Barba-Georghis (Uncle George). By December he had set to work, finding that the ancient graves lined the roads leading out of town, which allowed him to excavate the territory with extraordinary efficiency.92

The assiduity of Uncle George inspired scores of laborers from surrounding villages, who helped him ransack the neighborhood. They dug day and night to the utter neglect of the region’s agriculture,93 plundering some ten thousand graves between 1872 and 1874. Nearly half the tombs yielded nothing of interest, but some of those in the dry, white clay of the hillside contained figurines that were largely intact, with much of their original painted decoration.94 As Murray points out, it was “from want of supervision at the beginning, and perhaps in defiance of it since,” that the illicitly obtained terracottas poured into private hands and even museum collections, including the Louvre, which made its first accessions in 1872. At length, the Greek authorities dispatched troops to curtail the plunder, and the Archaeological Society of Athens appointed a professional to excavate what remained.95

Greek officials continued to dig at the site until 1879, and by 1881 Scribner’s could announce that “the California-discovery day is over now in Bœotia . . . The white lines of dry earth, thrown up from avenues of tombs bordering the antique roads and intersecting the green vineyards and yellow harvests of the modern Albanian agriculturists of Greece, have begun to grow green again.”96 The tombs had been thoroughly ransacked and the landscape littered with the fragments of smashed vases. Even so, in 1882, Oscar Wilde, who was proselytizing the English Aesthetic movement in America, wrote lyrically about “those beautiful little Greek figures which in olive woods round Tanagra men can still find, with the faint gilding and the fading crimson not yet fled from hair and lips and raiment.”97 Though out of date, his information came on good authority: J. P. Mahaffy, who had been Wilde’s tutor at Trinity College Dublin, and whom the writer considered his “first and best teacher,” the one who had shown him “how to love Greek things.”98

Published in 1876, Mahaffy’s popular Rambles and Studies in Greece had detailed his first trip, taken only the previous year.99 His name, already renowned, had opened doors to Greek collections, and he found the newly excavated Tanagras in the private homes of Athens “on cupboards, and in cabinets.” Mahaffy was especially struck by their “marvellous modernness”:

The graceful drapery of the ladies especially was very like modern dress, and they had often on their heads flat round hats, quite similar in design to the gypsy hats much worn among us of late years. But above all, the hair was drawn back from the forehead, not at all in what is considered Greek style, but rather à l’Eugénie, as we used to say when we were young. Many hold in their hands large fans, like those which we make of peacocks’ feathers.

For Mahaffy, the figurines attested to the versatility of the Greeks in all matters artistic, “anticipating much of the modern ideals of beauty and elegance.”100 He was not alone in his tendency to turn this era of ancient history into a reflection of the present day. Edmond Duranty regarded the elegant poses of the figurines to be reminiscent of Parisian coquettes, though the turn of their heads, he believed, possessed a quality that was ineffably English. Théodore Reinach characterized the typical Tanagra lady—“always elegant but never affected, always in motion but never in a hurry”—as “truly the Parisienne of antiquity.”101

For prospective collectors, enchanted with these ancient objects that somehow seemed as good as new, the figurines could not be pulled from the ground fast enough. “Every museum, every collection, public or private, made a point of securing some of them,”102 and as early as 1876, fine-quality figurines were selling for at least £40 to £60 apiece—six or seven thousand dollars in today’s currency. Local laborers had been forbidden from selling their finds “to private fanciers,” but examples could be “secretly procured for much smaller sums,” according to Mahaffy, “from persons who have concealed them for private sale.”103 Indeed, the black market for Tanagras flourished even before the general public became aware of their existence. The British periodical press first took note of what was happening in Boeotia in June 1874, when the Academy published a belated account of “the most exquisite terra-cotta statuettes” emerging from the tombs at Tanagra.104 That November it was reported that a small number of “comely Greek ladies” with “uniformly ‘carroty’ locks” had entered the collections of the British Museum and the Staatliche Museum in Berlin, with further additions to the former in 1876, “remarkable for their almost perfect preservation, and for the delicacy and refinement of the modelling.”105

Yet it was not until the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1878 that the figurines were given heightened exposure and a boost in popularity. As Rayet declared in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, the exhibition “has won them public favor.”106 As evidence that they had remained until then virtually unknown, The Illustrated Paris Universal Exhibition describes the terracottas as “curious,” or exciting attention on account of their novelty, and refers to them as “figures, or figurines, in clay”; the italics suggest that the diminutive was still unfamiliar—a specialist’s or foreign term (French, though derived from the Italian figura).107 Rayet was impressed that the burst of popular admiration came not only from those of educated taste, “but also among the Sunday visitors,” the ordinary working class.108

After their spectacular debut in Paris, demand for Tanagras rose to a level where not even the black market could keep pace. The Athenaeum reported at the end of 1890 that some ten thousand specimens had been added to museum collections,109 a number far exceeding the pool of genuine articles, earlier estimated at about seven thousand. While intact Tanagras were growing scarce, new Tanagras were made every day from fragments “picked up and stuck together by the natives.”110 Beyond the figurines cobbled together from bits and pieces were brand new fabrications in the Tanagra fashion, created to appeal to modern taste but wrought to look properly ancient (see cat. nos. 12 and 13). “So perfect are the imitations, even to breaking a statuette into twenty pieces to add plausibility to it,” reported The Times in 1886, “that there are said to be only three people in Athens who are competent to determine their genuineness.”111

As early as 1879, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston accepted a cache of twenty-two Tanagras “lately found in the Bœotian tombs,” the gift of Thomas Gold Appleton and the only collection of its kind then in the United States.112 Scarcely two decades later, “cultured Boston received a severe shock” when it was announced that all but three of them were “rank fakes.”

Heads were found to have been joined to bodies to which they did not belong, and made to fit by filling or scraping, and the bodies are either wholly modern or made up out of ancient fragments, more or less skillfully pieced together, with the missing parts freely “restored” in plaster. In some cases the original parts are so few, or so battered, that one wonders why the fabricator found it worth his while to use them at all.113

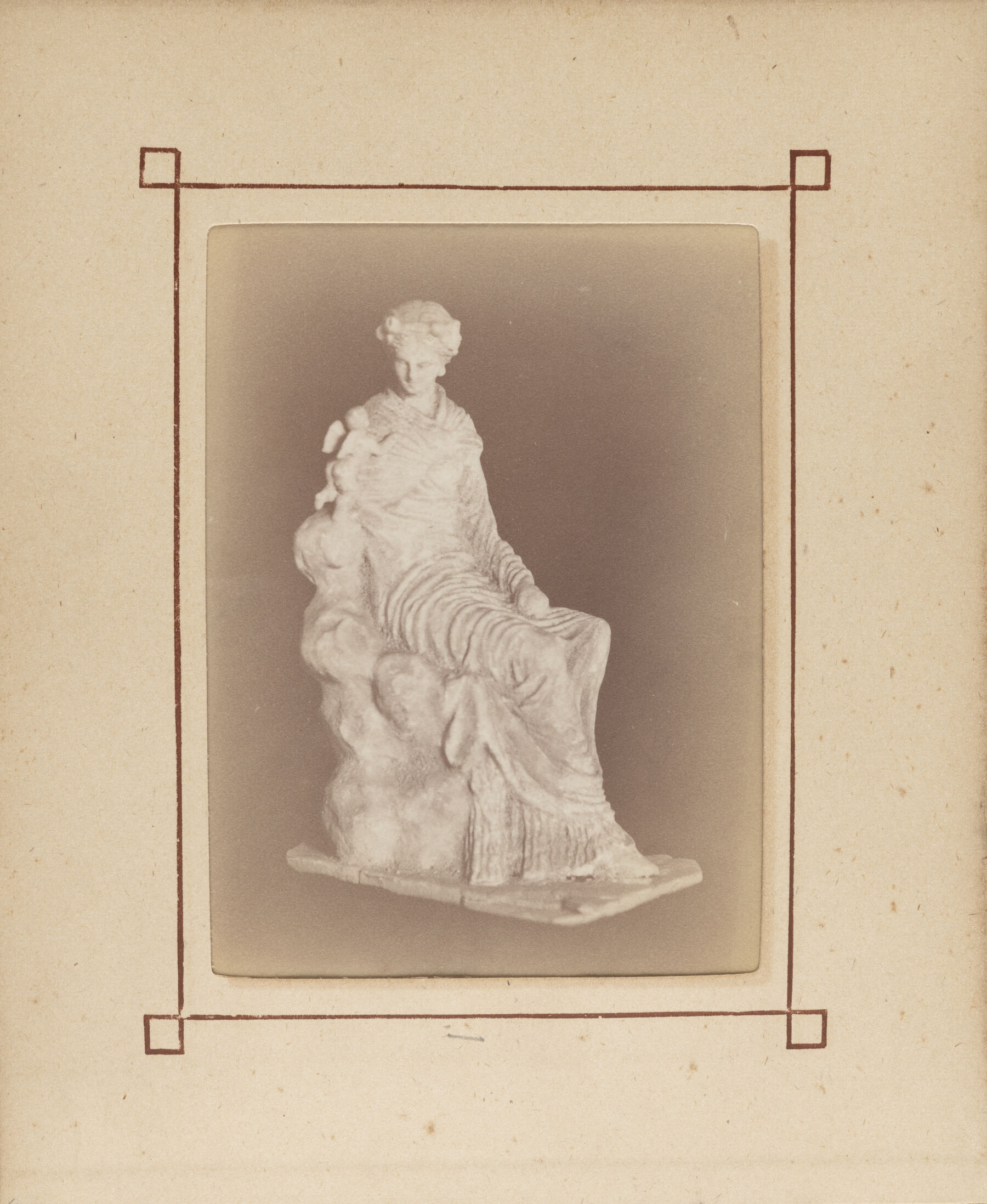

Although some forgeries are so skilled that they can be detected only by an expert eye or technical examination, others are surprisingly easy to spot. After the Exposition Universelle, it appears that the customary standing figures, reticent and tightly wrapped, began to seem old-fashioned, and some connoisseurs sought out figurines with more sensational styles and stories. Their desires were satisfied, as if by magic, with elaborate little groups of figures bearing mythological subjects—the erotic Leda and the Swan (fig. 1.11), for instance, or the sentimental Aphrodite and Eros (fig. 1.12).

Figure 1.11: Photograph of a Tanagra statuette, Leda and the Swan, from the Ionides Album, ca. 1894. Carbonprint on paper in photograph album. Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow; Bequeathed by Rosalind B. Philip (1958), GLAHA:46212. Image © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow.

Figure 1.12: Photograph of a Tanagra statuette, Aphrodite and Eros, from the Ionides Album, ca. 1894. Carbonprint on paper in photograph album. Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow; Bequeathed by Rosalind B. Philip (1958), GLAHA:46290 Image © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow.

These wildly popular putative antiquities were “so extravagant in their poses,” as Reynold Higgins observes, “and so unconvincing in their subject-matter that it is surprising that they deceived anybody.”114 A few Victorian scholars did view the newfound works askance. In 1888, for example, when some questionable figurines went on view at the Burlington Fine Arts Club, the British antiquarian Cecil Torr pointed out that “no terra-cotta of this class has ever been found in any excavation conducted by any government, or society, or responsible person.”115 The catalogue could defend their qualities only on stylistic grounds, noting that the sculptors in Asia (Myrina) “belong to the romantic school,” an explanation that was supposed to account for their more passionate expression. Murray lacked the evidence to rule them out completely but dismissed the newcomers “as foreign in spirit to all that is known of ancient Greek art.”116

Among the most credulous of connoisseurs was Marcus Huish, who had begun to collect Tanagras just before 1890, at the height of the craze: of the thirty or so examples he reproduced in his Greek Terra-Cotta Statuettes of 1900, many drawn from his own and the well-known Ionides collection, at least twenty-two, according to Higgins, “can be seen at a glance to be forgeries.”117 It is therefore no surprise that by the turn of the century museums had begun to relegate their holdings to storage in fear that their figurines might also prove to be fakes; for it was only prudent, wrote Higgins in 1962, “to regard all ‘Tanagras’ as forgeries until they are proved innocent.”118

Object lessons in art

The Athenaeum prophesied in 1878 that of all the antiquities on display at the Exposition Universelle, the Tanagras would hold “the most attraction for artists”—and not just for sculptors, as their surfaces possessed a parallel to works in pastel or watercolor: “The general creamy tone with the faint indications of delicate colour gives an added grace to the exquisite forms.”119 The following year, the Art Journal expressed the hope that the terracottas would demonstrate, for those Victorian painters prone to grandiloquence, “that daintiness in Art can be arrived at with no possible loss of force.”120 In a different era, the terracottas might not have appeared relevant to the development of contemporary art, but understood as decorative objects or drapery studies, they fit the frame of aestheticism, the philosophy of Art for Art’s Sake. Like the modern aestheticist artist, the ancient coroplast “seems to have been guided only by his whim,” as Rayet observed, “to have sought only novelty and grace.”121

By the 1890s, the Tanagra figurine had become so closely identified with refined artistic taste that Oscar Wilde bestowed one upon Basil Hallward, the artist in The Picture of Dorian Gray, as an emblem of his aesthetic position.122 Whistler, on whom Wilde based the artist, did not himself possess a single Tanagra figurine (he could not have afforded one), yet his art naturally aligned with their style of grace and beauty. Whistler was known for the delicacy of his color, the economy of his line, and the daintiness of his touch. Moreover, he consistently opposed the Victorian tendency to measure the worth of a work of art in inches. Among his artistic convictions was that a work’s size and medium were inconsequential: to him, the critic Théodore Duret explained, the Royal Academy extravaganzas which attracted public praise were little more than “merchandise,” while little things made from non-prestige materials—an etching, a paper fan, or “terracottas like those of Tanagra”—could always be “works of great art.”123

It was late in the 1880s, just as popular appreciation for Tanagras was reaching its height, that Whistler began the series of works on paper which imply his own attraction to the figurines. He never admitted to the influence, nor mentioned the Tanagras in a meaningful way in any of his published works or the eight thousand letters that make up his personal correspondence; nevertheless, as Arthur Hoeber wrote of Bessie Potter Vonnoh, another American artist who succumbed to the Tanagras’ charm, “The influence may be traced, even if it be not acknowledged.”124 Whistler’s delicate drawings are made from the same two or three professional models, just as the Tanagra figurines derive from a finite set of molds; they also adopt a similar repertoire of lively but casual poses—standing, seated, leaning, reclining, draping, dancing—as if to modernize the notion of the classical female figure.125

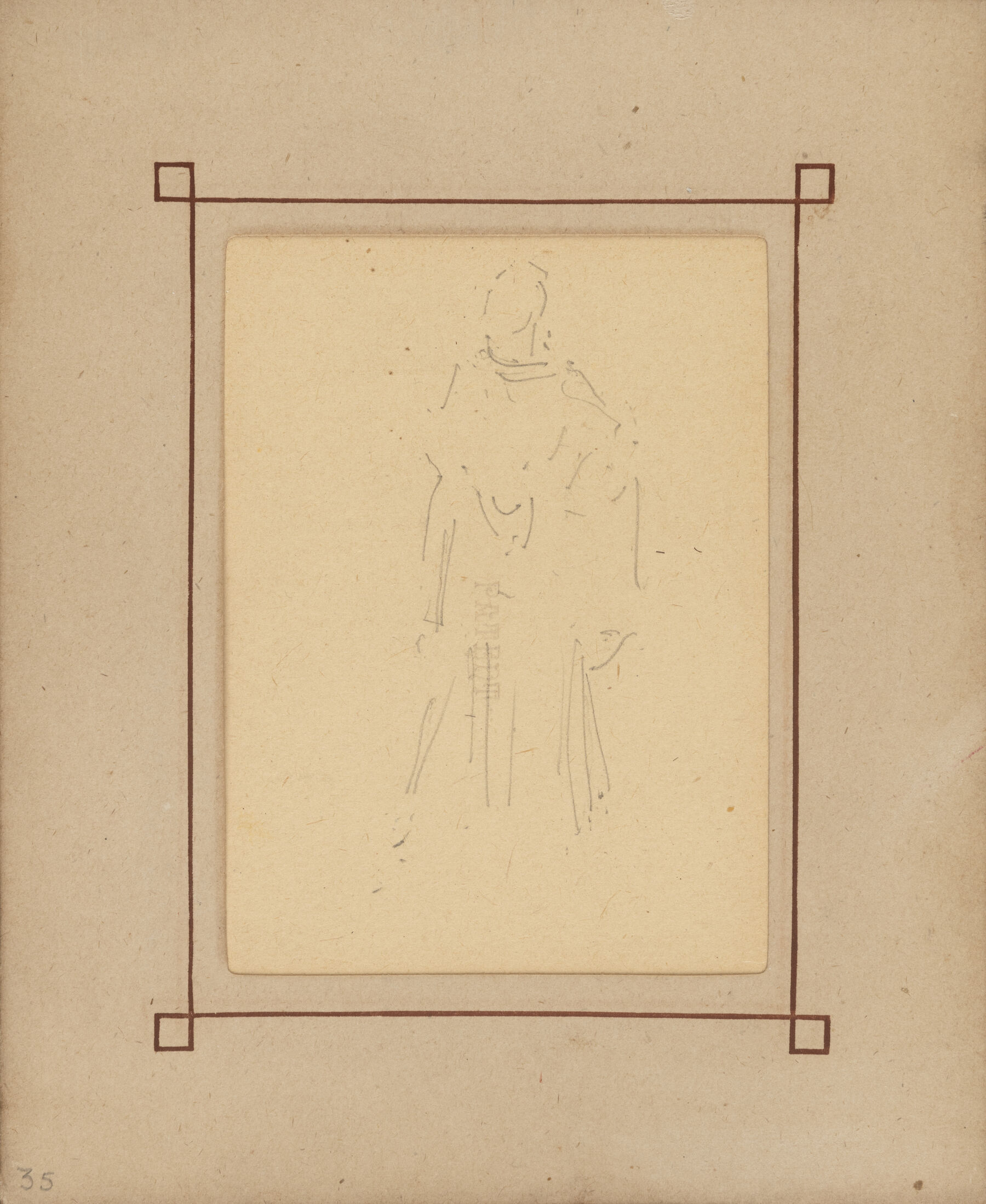

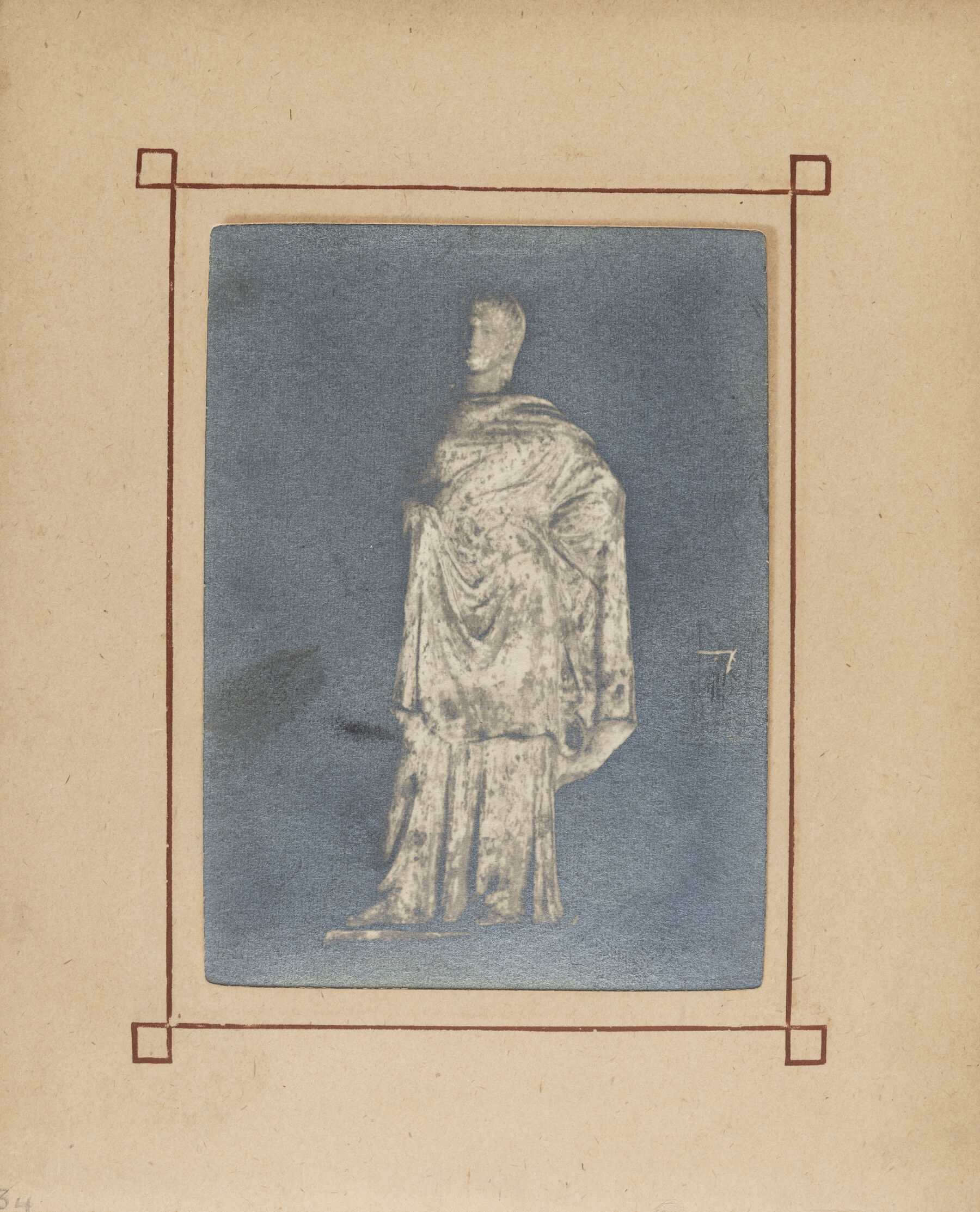

Many of the same connoisseurs who pursued Tanagra figurines had a taste for Whistler’s draped figures. The New York collectors Louisine and Henry O. Havemeyer, for example, bought an impression of the rare color lithograph Draped Figure, Reclining (cat. no. 31) around the same time they purchased a dozen or so purportedly ancient figurines from the renowned Spitzer collection (see fig. 1.13).126 Marcus Huish, the self-proclaimed authority on Tanagra figurines, was also the director of the Fine Art Society in London, and in that capacity organized a groundbreaking retrospective of Whistler’s lithographs in 1895. And the artist’s lifelong friend Alexander A. Ionides, also a patron of Whistler’s art, assembled one of earliest and most important collections of Tanagra figurines in England. We might, then, expect Whistler to have taken inspiration from the actual terracottas he could have seen in person, either in the collections of his friends or the galleries of the Louvre or the British Museum. Yet we should not overlook the probable importance of the illustrations of Tanagra figurines proliferating in contemporary books and periodicals. It is surely significant that Whistler’s only extant drawing of a Tanagra (fig. 1.14)—the mere adumbration of a figurine—was based not on an actual terracotta, but on a photograph of one (fig. 1.15), an image of an object already transposed into two dimensions and translated into black and white.

Figure 1.13: Leda and the Swan, 19th-century version of an ancient figurine. Terracotta, H: 23.5 cm (9 1/3 in.). Shelburne Museum, Vermont, 31.101.1–125.

Figure 1.14: James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903). Sketch after a Greek terracotta figure (M.1419), from the Ionides Album, ca. 1895. Pencil on cream card, 15.5 x 12.7 cm (6 1/8 x 5 in.) Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow; Bequeathed by Rosalind B. Philip (1958), GLAHA:46205. Image © Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow.

Figure 1.15: Photograph of a Tanagra statuette of a standing female figure, from the Ionides Album, ca. 1894. Carbonprint on paper in photograph album. Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow; Bequeathed by Rosalind B. Philip (1958), GLAHA:4639 Image © Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow.

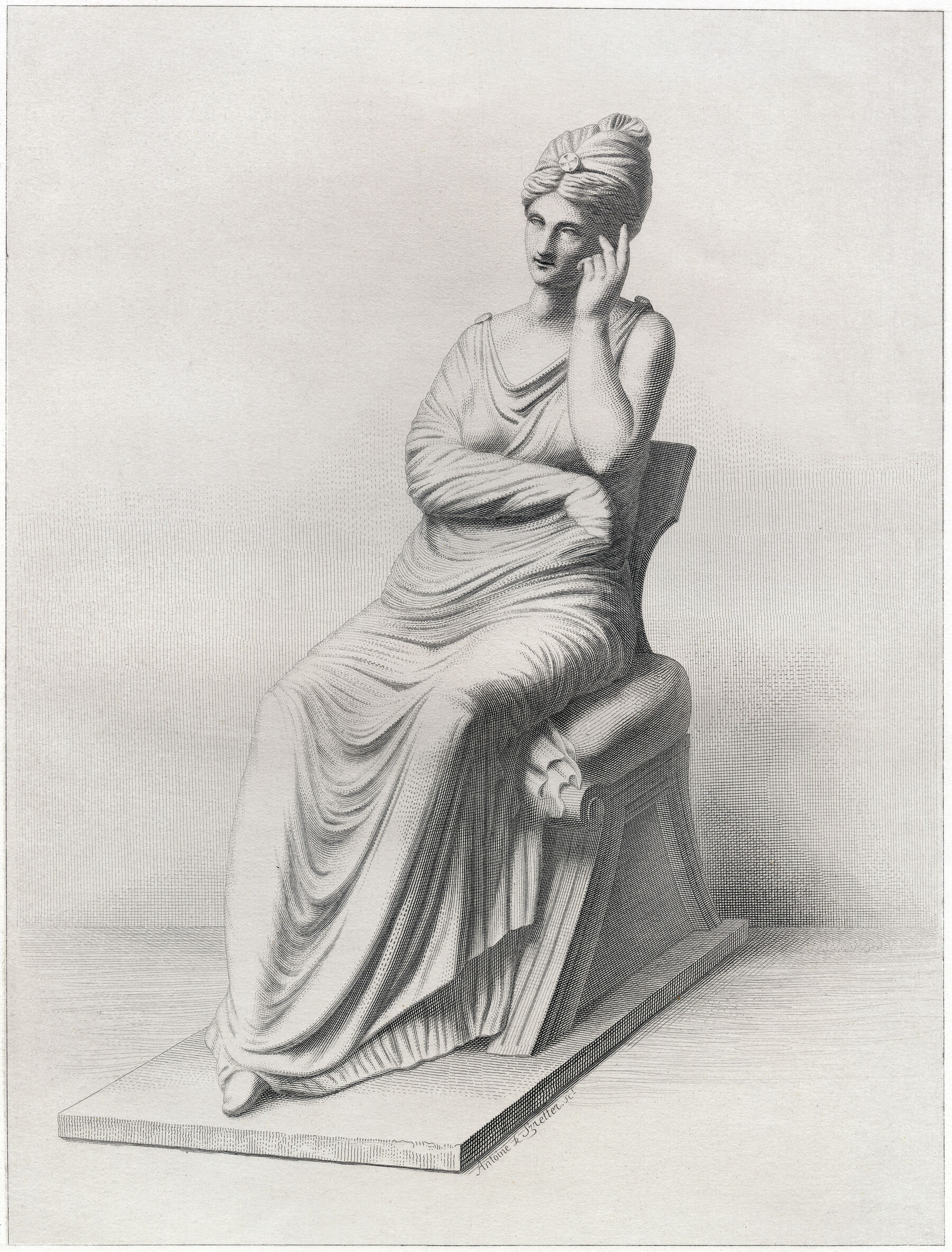

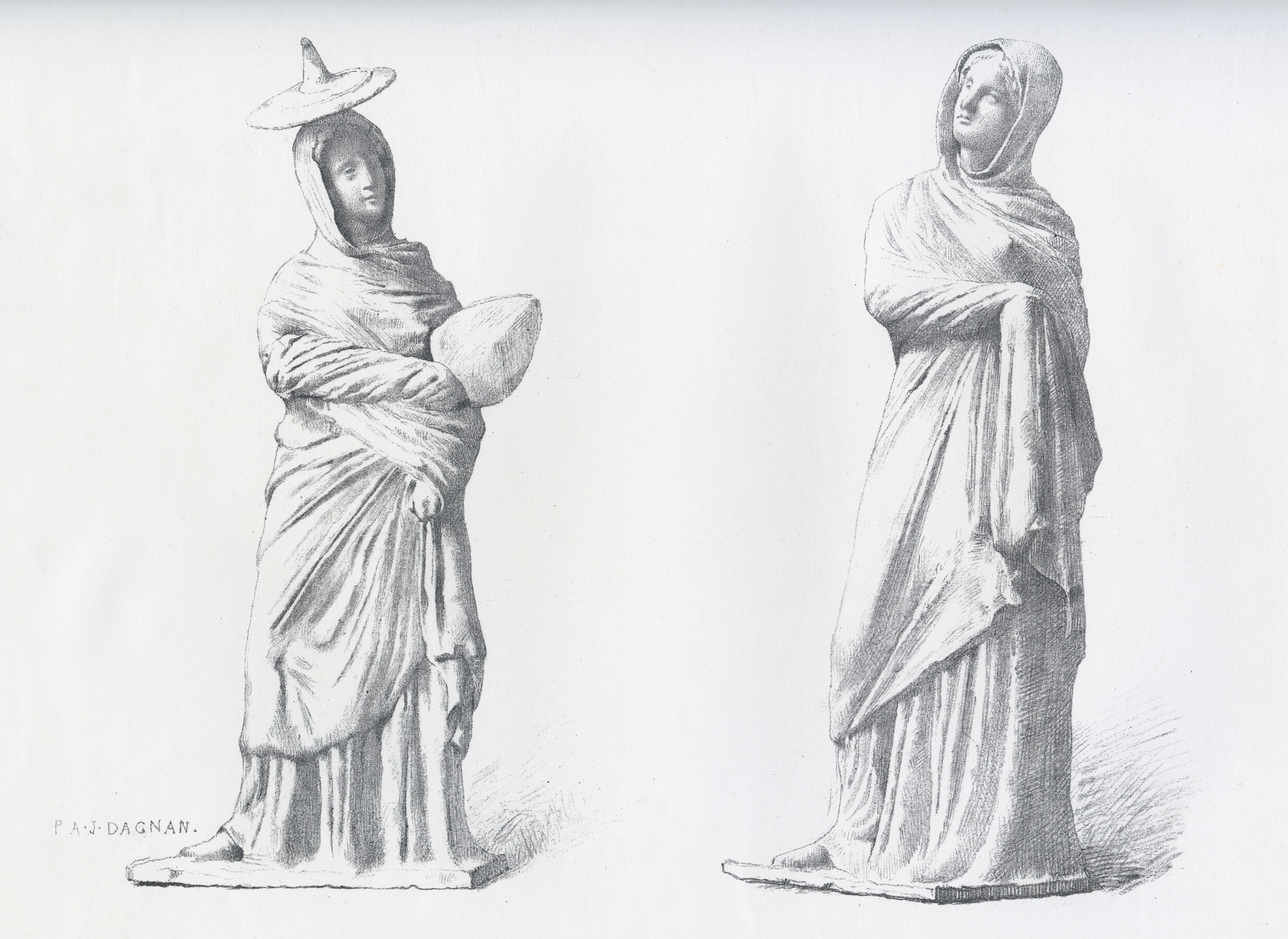

Although that sketch was never intended for public view—it remains hidden away on the cardboard backing of another photograph in a private album—Whistler’s improvisatory drawings on the Tanagra theme were meant to be multiplied, primarily in the form of lithographs. To understand why he chose that medium instead of etching, in which he was already well established, we might compare two illustrations of Tanagra figurines made by different printmaking processes. Both were published in a single volume of the Gazette archéologique: one is a steel engraving (an intaglio, or incised design on a metal plate, like an etching) of a seated Tanagra figurine (fig. 1.16); the second (fig. 1.17), of a pair of standing figures, is a lithograph made by a young student of Gérôme who styled himself P-A-J Dagnan, but later became known as the painter Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret (1852–1929).127 The engraving appears linear and hard-edged, conveying the “austere severity” and stony permanence associated with the High Classical style: nothing about the picture suggests that the figure is small in scale or made from clay. Dagnan’s lithograph, on the other hand, retains the softness of his original sketch, probably made with a greasy lithographic crayon on a smooth limestone slab. Even in black and white, the medium renders a sensitive translation of the tiny, fragile terracotta figurines, lightly dusted with ephemeral pigments.

Figure 1.16: Femme assise, figurine de Tanagra (collection de M. Paravey)* Seated woman, Tanagra figurine (collection of M. Paravey). In Gazette archéologique, edited by J. De Witte and François Lenormant, 2 (1876): plate XXXIII.

Figure 1.17: P-A-J Dagnan (later Dagnan-Bouveret) (French, 1852–1929). Deux femmes drapes, figurines de Tanagra (collection privée de Paris) (Two draped women, Tanagra figurines [private collection, Paris]). In Gazette archéologique, edited by J. De Witte and François Lenormant 2 (1876): plate XX. Image: Public domain.

Beyond its use for illustrations, lithography was put to work in the nineteenth century in the profitable business of reproducing paintings for a popular market. In that respect, the medium finds a parallel in the Tanagra terracottas. “Suppose we regard them as popular editions of works by masters,” wrote Charles de Kay, “suited, by the material in which they are fashioned and the methods used to fashion them, to the slender purses of the people.”128 Whistler may have recognized that the Tanagras, as works of art, transcended their commercial aspect, just as he saw the potential of lithography as a means of original artistic expression. In his hands, one journalist remarked in 1895, “the despised art of the stone long in commercial bondage is again set free for the artist’s service.”129 Moreover, his meticulous attention to details of paper and printing transformed the commonplace “litho” into a precious object.

Nevertheless, Whistler failed to achieve the success he expected when adopting a medium more accessible and inexpensive than oil or etching. In the popular sphere, the “daintiness” of his style worked against him: his subject matter, distilled to its essence, appeared too slight, the drawing too cursory, to justify the cost even of a lithographic print.130 More consequentially, perhaps, Whistler’s Tanagras challenged the norms of Victorian propriety. In a crucial departure from the modestly draped Tanagra figurines, his Tanagra-esque figures are mostly, and sometimes entirely, nude. He did away with opaque drapery as a means of liberating figures he intended to embody the unencumbered spirit of art. What he discovered was that, especially in America, “a nude figure suggests at once the absence of clothes—and general impropriety—only!” His New York dealer informed him that Cameo, No. 1 (cat. no. 39), for example, could not be sold at the price Whistler set “because of the thinness of the drapery.” Indeed, the model’s bare leg is fully exposed as she sits on the side of the bed to bend and kiss a sleeping child—an innocent image if ever there was one, but objectionable to a nation, Whistler observed, “that requires the legs of the piano to be draped.”131

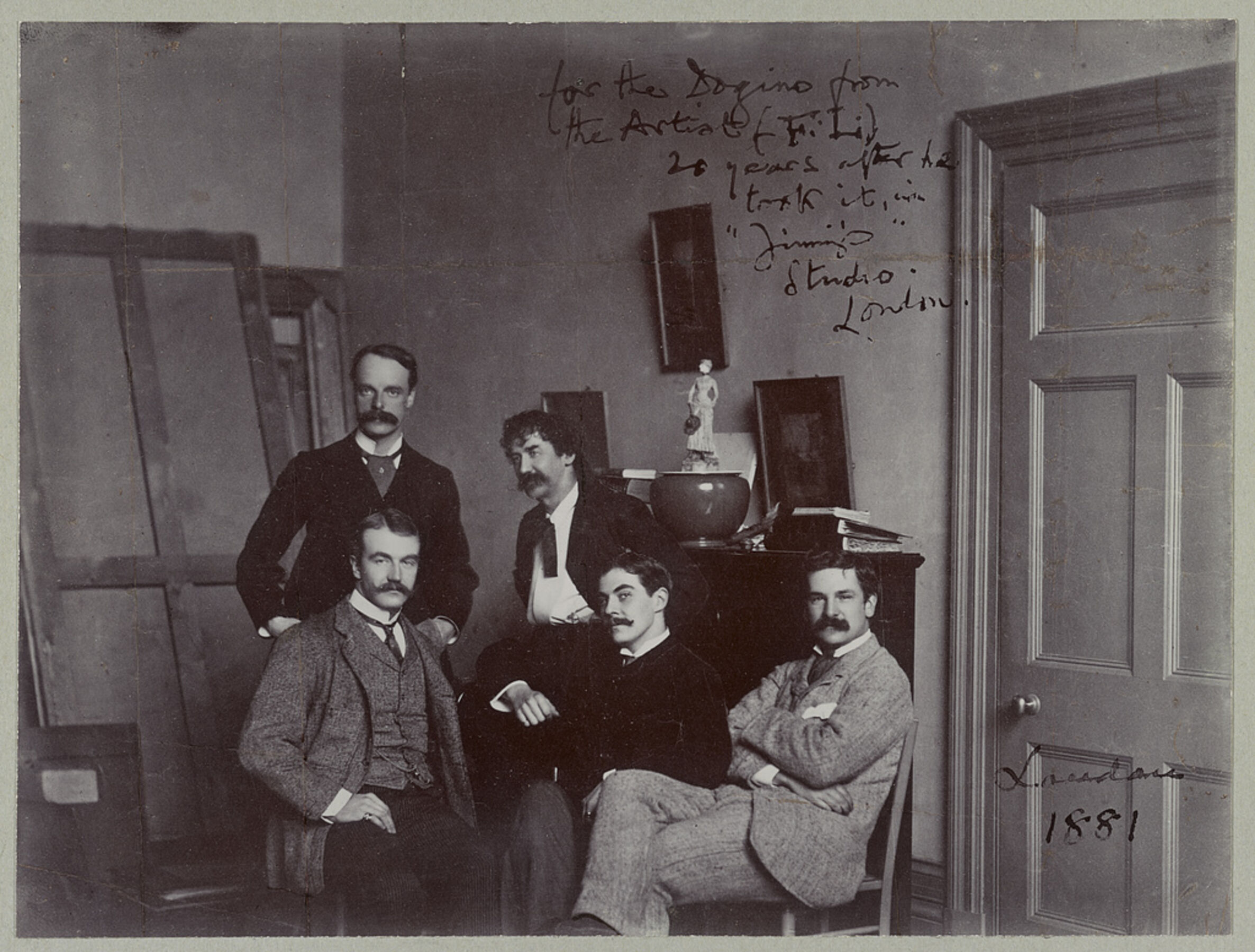

Although Whistler’s Tanagras, primarily executed as lithographs and pastels, imply an interest confined to works on paper, an episode in the early 1880s suggests that the artist may have explored the medium of small-scale sculpture, if only in terms of polychromy. The evidence is a photograph taken in Whistler’s London studio in 1881 (fig. 1.18), which shows a modern statuette of a female figure standing no more than eight inches high, though elevated to become part of the circle of friends: the gathering includes Whistler and Frederick Lawless, the Irish sculptor who set up the photograph; Frank Miles, an English society painter who lived across the street; and the two talented sons of the American neoclassical sculptor William Wetmore Story—Julian, a painter, and Waldo, a sculptor, who happened to be visiting London that year from Rome.132 Made at the time of the terracotta craze and similar in stance and size to a Tanagra statuette, the figurine seems to have been only one in a series of plaster statuettes striking haughty poses and wearing stylish clothing—“charming little swaggerers,” as Whistler referred to them in a letter, “looking prettier than ever.”133

Figure 1.18: Photograph of Julian and Waldo Story, James McNeill Whistler, Frank Miles, and the Honorable F. Lawless in Whistler’s London studio, 1881. Joseph and Elizabeth Robins Pennell Collection of Whistleriana. Library of Congress. Image: Public domain.

When the figurines were eventually packed up and sent home to Waldo Story, Whistler referred to them fondly as “tokens of our work in the studio together,” which suggests a degree of collaboration.134 It is reasonable to assume that Story modeled the figure (shaped it in plaster) and Whistler dressed it with paint; Lawless recollected twenty years later that Whistler had made the figurine himself, though no one else could remember the artist ever trying his hand at sculpture.135 Margaret F. MacDonald also gives Whistler full credit, citing his convincingly comparable, contemporary watercolors of fashionable young women in “swaggering” attitudes, particularly Lady in Gray, of a model who holds a large picture-hat in a similar position to the figure in the photograph.136 The physical evidence that might have settled the question was lost when the “lovely figurines,” though carefully packed, arrived in Rome in pieces.137

In a way that Whistler’s works on paper do not, Story’s little figure looks quaint, almost certainly because of her contemporary dress. In his Tanagra lithographs and pastels, Whistler was able to effectively avoid the trammels of Victorian fashion, which proved particularly exasperating to sculptors of his time. “The freer garb of classic maidenhood presented easier and more inspiring problems to the ancient masters of clay and stone,” wrote Hoeber in 1897, who dearly hoped that “the hideous fashionable dress of the present may by proper treatment be softened and mitigated.”138 Bessie Potter Vonnoh, looking back on the last decades of the nineteenth century, recalled the difficulty of trying to accommodate the “atrocious fashions of the day”—“balloon sleeves, pinched waists, full skirts, funny little hats”— especially on the small scale in which she worked. Although she sometimes depicted modern women in the costume of an earlier, more graceful era, as in the bronze Girl Dancing (cat. no. 46), Vonnoh rarely resorted to classical drapery. Greek sculpture held little appeal for her. What she wanted, she said, was “to catch the joy and swing of modern American life, using the methods of the Greeks but not their subject-matter.”139

Tanagra figurines were gaining popularity in the United States just as Vonnoh was coming into her own as a sculptor. They obviously provided a congenial model for her work, yet she initially denied their influence because, according to Julie Aronson, “they subverted her self-image as a pioneering recorder of modern life in a modern idiom.”140 Eventually, Vonnoh acknowledged her own efforts to capture what one contemporary journalist called “the spirit of the Tanagra statuette, translated into the idiom of the Twentieth Century.”141 Although her statuettes were somewhat larger than the average Tanagra figurine and their facial features more defined, “the fundamental idea and the manner of treatment,” noted the critic Helen Zimmern, “are mutatis mutandis the same”: there were differences between them, in other words, but only because certain aspects had to be altered.142

Vonnoh’s Girl Dancing adapts a traditional Tanagra theme that was also the modern one of a young woman dressed up for a quadrille, and “somehow brings to the gazer’s mind,” the critic Elizabeth Semple remarked, “a vivid sense of what is meant by the phrase 'poetry of motion.”143 The Fan (cat. no. 47) transports another Tanagra model of femininity into the modern age with a pensive young woman in a fashionable tea gown standing with an open feather fan at her side. This figurine is an extremely rare surviving example—one of three—of Vonnoh’s work in terracotta,144 which she took up around 1910, experimenting with different types of clay and degrees of firing and even acquiring a kiln of her own. “Of all the work I have ever done,” she said, the terracottas best reflected her ambition “to have each figure as complete an example of personal work as a picture is of that of the painter.”145

An undated photograph of Bessie Potter Vonnoh shows the sculptor dressed in an artist’s smock, seated in the studio, lost in admiration of one of her own figurines (fig. 1.19). Although the circumstances of the photograph are unknown, Vonnoh appears to have fallen, perhaps ironically, into what had become, by the turn of the century, a visual trope in American art. The archetype may be Gérôme’s female coroplast: Vonnoh, too, is the creator of the work of art she contemplates, of which copies would be made for the marketplace. Other American works on the theme show well-dressed modern women passively appreciating objects of ancient artistry: Tanagra (1901) by Elliott Daingerfield (fig. 1.20), The Tanagra (by 1909) by Thomas Anshutz (fig. 4.13), and The Tanagra Figure (1924) by Alice Pike Barney (1857–1931) all present the principal female figure reflecting upon her miniaturized equivalent in clay.146

Figure 1.19: Bessie Potter Vonnoh with a plaster figurine, n.d. Bessie Potter Vonnoh papers, circa 1860–1991. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Box 1, Folder 18. Image: Public domain

Figure 1.20: Elliott Daingerfield (American, 1859–1932), Tanagra, 1901. Oil on canvas, 28 1/16 x 24 1/8 in. High Museum of Art, Atlanta; Gift of the West Foundation in honor of Gudmund Vigtel, 2010.118. Photo by James Shoomaker. Image courtesy the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA.

A late example of the theme is Tanagra (The Builders) (cat. no. 45) by the American Impressionist Childe Hassam (1859–1935). Its two-part title, considered by the contemporary critic Royal Cortissoz “only nominally relevant,”147 may express the artist’s ambivalence about the premise of the painting, which he defined in 1920 as a “blonde Aryan girl holding a Tanagra figurine.” We can just see “the builders” through the top-floor window of the New York apartment; the secondary theme of urban progress is symbolized, according to Hassam, by the Chinese lilies, “springing up from the bulbs.”148 Yet the figurine is not a Tanagra at all. It may be a replica in miniature of a Greco-Roman Venus, perhaps made of faïence or colored marble of the kind one might purchase in a souvenir shop. More consistent with the Tanagra type is the life-size figure with the Archaic smile, an overgrown example wearing a Knidian hairstyle and a draping negligée. Her chalky complexion and pallid features suggest a fading polychromy; her disproportionately long left arm might be appropriated from a different figurine, or else dislocated from its socket, as it turns from the elbow at an unnatural angle.

The figure stands wedged between a polished mahogany table and a Japanese folding screen, whose vivid colors and patterns are abstracted and dimly reflected in her filmy garment so that she appears pinned to the décor. The tall window offers no escape, as a table has been set in front of it for the purpose of forcing the paperwhite bulbs; sheer curtains have been pulled aside to admit daylight and reveal the view, with only a high, pale rectangle of sky representing the natural world. The oppressive air of Tanagra (The Builders) belies the optimistic message Hassam claims to have intended, “the groth [sic] of a great city.”149 The layers of culture confining the figure may be meant to buffer the shock of the modern—the outside world that had recently entered the First World War. Perhaps the artist regarded the so-called Tanagra figurine as an emblem of Western civilization, which the “Aryan” woman holds out like a talisman against the inevitability of change.

Conversing with the past

For the ancient Greeks who made and consumed the Tanagra figurines, the terracottas represented the feminine ideal, “a well-dressed, mature woman . . . valued in the home, in the sanctuary, and in the afterlife.”150 For the late Victorian scholars who studied and collected them, they reconfigured their concept of antique statuary, casting it in living color and offering access to “a Greece they could feel close to, . . . a Greece that was already bourgeois.”151 But after the turn of the twentieth century, the Tanagras began to lose their glamour. They were dispersed from private collections and removed from museum displays out of a combined fear of forgery and antipathy toward Victorian taste. The term “Tanagra,” however, lived on, and expanded to embrace the new movement of women’s liberation. The Italian feminist Rosa Genoni (1867–1954), an outspoken opponent of the first World War and the Fascist regime, designed the Tanagra Dress in 1908 to wear when addressing the first Italian National Congress of Women. Challenging the contemporary taste for closely tailored styles, the dress balanced “the stitched and the draped,” as the fashion historian Eugenia Paulicelli has noted, and made “a statement of a strong female identity and personality.”152

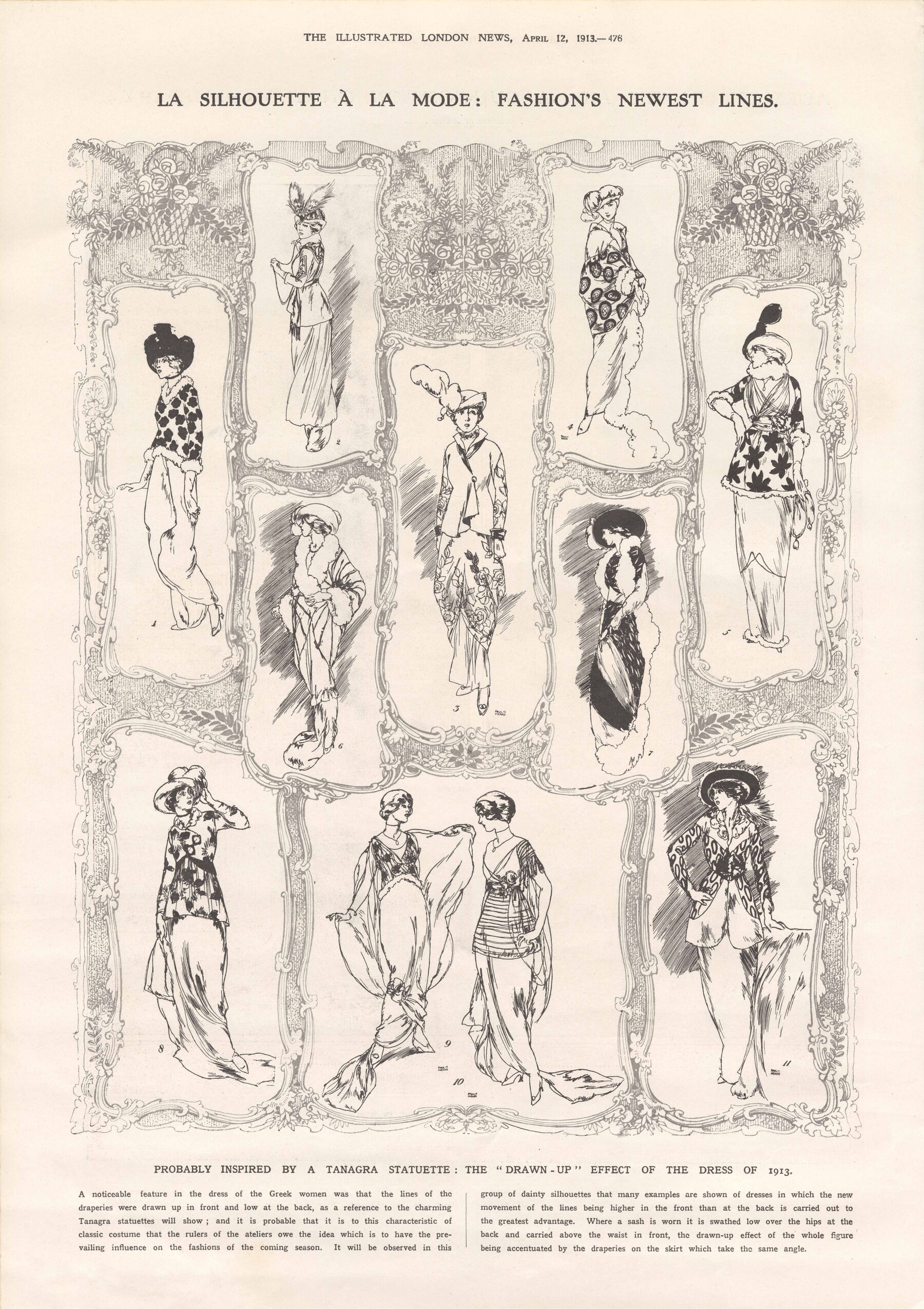

In The Modern Parisienne of 1912, Octave Uzanne writes that “the lady of society” had at last achieved the freedom to choose how she “set off her elegance and beauty” while at home: “She has rediscovered the art of drapery, of arranging materials of harmonious folds, and sometimes delights to wrap herself in clinging gauzy stuffs like the delicious Tanagra statuettes.”153 That new attitude toward tailoring became public in 1913, with a new “silhouette à la mode” predicated on a misunderstanding of Tanagra drapery as “drawn up in front and low at the back” (fig. 1.21).154 Although the new fashion was adopted by Parisian ladies as markers of their modernity, they still felt compelled, as the writer Colette noted in her memoirs, to wear a long “Tanagra corset” underneath, lest their loose garb reflect upon their morals.155 The liberating connotations of the term “Tanagra” were also cast on the art of dance, most famously in Martha Graham’s debut performance as a choreographer in 1926. In Tanagra, Graham (1894–1991) appeared on stage as a figurine in motion, “a Greek figure with a fan, who handled her soft draperies deftly and made beautiful pictures against the black back-drop” (fig. 1.22).156

Figure 1.21: “La Silhouette à la mode: Fashion’s Newest Lines,” Illustrated London News, 12 Apr 1913, 476. Image: Public domain.

Figure 1.22: Martha Graham performing Tanagra. Photographer unknown, ca. 1926. Photograph, 7 x 10 in. Library of Congress, Music Division, Washington, D.C. Image: Public domain.

Like all popular manias, the enthusiasm for Tanagra figurines, and even for the lilting tone of the word itself, eventually faded away. During the postwar period, the terracottas all but disappeared from view, except to the scholars who studied them, and even they were discomfited by the Tanagras’ easy charm: in 1948, one classicist belittled them in his book on Greek ceramics as “young women of light calibre pulling their dresses into pretty patterns.”157 Although Reynold Higgins confidently expected a revival of the taste for them as part of the resurgence of Victoriana in the 1960s,158 the twentieth century, it seems, took little notice of the ancient terracottas.

It was only in 2003 that the figurines returned to the limelight, introduced to the new millennium with Tanagra: Mythe et archéologie, an exhibition organized by the Louvre and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.159 Though dominated by terracottas from the Louvre’s collection, the exhibition gathered figurines from various European museums, which were shown together with a number of nineteenth-century works cast in their image. Another version of that exhibition, Tanagras: Figurines for Life and Eternity, was staged in Valencia, Spain, in 2010.160 Dispensing with the nineteenth-century context, it focused entirely on the Louvre Tanagras, and its outstanding catalogue, published in Spanish and English, offers new art-historical scholarship and technical research, providing a fresh foundation for the further study of Tanagra figurines.

Whistler’s lithographs, after a period of acclaim in the 1890s, had also fallen out of public favor in the twentieth century. For all the artist’s efforts to the contrary, lithography remained closely associated with industrial printing and poster art, and the particular delicacy of Whistler’s lithographs made them difficult to reproduce to good advantage. Moreover, in comparison with his etchings, which had always been held in high esteem, and his paintings, which included one of the icons of American art, Whistler’s lithographs seemed insubstantial and insignificant. In 1998, however, an exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago revived popular and scholarly enthusiasm for this aspect of Whistler’s production.161 Songs on Stone: James McNeill Whistler and the Art of Lithography not only brought the prints out of storage but celebrated the publication of a catalogue raisonné, The Lithographs of James McNeill Whistler, the product of a decade’s research by a gifted team of scholars.162 The comprehensive exhibition and magisterial catalogue together reinstated the significance, and demonstrated the unutterable charm, of this genre of Whistler’s art.

Emanating from Paris and Chicago, those projects are models of art-historical and technical research. They recontextualize the art of Hellenistic terracottas and Whistler lithographs for the twenty-first century, taking their nineteenth-century “discovery” into account. Recasting Antiquity could not have been organized without them, and our work draws from their scholarship to configure a new, and appropriately miniaturized, interpretation of Whistler’s art and Tanagra terracottas. Comprising some fifty objects, the exhibition juxtaposes modern works on paper with the ancient figurines that inspired them, allowing us to better understand how artists conduct conversations with the past, and how the notion of Tanagras as models of ideal femininity was recast from antiquity to suit the desires of the modern day.

-

Frederic Vors, “The Tanagra Figurines,” New-York Tribune, Oct 27, 1879, 5. The epigraph is from Reynold Higgins, “The Discovery of Tanagra Statuettes,” Apollo 71 (1962): 592. ↩︎

-

Marcus B. Huish, “Tanagra Terra-cottas,” Studio 14 (Jul 15, 1898): 99. ↩︎

-

Néguine Mathieux, “Tanagras in Paris: a bourgeois dream,” in Violaine Jeammet, ed., Tanagras: Figurines for Life & Eternity: The Musée du Louvre’s Collection of Greek Figurines (Valencia, Spain: Fundación Bancaja, 2010), 17. ↩︎

-

Henri Houssay, “Deux Figurines de la nécropole de Tanagra,” in J. de Witte and François Lenormant, ed., Gazette archéologique: Recueil de Monuments pour server a la connaissance et a l’histoire de l’art antique 2 (1876), 73. ↩︎

-

Charles de Kay, “A Side Light on Greek Art: Some of the Newly Discovered Terra Cottas,” Century Illustrated Magazine 39, 4 (Feb 1890): 560. ↩︎

-

C.A. Hutton, Greek Terracotta Statuettes (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1899), 44. ↩︎

-

Higgins, “Discovery of Tanagra,” 589; Marcus B. Huish, Greek terra-cotta statuettes: their origin, evolution, and uses (London: John Murray, 1900), 100. See for example J. P. Mahaffy, Greek Pictures: Drawn with Pen and Pencil (London: The Religious Tract Society, 1890), 111: “We must not therefore accept the jibes of the witty Athenians, in whose assumed contempt of the Bœotians, there lay the same suspicion of conscious inferiority that lies in the Irish ridicule of English stolidity.” ↩︎

-

Olivier Rayet, “Les Figurines de Tanagra au Musée du Louvre,” in three parts, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, second series, 11 (1875): 57. ↩︎

-

Hutton, Greek Terracotta Statuettes, 49; R.R.R. Smith, “Goddesses and Women,” in Hellenistic Sculpture: A Handbook (London: Thames & Hudson, 1991), 84. ↩︎

-

“Fine Arts. The Tanagrine Figures,” Athenaeum, 19 Nov 1892, 708. ↩︎

-

Mary F. Curtis, Tanagra Figurines (Boston: Houghton, Osgood and Co., 1879), 36. ↩︎

-

“Tanagra,” Academy, Dec 9, 1899, 667; Jaimee P. Uhlenbrock, “History, Trade, and the Terracottas,” Gifts to the Goddesses: Cyrene’s Sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone 34, nos. 1–2 (1992): 20. ↩︎

-

Huish, Greek terra-cotta statuettes, 4. ↩︎

-

Wilhelm Fröhner, Catalogue of Objects of Greek Ceramic Art exhibited in 1888 (London: Burlington Fine Arts Club, 1888), 64. ↩︎

-

Violaine Jeammet, “The clothes worn by Tanagra figurines: a question of fashion or ritual?” in Jeammet, Tanagras (2010), 135. ↩︎

-

“Greek Terra-Cottas from Tanagra and Elsewhere,” Scribner’s Monthly 21, no. 6 (Apr 1881): 911. ↩︎

-

Hutton, Greek Terracotta Statuettes, 1899, 44; “The Tanagra Statuettes,” The Art Journal 5 (1879): 379. ↩︎

-

Rosemary Barrow, “The Veiled Body: Tanagra Statuette,” in Gender, Identity and the Body in Greek and Roman Sculpture, prepared for publication by M. Silk (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 51; Olivier Rayet, from Monuments de l’art antique, quoted in “Greek Terra-Cottas from Tanagra and Elsewhere,” Scribner’s Monthly 21, no. 6 (Apr 1881): 915. ↩︎

-

Sheila Dillon, “Case Study III: Hellenistic Tanagra Figurines,” in A Companion to Women in the Ancient World, edited by Sharon L. James and Sheila Dillon (John Wiley & Sons, 2012), 233; Malcolm Bell III, “Tanagras and the Idea of Type,” Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin 1, no. 3 (Spring 1993): 41, presenting the research of Dorothy Burr Thompson. ↩︎

-

“Greek Terra-Cottas from Tanagra and Elsewhere,” Scribner’s Monthly 21, no. 6 (Apr 1881): 926. ↩︎

-

See A. Muller, “Artisans, techniques de production et diffusion: le cas de la coroplathie,” in L’artisanat en Grèce ancienne: les productions, les diffusions. Actes du colloque de Lyon, Maison de l’Orient Méditerranéen, 10-11 décembre 1998, edited by F. Blondé and A. Muller (Villeneuve d’Ascq: Université Charles de Gaulle – Lille 3, 2000) (with thanks to Andrew Farinholt Ward). ↩︎

-

“The Tanagra Statuettes,” Art Journal 5 (1879): 380 ↩︎

-

For an example, see “The Painted Lady: Examining Ancient Pigment on Ancient Greek Terracotta figure in the Michael C. Carlos Museum,” by Jada Chambers, Tyler Holman, and Bobby Wendt, Nov 26, 2022. ↩︎

-

Fröhner, Catalogue of Objects, 65. ↩︎

-

Arthur Muller, “The Technique of Tanagra coroplasts. From local craft to ‘global industry,’” in Jeammet, Tanagras (2010), 101. ↩︎

-

Bell, “Tanagras and the Idea of Type,” 50. ↩︎

-

On venting the figurines, see Allen, “Made of Earth, Adorned with Beauty.” ↩︎

-

Uhlenbrock, “History, Trade, and the Terracottas,” 20. ↩︎

-

Huish, Greek terra-cotta statuettes, 1. ↩︎

-