During the nineteenth century, an accidental archaeological discovery of Hellenistic terracotta figurines in Greece engendered a widespread and long-lived cultural mania. The mass-produced little sculptures unearthed, ranging in height from around four to twelve inches (cat. nos. 4, 10), were nicknamed “Tanagras” after the town of Tanagra in rustic Boeotia where local peasants found the first specimens in late 1870. Many figurines preserved their original painted-on colors, and many alluringly depicted women dressed to the nines. Though not dignified by references in Classical literature, these humble miniatures were immediately considered a supreme artistic expression of ancient Greece. Scores of eye-catching figurines were plundered from graves in Tanagra’s ancient cemetery before the Archaeological Service of Athens took over the site. The looted figurines flooded the international art market fanning the flames of Tanagra mania. And, of course, these trendy figurines also captured the imagination of Western artists. The present study examines Tanagra-inspired female depictions in works on paper, paintings, and sculptures from the 1850s to the 1910s by artists active abroad, especially in England and France, and by artists in America.1

Historically, the nineteenth century was primed to embrace these Greek terracottas. Already in the eighteenth century, the German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) had theoretically praised ancient Greek art, initiating a shift from veneration of Classical Graeco-Roman culture toward Hellenism. This orientation was later reinforced by fresh opportunities for a Western audience to see ancient Greek works, like the British Museum’s important display from 1817 of the Elgin Marbles—Classical sculptures taken from the Parthenon and elsewhere on the Athenian Acropolis. Moreover, new excavations in Greece enriched the repertory of extant antique marble sculpture with astonishing Hellenistic originals, including the Venus de Milo in 1820, and the colossal Nike (Winged Victory) of Samothrace in 1863. And both ancient Greek female images were displayed in Paris’s Louvre Museum, thereby enjoying international renown.

Finally, the West was well disposed toward modern Greece, which had won sovereignty from the Ottoman Turks in 1832 after a hard-fought war of independence (1821–1829). And like Japan, which the United States opened for trade in 1853, Greece was regarded as a long-inaccessible, exotic land that had recently become tantalizingly available.

Tanagras Themselves and the Nineteenth Century

The pioneering twentieth-century American archaeologist Dorothy Burr Thompson (1900–2001) argued that—despite their nineteenth-century rustic Boeotian associations and nomenclature—Hellenistic terracotta figurines of Tanagra-type, dating from the later fourth to second century BCE, descended from sophisticated cosmopolitan creations produced in Late Classical Athens earlier in the fourth century. And such Athenian-made figurines were exported in antiquity leading to the production of knockoffs and variants in Boeotia and elsewhere in the Mediterranean world.2 In the nineteenth century, all terracotta figurines were called Tanagras no matter their findspot.

Hellenistic terracotta figurines were mass produced in coroplasts’ workshops, often employing two-part clay molds (cat. no. 2) for front and back, additional molds for features like heads and arms, and some hand-modeled details. A figurine was commonly set upon a slab base, and many had a vent hole on the back to prevent cracking or exploding during firing (cat. no. 4 and rear view). The production process afforded creation of multiples as well as variety in poses and types.3 Survival of multiples is pertinent for considering a modern artist whose specific Tanagran prototypes are not documented.

These clay figurines were embellished with colors after firing—hand-painted over a white clay-slip—including violet, red, rose, pink, orange, yellow, blue, green, and black, as well as gold leaf.4 In modern times, Tanagras preserve evidence not only for the colors of ancient Greek dress but also for the original illusionistic coloring of ancient sculpture.5 The last was debated and still somewhat controversial during the nineteenth century since long-known antique marbles, generally preserved without their original surface paint, were often believed to have been left white, and new marble finds featuring well-preserved color were just beginning to emerge.6 Meanwhile, a Tanagra of a draped woman holding a fan acquired by the Louvre Museum in 1876 and dubbed “Dame en bleu” (“Lady in Blue”) (fig. 2.1) was lauded as a well-preserved exemplar of ancient Greek color and gilding.

Like the Dame en bleu, fashionable Tanagran females (e.g., cat. no. 4) generally wear a himation, a cloak made of wool or sometimes a lighter fabric, over a chiton, a long linen dress. These Greek garments were woven pieces of cloth that were draped or tied rather than cut and tailored like modern Western clothing, and, significantly, ancient artistic representations emphasize the play of their different layers of cloth over the female body and the resulting complex patterns of folds.7 Some female figurines also sport a conical straw sunhat (tholia) or carry a tapered fan (of unknown fabric), and some feature both (e.g., fig. 2.1). The Greek women depicted might be finely accoutered for appearances at public events like religious festivals.8 Hellenistic terracotta figurines and fakes also depicted other characters, including male youths, girls, and the goddess Aphrodite (e.g., cat. nos. 6, 10, 11, 12, 13), but the nineteenth century’s preference for figurines affording glimpses into the daily life and dress of elegant ancient Greek women may have resulted in greater preservation of those examples.9

A unique veiled female figure known as the Titeux Dancer (cat. no. 1) is critical to this nineteenth-century Tanagra story. A rare extant pre-Hellenistic Athenian figurine of circa 375–350 BCE, which is mold made, yet modeled fully in the round,10 this terracotta was named after Philippe Auguste Titeux (1812–1846), a young French architect and archaeologist who discovered it while excavating on the Acropolis in 1846 shortly before his untimely death. Its subsequent amazing history was related by Léon Heuzey (1831–1922), a French archaeologist and Louvre Museum curator.11 Titeux’s effects, including the figurine, were transported to Italy and given to his friend the academic sculptor Pierre-Jules Cavelier (1814–1894), then a Rome Prize winner residing at the French Academy in the Villa Medici.

Cavelier brought the figurine back to his Paris studio and made reproductions of it. Though copies were distributed commercially, the original’s location remained unknown to the public. Finally, Heuzey spotted the real figurine on a visit to Cavelier, who then donated it to the Louvre Museum in honor of his deceased friend. In 1891, the Titeux Dancer finally went on display. Heuzey recognized that this dancing female figurine wrapped in a himation may depict a nymph rather than a human being, but the public took little note. This terracotta, although a Late Classical work from Athens discovered decades before the 1870 Boeotia find, nonetheless was considered the world’s preeminent “Tanagra” figurine. As such, the Titeux Dancer was an incomparably important source of inspiration for Western artists.12

In general, during the nineteenth century, eye-opening, trendy Tanagras were exotic goods, readily available for purchase, at first in Greece, and then directly in Europe, England, and America. The hot art market’s supply was augmented by pastiches assembled with ancient fragments and then also by fakes (see, e.g., cat. nos. 12–13), often brightly colored.13 Small in scale and costing no more than a new Parisian salon sculpture,14 both real figurines and unrecognized fakes were avidly collected internationally by private individuals (e.g., cat. no. 11) and by museums, beginning with Paris’s Louvre Museum (e.g., cat. nos. 3–4). Tanagras first became widely known through a display from private collections at the Paris World’s Fair of 1878.15 They were also published with illustrations: 1878, in Reinhard Kekulé’s Griechische Tonfiguren aus Tanagra;16 1879, in a monograph by Mary F. Curtis, which appeared in Boston;17 and 1883, in León Heuzey’s Louvre Museum catalogue.18 Reinforcing the later Greek focus on female human beings, charming Tanagra figurines struck a chord with some nineteenth-century artists’ burgeoning interest in depicting modern life,19 rather than traditional myth, legend, and history, as championed by the French poet and essayist Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867).20

Artists and Tanagras Abroad

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

The first avant-garde Western artist to pay significant attention to Hellenistic terracotta figurines was the Frenchman Edgar Degas. Since, beyond creating oblique artistic concoctions, Degas unequivocally depicted these figurines, his work provides a firm point of departure. In the 1850s, the young artist copied artworks in Paris’s Louvre Museum, and his preserved sketches reveal unusual choices. Per Theodore Reff, Degas used “Notebook 6,” which is now in the collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, from February to April 1856.21 It contains several sketches depicting ancient Greek sculptural terracottas, including a group of Aphrodite and Eros22 and a very Tanagra-like figurine of a standing draped young woman,23 drawn beside a Greek key pattern.

Degas noted distinctive features of this female figurine in his sketch: her hairstyle terminating in a hand-modeled double chignon projecting upward from the back of her head; the position of her arms, with one bent before her, the other behind her back, and both wrapped in her cascading mantle; plus her left leg, which is bent at the knee so that the toe of her shod foot peeps out from beneath her draperies. Notably, these terracottas that Degas precociously drew in 1856, fourth-century BCE works found at the ancient Greek city of Cyrene (in modern-day Libya), were all acquired by the Louvre Museum in 185024—decades before the famous late-1870 find at Tanagra that brought Hellenistic terracotta figurines to the world’s attention.

Parenthetically, another young avant-garde French artist, the Symbolist Odilon Redon (1840–1916) demonstrated early aesthetic interest in Hellenistic terracottas. A finished drawing he made in the Louvre Museum is after another very Tanagra-like, heavily draped and veiled female terracotta figurine from Cyrene, likewise acquired by the museum in 1850.25 Since Redon registered to copy at the museum in 1862 and 1864, his drawing must date from those pre-Tanagra years.26

This phenomenon of rare Hellenistic figurines known from findspots other than Tanagra eliciting early interest in the genre, including among private collectors, has been dubbed by Violaine Jeammet “des <Tanagras> avant Tanagra.”27 And such interest may be ascribed to Degas on yet another occasion. The young artist left Paris in July 1856 to spend several years in Italy where he copied works by Renaissance artists.28 During this Italian sojourn, Degas also made two studies (see, e.g., fig. 4.1) depicting the Titeux Dancer (cat. no. 1), which, as we have seen, had been discovered in Athens about ten years earlier. In 1850s Italy, rather than the original figurine (which was then ferreted away in Cavelier’s Paris studio),29 he must have copied a cast, perhaps one housed at the Villa Medici in Rome.

Degas’s sensuous pencil-on-paper sketch with a front view of the Titeux Dancer in the British Museum (fig. 4.1) has not heretofore been considered in published scholarship on the artist. “Etude Tanagra,” inscribed in French on its reverse, could only have been written after the 1870 Tanagra find and thus must have been added long after this 1850s drawing was made. Degas’s side view, executed in oil on pasteboard mounted on canvas, always remained in the artist’s possession.30 His two 1850s studies reveal Degas’s interest in this ancient Greek veiled dancer long before the figurine enjoyed a vaunted position in the later context of Tanagra mania. Significantly, the attention Degas paid to the Titeux Dancer in the 1850s—depicting the figurine from two different views—was prophetic of his own later focus on dancers and their movements,31 which from the 1870s on comprised Degas’s main subject matter,32 including for many small wax (or plasticine) sculptures found in the artist’s studio at his death and subsequently cast in bronze.33

Figure 4.1: Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas, (French, 1834–1917), Study after Front View of Titeux Dancer, verso inscribed “Etude Tanagra,” ca. 1857–59. Pencil on paper, 24.1 x 15.6 (9 1/2 x 6 1/8 in.). London, British Museum, 1924,0617.33. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum via CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

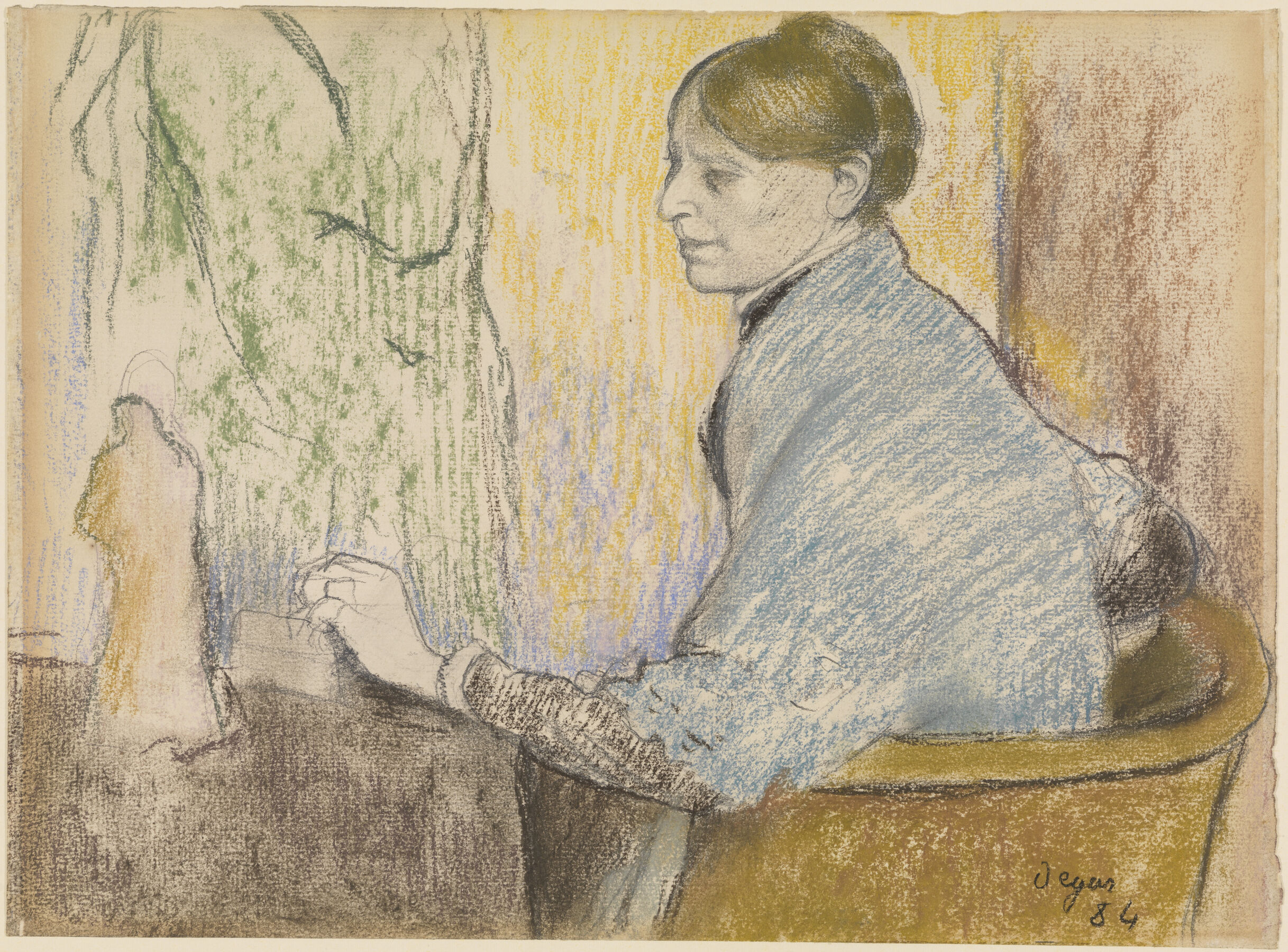

Degas met his close, life-long friend Stanislas-Henri Rouart (1833–1912) when they were teenagers attending the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris in the later 1840s, and, in the 1870s, he served under Rouart during the Franco-Prussian War. Rouart was a wealthy industrialist, a little-known Impressionist painter, and an impressive art collector.34 Degas painted Rouart with his young daughter Hélène (1863–1929) in the 1870s; then, in the 1880s, as Jean Sutherland Boggs has pointed out, he appears to have planned an oil portrait of Hélène with her mother. This painting was never executed, perhaps because the artist feared it might reveal their problematic relationship.35 A pencil sketch, of unknown whereabouts,36 and a pastel in Karlsruhe dated 1884 (fig. 4.2) provide evidence for the planned composition. In the sketch, Hélène is shown at center back, standing with hand on hip, totally wrapped in a heavy mantle whose folds crisscross her body: her pose and attire evoke a draped Tanagra figurine (see, e.g., cat. nos. 4–5). Her mother, Mme Rouart (née Hélène Jacob-Desmalter; 1842–1886), at the sketch’s right edge, is seated leaning on a table. Both women regard the composition’s focal point—a draped Tanagra figurine, shown in profile view, standing on the table.37

Figure 4.2: Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (French, 1834–1917), Mme Henri Rouart in a Chair at a Table with a Tanagra Statuette, 1884. Pastel and pencil on drawing paper, 26.7 x 36.2 cm (10 1/2 x 14 1/4 in.). Karlsruhe, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, 1979-6. Image: Courtesy of Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe.

In the Karlsruhe pastel, Hélène has largely been cropped out save for part of her mantled form appearing in the background. The pastel focuses on the seated Mme Rouart, who once again is shown observing rather sadly a Tanagra figurine standing on the table in the foreground. Since, in the nineteenth century, these terracotta figurines were associated with the findspot in Tanagra’s ancient cemetery, they were often regarded as antique funerary figures. Thus Mme Rouart, who seems unwell here and would die in 1886, may be shown contemplating her own mortality.38 The pastel’s draped figurine, though summarily sketched, is shaded in a pale hue suggesting terracotta. It appears to be shown from the back. Édouard Papet identifies this “petit fantôme voile” (“little veiled ghost”) as the Titeux Dancer (cat. no. 1).39 Save for its head’s leftward tilt, the depicted figurine’s silhouette is indeed comparable to a rear view of the Titeux Dancer, and it likewise does not have a vent hole (see cat. no. 1 and rear view).

Henri Rouart’s brother Alexis (1839–1911) is known to have collected Tanagra figurines; inclusion of a figurine in Degas’s Rouart studies has thus been taken to indicate that Henri might have owned some as well,40 and, therefore, the family’s collecting might have prompted Degas’s association of Hélène’s likeness with these trendy terracottas. Executed in the 1880s—now the height of Tanagra mania—these images stand at the forefront of an important pictorial type representing contemporary women in interior settings contemplating Tanagra figurines (see cat. no. 45). And, if the Titeux Dancer can indeed be identified as his composition’s focal point, for Degas this figurine could well have symbolized this entire genre of terracottas (see figs. 4.1 and 4.2). Regarding Degas’s representation of various artworks in his pictures, Theodore Reff concluded that sometimes a sitter or their family did possess the other work, but most of the time, “the particular work of art seems to have been chosen because of Degas’s own interest in it.”41 And Degas’s depiction of the Titeux Dancer in his maturity would indeed have had a long-term personal significance.

Remarkably, in a later pastel portrait signed and dated 1886, Degas once again depicts Hélène Rouart posed and attired like a Tanagra figurine (see figs. 4.3 and 4.4), with one arm bent behind her back, wearing a mantle wrapped over her dress.42 In Degas’s earlier 1884 pastel (fig. 4.2), the shawl wrapped around Mme Rouart’s shoulders as well as the drapery of Hélène’s cropped form are shades of blue. In the 1886 pastel, Hélène’s mantle and dress are likewise both colored blue. This pastel portrait’s main title Femme en bleu (Woman in Blue), evokes the Louvre Museum’s renowned Tanagra with well-preserved color known as the Dame en bleu (fig. 2.1).

Figure 4.3: Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (French, 1834–1917), Femme en Bleu: Portrait of Mlle Hélène Rouart, 1886. Pastel and charcoal on tan laid paper, 48.9 x 31.8 cm (19 1/4 x 12 1/2 in.). Private Collection. Image: Courtesy of Sotheby’s, Impressionist & Modern Art Part Two, Sotheby’s Sale N01827, Lot 119, November 3, 2005.

In Degas’s 1886 pastel portrait, a bit of white ruffle visible at Hélène’s neck may indicate that the blue dress beneath her mantle is the same one she wears in Degas’s contemporaneous oil portrait in the National Gallery, London, showing her standing in Henri Rouart’s study. And Hélène’s father likewise painted her wearing this blue dress trimmed with white ruffles.43 The National Gallery associates Degas’s inspiration for showing Hélène wearing blue in the oil painting with Henri Rouart having owned the generically titled 1874 oil painting Dame en bleu (“Lady in Blue”) by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875), showing a woman, wearing a blue dress and holding a folded fan, standing in the artist’s studio. But Degas’s 1886 Tanagran Femme en bleu pastel portrait of Hélène suggests that her wearing blue in his oil portrait of her might likewise betray the influence of Tanagras—notably, of the Louvre Museum’s figurine called Dame en bleu (fig. 2.1), exactly like Corot’s painting. Hélène’s sadness in Degas’s oil painting may be associated with the recent death of her mother; at the same time, Hélène’s serious countenance and avoidance of engaging the viewer’s gaze in both Degas’s 1886 pastel and oil portraits of her might reflect the reserved facial expression and contained bearing of some Tanagra figurines (see figs. 2.1 and 4.4). And, while Degas had earlier described Hélène’s red hair and pale complexion as celebrated in Venetian artistic tradition, red hair was also common on Tanagra figurines (e.g., cat. nos. 4, 7, 10).44

Figure 4.4: Draped woman holding a fan, findspot unknown, Hellenistic, ca. 330–200 BC, terracotta with traces of polychrome, H. 18 cm (7 1/8 in.). Paris, Louvre Museum, S 1664. Image: © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

In Degas’s 1886 Femme en bleu pastel portrait, a rounded form emerging beneath the lower edge of Hélène’s enveloping blue mantle must be a fan held in her hidden left hand—fan-holding is widely attested on Tanagra figurines (see, e.g., fig. 2.1). And Hélène’s pose here appears to have been patterned after a fan-holding figurine of ca. 330–200 BCE (fig. 4.4) in the Louvre Museum, possibly from Tanagra, whose venerable acquisition date is unknown.45 Boggs—probably not conversant with the ancient prototype—misunderstood Helene’s fan in the pastel as a bag.46 But instead of the tapered ancient Greek fan characteristic of Tanagra terracotta figurines, Degas has here substituted a broader rounded model, recalling popular imported Japanese non-folding uchiwa fans. Notably, particularly between 1878—the year of a World’s Fair in which Japan participated—and 1880, and again around 1885, Degas himself decorated salable Japanese-influenced art fans.47 A couple of Degas’s fans were even owned by Henri Rouart and his brother Alexis.48 Moreover, the fact that the Tanagras’ elegantly accoutered ancient Greek women sported hand fans would have delighted a nineteenth-century audience besotted with both imported Japanese fans and French creations. Documenting the vogue, fashionable Parisian women were frequently depicted holding fans in contemporary art, as in Mary Cassatt’s The Loge or Degas’s Ballet from an Opera Box.

James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

Whistler and Degas have commonly been linked on account of their rabid interest in then popular Japanese products, like fans and prints, which both men also collected.49 Turning to ancient terracotta figurines from modern Greece for artistic inspiration constitutes another bond. Neither artist visited Japan or Greece,50 however; their cultural knowledge was based upon commercially available imported goods, objects displayed in private collections, expositions, and museums, plus illustrations and photographs.

An American expatriate, Whistler studied art in 1850s Paris, where he first met Degas, but after 1859, he resided in London and traveled between the two cities until relocating to Paris in 1892. Significantly, in London, Whistler was close to the hospitable family of British-Greek shipping merchant and artistic patron Alexander Constantine Ionides (1810–1890), whose youngest son, Whistler’s long-term acquaintance Aleco (Alexander Ionides), collected Hellenistic terracotta figurines like his father.51 With their Greek connections, the Ionides family reputedly purchased stray Hellenistic terracottas found in Boeotia before Tanagra’s discovery, perhaps as early as the 1850s and 60s.52 However, such very early acquisitions cannot be documented. And, since a photo album of Aleco’s collection given to Whistler years later contains numerous fakes, which were not produced until after Tanagra, and employs photographic paper not patented until 1879, it must largely reflect later Ionides collecting.53

Whistler has, nonetheless, been indiscriminately credited with displaying artistic influence from Hellenistic terracotta figurines well before the major late-1870 find at Tanagra. Whistler’s The Six Projects, oil sketches for an unrealized commission, looms large among erroneously cited works.54 In several sketches, women wear vaguely classicizing garments summarily described with flowing strokes of paint; a few carry a Japanese parasol or fan. Instead of reflecting Tanagra figurines, these generalized images “show groups of female figures in various configurations, reminiscent of the Parthenon frieze but without the consistent orientation of a procession.”55 And, in mid-1860s London, artists like Whistler and his new friend, the painter Albert Joseph Moore (1841–1893), were looking at the Parthenon sculptures, freshly reinstalled by the British Museum, rather than the museum’s few Hellenistic terracotta figurines from findspots other than Tanagra.56

Whistler artworks possibly begun as early as 1869 or 1870 do display an impact of figurines perhaps discovered just before Tanagra,57 which might have been in the Ionides collection. To begin with the clearest, if not necessarily the earliest, example of influence, Whistler’s drypoint The Model Resting (Draped Model) (fig. 4.5), showing a young woman in a contrapposto pose wrapped in a mantle worn over a long dress, has appropriately been compared to Tanagras.58 It mimics an eminently Tanagran way of depicting a Greek himation worn over a chiton and explores the characteristic resulting play of draperies across a female body. At the left, the mantle’s lower end, draped over the model’s hidden right arm, projects away from her body as it hangs downward, thus reflecting a distinctive Tanagran motif. The model’s left arm can be discerned beneath the cloth bending up sharply at the elbow so that the hand nearly touches her chin. This arm-toward-chin motif, rather than referencing women in Japanese prints, reflects a gesture characteristic of Hellenistic terracotta figurines (see also cat. nos. 5 and 8).59 The ancient raised-arm motif may be employed for the right arm or reversed for the left.60 Aspects of Whistler’s draped model’s pose occur most compellingly on Tanagra figurines purchased by the British Museum in 1874–75, though these acquisition may postdate the print, and the specific prototype Whistler knew remains undocumented.

Figure 4.5: James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903), The Model Resting (Draped Model), butterfly monogram, 1870. Drypoint, printed in black ink on ivory laid paper, sheet: 33.3 x 19.9 cm (13 1/8 x 7 7/8 in.). New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1917, 17.3.67. Image: Public domain courtesy of the Met’s Open Access Policy.

His design for a fan at the Colby College Museum of Art depicting women at the shore wearing long, flowing garments, with one carrying a parasol (fig. 4.6), emerges from Whistler’s 1868 work on The Six Projects, such as Symphony in Blue and Pink. While a decorated fan featuring a parasol may evoke Japonisme, ancient Greek associations dominate this depiction of draped women.61 Significantly, the fan’s most clearly described female figure, dressed in blue and located left of the composition’s center, is unmistakably indebted to Hellenistic terracotta figurines. The Tanagran arm-toward-chin motif (see cat. nos. 5 and 8) observed on The Model Resting (Draped Model) (fig. 4.5), notably also occurs on this fan’s blue-draped female figure. Moreover, her enveloping blue mantle has been pulled up over the back of her head evoking the veiling of ancient Greek women common on these terracotta figurines62 (see fig. 2.1; cat. nos. 3 and 8). Once again, Whistler’s specific prototype is not known.

Figure 4.6: James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903), Design for a Fan, c. 1870. Watercolor, gouache, and pencil on paper, sheet: 17.5 x 49.5 cm (6 7/8 x 19 1/2 in.). Waterville, Maine, Colby College Museum of Art, The Lunder Collection, 2018.107. Image: Courtesy of Colby College Museum of Art.

Hellenistic terracotta figurines suddenly attracted Whistler’s attention beginning around 1869–1870, and the artist mined them for eye-catching motifs of pose and drapery. This exciting new font of ancient Greek female imagery—namely, small three-dimensional artworks—afforded a clinically archaeological depiction of layers of ancient garments draped over the female body. In contradistinction to extant battered and/or more formal-looking—if sometimes similarly posed—ancient marble statuary,63 these charming, accessible terracotta female miniatures could be well preserved down to the extremities, enhancing their appeal as prototypes for Whistler’s confections.64

By contrast, the artist’s mid-1860s paintings featured Western women wearing Japanese kimonos that often hang loosely like a dressing gown rather than being wrapped around the body and bound by an obi (sash).65 Japanese prints with their flattened pictorial space did not present clearly how these patterned exotic garments were designed to be worn. Thus Whistler’s kimono-clad women inhabit a realm distinct from these Tanagra-informed, classically draped females.

An intriguing oil sketch by Whistler showing a female figure holding a fan at the Maier Museum of Art in Lynchburg, Virginia (cat. no. 14), may be reassessed here. Its draped model looks out at the viewer while posed before a Japanese vase, flowers, and hanging Japanese uchiwa fans. This painting has an intriguing backstory in modern scholarship. In 1960, Andrew McLaren Young linked the Lynchburg oil sketch with a Whistler drawing in Glasgow depicting a similarly dressed and posed female figure likewise holding a fan. He believed that Whistler had inscribed the drawing with the name Tanagra, which he applied to both images. Young considered both works to be inspired by a Tanagra figurine of a veiled woman holding a fan in the Ionides collection photo album;66 his conclusions were generally accepted.67 Subsequently, however, the Glasgow drawing’s Tanagra inscription was reassessed as not dating from Whistler’s lifetime. And the title Tanagra has been dissociated from Whistler’s Lynchburg oil sketch.

Whistler’s abovementioned 1860s paintings featuring Western women wearing kimonos in settings filled with East Asian imports exemplify his construct of Japonisme.68 But, despite its Japanese props, ought Whistler’s oil sketch be shifted away from Tanagran inspiration? Does the Lynchburg female figure evoke a kimono-clad woman inspired by a Japanese woodblock print or a woman clad in garments resembling an ancient Greek chiton and himation inspired by a Tanagra terracotta figurine?

First, a Greek contrapposto lies behind the swaying pose of the oil sketch’s woman. A compositionally related crayon drawing by Whistler dated 1869 (fig. 3.1) depicts a classically statuesque nude female figure holding a Japanese fan and standing before a Japanese vase.69 This drawing reveals the influence of his friend Moore’s oil painting A Venus, likewise of 1869, which juxtaposes a nude female figure, classical in form,70 Asian pottery, and abundant flowers. Moore’s purposely ahistorical mingling of elements from different times and cultures in the name of aestheticism, or art for art’s sake, was likewise embraced by Whistler.

Second, despite the Japanese props in the Lynchburg oil sketch, its female figure’s dress is demonstrably based on the Greek chiton and himation. In fact, Whistler’s figure bears an astonishing resemblance to a similarly clad female figurine found at Tanagra (fig. 4.7), which counted among the initial specimens to enter the Louvre Museum. This unique example was purchased in 1872 through Olivier Rayet (1847–1887), an archaeologist and historian of ancient art (see cat. no. 52), who acquired in Athens the finest newly emerging terracotta figurines from Tanagra during the early 1870s.71 Though this Tanagra does not hold a fan (and the right arm is broken), its potent similarities with Whistler include its bare—not veiled—head looking out toward the viewer; its contrapposto pose, emphasized by the himation shown pulled around the figurine’s bent right knee and calf, and lower body; its himation worn over only one shoulder thus exposing the chiton’s upper portion; and, finally, its himation’s end tossed over and concealing the left arm and hand. (Interestingly, in the sketch, through contrasting color plus pattern, the himation’s bunched upper edge may be interpreted as a scarf or sash.) Whistler’s pale colors and their application have been held to reflect pigment remains on the surface of Greek terracotta figurines—an observation that might well apply to the loosely streaked drapery here.72 If the oil sketch does indeed betray knowledge of this particular Tanagra, newly displayed in the Louvre Museum, work on it would have extended to 1873, when Whistler visited Paris.73

Figure 4.7: Draped Woman, Boeotian, Tanagra, Hellenistic, ca. 330–200 BCE. Terracotta with traces of polychrome, H. 22.9 cm (9 in.). Paris, Louvre Museum, MNB 447. Image © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

The source for Whistler’s Lynchburg oil sketch has usually been identified as a female figurine holding a tapered fan from the Ionides collection photo album.74 Though the Ionides figurine’s himation’s end tossed over an arm is similar, its heavy draping and veiling, downcast head, and introspective nature seem at odds with Whistler’s lithe outward-staring female. Young pointed out that the fan type Whistler depicted is the rounded Japanese uchiwa hand fan rather than the Tanagra figurines’ tapered fan.75 As we have seen, Degas makes a comparable Japanese-for-Greek fan substitution in his 1886 Tanagra-inspired pastel portrait of Hélène Rouart (see figs. 4.3 and 4.4). Whistler commonly depicted models—including the nude in his 1869 drawing (fig. 3.1)—holding uchiwa hand fans from his collection. And a photograph of Whistler’s studio at his London residence in Chelsea from 1866–1878 documents these fans hanging decoratively on a wall.76 The Lynchburg oil sketch is, finally, a product of this Whistler studio.

Should the title Tanagra be revived? Whistler’s bold formulation of this painting’s female subject (cat. no. 14) is, indeed, ultimately Grecian, springing from a classicizing female nude (fig. 3.1) whose dressed configuration reflects features of a Tanagra figurine (fig. 4.7). That said, this artwork undoubtedly exhibits the aesthetic synthesis juxtaposing elements from ancient Greek and Japanese culture dubbed “Greco-Japonisme.”77 Taking a cue from Moore’s A Venus, Whistler’s oil sketch might be called A Tanagra.

Later in his career, Whistler displayed an interest in Tanagra figurines once again. In The Rose Drapery, a watercolor and chalk image from around 1888–1895, Whistler appears to simulate colors associated with originally brightly painted Tanagras.78 A Study in Red (fig. 3.9), a crayon and pastel drawing, circa 1890, related to Whistler’s late lithographs like Draped Model, Dancing (cat. no. 25), was exhibited in Paris in 1903 as Danseuse athenienne.79 This display designation perhaps suggests that the pastel’s lithe dancing model, with left arm akimbo and right arm covered by her garment, whose clinging draperies sensuously reveal her body, evokes the Athenian Titeux Dancer (cat. no. 1).80

The Ionides family proudly showed figurines in the groundbreaking public exhibition of Tanagras at the Paris World’s Fair of 1878. However, in 1894, Aleco Ionides asked Whistler for help selling his collection, and, by this date, he had given the artist the abovementioned photo album. Interestingly, Whistler made a pencil sketch after the photograph of one Tanagra figurine reproduced in the album and mounted it on the opposite page (figs. 3.3 and 3.4).81 His owning the Ionides photo album later in life when Tanagra figurines inspired the artist’s work anew is surely significant.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904)

The allure of ancient Greek terracotta figurines was not limited to avant-garde artists. The French academician Jean-Léon Gérôme was a renowned painter, particularly of Orientalist and historicizing classical themes, who also became a sculptor. He enjoyed his greatest public triumph at age sixty-six in the Salon of 1890 with a personification in marble sculpture of the archaeological site at Tanagra that yielded the terracottas (fig. 4.8).82 His life-sized statue depicts a naked female figure perched on a high, haphazardly excavated earthen mound revealing exposed figurines, including the Titeux Dancer (cat. no. 1);83 a pickaxe leans against one side. At the front, ΤΑΝΑΓΡΑ (“Tanagra”), chiseled in Greek capitals, is inscribed on a tablet with handles on its side ends (tabula ansata). Rather than a Tanagra figurine, in its extended left hand, this statue holds a hoop dancer statuette created by Gérôme, which was probably loosely inspired by the Titeux Dancer in conjunction with a then-esteemed figurine (since recognized as fake) depicting a naked female with a hoop.84 And statuettes of Gérôme’s own hoop dancer (cat. no. 44) were available separately.85

Figure 4.8: Jean-Léon Gérôme (French, 1824–1904), Tanagra, 1890. Marble, photogravure Goupil c. 1892. Image: Public domain.

The Vatican Museum’s Roman marble copy of the lost Hellenistic bronze Tyche (Fortune) of Antioch by the sculptor Eutychides—a female personification of the city seated on a rock—is held to be a monumental ancient source for Gérôme’s Tanagra.86 Yet Tanagra figurines and forgeries are themselves sometimes seated, often on rocks (see also, e.g., cat. nos. 7 and 11). And Tanagra’s conceit of holding a female statuette in her hand recalls that the lost colossal Athena Parthenos by Pheidias, the Classical gold-and-ivory cult image of the Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis, held a Nike (Winged Victory) in its extended right hand.87 Not only did attempts to reconstruct the Parthenos loom large in the nineteenth century,88 but a well-preserved small copy, the Pentelic-marble statuette known as the Varvakeion Athena, was found in Athens in 1879.89

Gérôme was fascinated with photography, and photographs taken in his studio illuminate both his professional association with and voyeuristic depiction of naked female models. The artist’s 1886 oil painting The End of the Sitting, portraying Gérôme’s still-disrobed model draping with cloths the clay prototype for his nude statue of the Lydian Queen Omphale,90 may be juxtaposed with a series of black-and-white photographs by Louis Bonnard showing, in various views, Gérôme, the nude model, and the clay sculpture in the artist’s studio.91 A separate photograph shows a studio model posing naked for Gérôme’s statue of Tanagra.92 Personifying a Greek archaeological site renowned for its dressed female images with a naked statue was consonant with Gérôme’s voyeuristic artistic preference for disrobed female subjects and his overwhelming reliance upon studio models, as well as with the longstanding Western association of female nudity and the classical world. This combination of potent stimuli resulted in an uncanny modern monument.

Gérôme, moreover, controversially painted his Tanagra statue’s surface with tinted flesh, pink lips, blue eyes, brown nipples, and brown hair. He was heeding the mounting evidence for ancient sculpture’s surface color supplied not only by well-preserved Tanagra terracotta figurines, but also by recent marble finds like the fourth-century BCE Alexander Sarcophagus discovered in 1887 at Sidon, Lebanon, by a Turkish student of Gérôme, Osman Hamdi Bey (1842–1910).93 And when Gérôme commissioned quarry workers to find marble for Tanagra, he requested a block that would take color well.94 The statue’s color was removed during over-zealous cleaning in the 1950s, save for the polychromy on the hoop dancer.95 Coloring Tanagra figured in Gérôme’s quest to achieve modernity by astonishingly tweaking academic realism, and he painted all his subsequent sculptures down to his final work of 1903, the plaster personifying the Greek city of Corinth as a sacred prostitute.96

In the painting Working in Marble, or The Artist Sculpting Tanagra of 1890,97 Gérôme depicts himself—alongside the posing flesh-and-blood female model—toiling on his white plaster original for the marble statue, which would be carved by stone workers. The painting’s visual play—alluding to his intended lifelike coloration of the Tanagra marble statue all’antica—recalls Pygmalion. And, around this time, Gérôme actually painted the classical theme from the ancient Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses of the sculptor Pygmalion, who fell in love with his own statue of Galatea, which was then brought to life by the goddess Venus.98 In the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s version, which appears in the background of Working in Marble, as Pygmalion and Galatea passionately embrace, color documents her metamorphosis in progress from white marble to living flesh.99

In two paintings from 1893, Sculpturae vitam insufflat pictura (“Painting Breathes Life into Sculpture”) (fig. 1.5) and Atelier Tanagra (fig. 1.6), Gérôme imagines the ancient production and sale of Tanagra figurines.100 As Susan Waller observes, Gérôme’s

completely feminine cast of characters . . . serves to gender production and consumption of these works. While it is, in fact, unlikely that the original artists were female . . . the gender of the craftswomen in Gérôme’s painting resonates with the French debates in the 1890s about the capacities of women artists. Though they were excluded from the École des Beaux-Arts, women had long been admitted to the École Nationale des Arts Décoratifs, since the decorative arts were widely considered an appropriate field for what were believed to be their distinctly lesser capabilities.101

Interestingly, the Greek female artisan in each painting is shown coloring Gérôme’s own then-commercially-available hoop dancer (cat. no. 44) rather than an actual Tanagra figurine. Meanwhile, his Tanagra workshops’ Greek female clientele are themselves accoutered to resemble these ancient terracotta figurines down to their sunhats perched at rakish angles. In the nineteenth century, shopping was a rare respectable public freedom allowed women. Already in the 1870s, Edgar Degas had begun depicting milliners in images such as At the Milliner’s and The Military Shop, showing fashionable women shopping for hats waited on by saleswomen, and also women making hats, then an indispensable fashion accessory sold at the thousand millinery boutiques in nineteenth-century Paris.102 Both artists thus reaffirm that contemporary shopping (especially for artisanal products) was an appropriate subject for modern art. As Sheila Dillon points out, “the renowned French archaeologist Theodore Reinach called the Tanagras ‘the Parisiennes of antiquity,’ thereby equating the figurines with the chic women of modern Paris.”103

Gustav Klimt (1862–1918)

Outside of France, in 1890, the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt was busy working on an early important commission—decorating the grand staircase of Vienna’s recently built Kunsthistorisches Museum. The program, devised by the museum’s head curator, called for depictions of different artistic periods featured in the museum’s collection that incorporated representations of actual works of art. The architectural decoration consisted of oil paintings on canvas affixed to the museum’s walls. Klimt carried out thirteen of the forty-two paintings commissioned from his Künstler-Compagnie, including the two for Ancient Greece,104 which he embodied by means of two distinctly different female figures. One is the armed warrior goddess Pallas Athena depicted in a spandrel here as an imposing, frontal, immortal female figure silhouetted against a halo-like golden round shield, who supports a bronze statuette of a winged victory in the palm of her right hand. Klimt’s hieratic goddess is another nineteenth-century artwork that evokes the lost Athena Parthenos.105

Sharing the spotlight with Pallas Athena, Klimt’s second female figure personifying the art of ancient Greece is, remarkably, the Girl from Tanagra (fig. 4.9). She is shown as a flesh-and-blood young woman in a dot-rosette patterned dress, with a mantle wrapped around her waist and a wreath in her hand, who is bending forward, perhaps to make a dedication. The Tanagra Girl’s inclusion, decorating an intercolumniation, in this monumental context underscores the lofty artistic significance then ascribed to the recently excavated little Greek terracotta figurines.106 Klimt, like Gérôme, was deeply inspired not merely by discoveries of nineteenth-century Greek archaeology, but especially by their fresh evidence for the surface colors and gilding employed in ancient Greek art.107

Figure 4.9: Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1861–1918), Girl from Tanagra: detail of Ancient Greece, 1890–91. Oil on canvas mounted on wall: intercolumniation of grand staircase colonnade, 90 1/2 x 31 1/2 in.). Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Image: CC-BY-SA-4.0.

Klimt’s Girl from Tanagra, while not mimicking specific terracottas in pose or details of dress, has the auburn hair and red lips attested on Tanagra figurines (fig. 4.7; cat. nos. 4, 7, and 10), enhancing this physical incarnation of a young ancient Greek woman who inspired the small antique artworks.108 In this painting, Klimt juxtaposes with Tanagra Girl an ancient bronze statuette showing the nude goddess of beauty Aphrodite (Venus) bending over to tie her sandal. This comparison surely alludes to the Girl from Tanagra’s own alluring feminine charms,109 including her provocative, loose long hair and smoky eyes, which make her a progenitor of famous powerful and erotic females from the artist’s later art-nouveau Gold Period.110

The second antiquity depicted here is a Greek vase shown standing on a marble base in the background—an enlarged reflection of an Athenian black-figure amphora of the late sixth-century BCE in the Vatican Museums. Its vase-painting depicts the Greek hero Herakles (Hercules), backed by his patroness the goddess Athena, confronting the multi-headed guard-dog, Kerberos (Cerberus), at the entrance to the Underworld, while the god Hades stands before his palace there, and his wife Persephone, the abducted daughter of Demeter, goddess of earthly fertility, sits inside.111 Herakles captured Kerberos and led the hound back to earth—a labor that symbolized this hero’s gaining immortality. Since then-known Tanagra figurines had generally been found in graves, Klimt’s choice of this Greek vase-painting has been held to indicate that “like Herakles, the Tanagra maidens had returned from the underworld.”112 Persephone was another rare mythological character able to return to earth. Significantly, Klimt omits Persephone from the detail of the vase-painting depicted, and his Girl from Tanagra obscures its Herakles. Visually taking the place of these ever-living characters emphasizes Tanagra Girl’s immortal status on Earth amid the international mania for Hellenistic terracotta figurines.

Artists and Tanagras in America

Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851–1938)

In late nineteenth-century America, the painter Thomas Wilmer Dewing, influenced by Whistler’s tonalism and Japonisme, became the country’s major practitioner of screen painting.113 In 1894–1895, Dewing traveled abroad to London and Paris, and, for several months, worked alongside Whistler in his London studio. There, Dewing executed the evanescent pastel on light brown paper Figure in Grey and Pink Drapery (cat. no. 43) depicting an introspective young woman wearing a Greek chiton. With one arm akimbo recalling the Titeux Dancer (cat. no. 1), the model’s pose has been likened to Tanagra figurines,114 and the pastel’s color should be. A departure from Dewing’s earlier female imagery, might this trendy antique allusion be associated with Whistler’s counsel?

At home, Dewing enjoyed the patronage of two wealthy Detroit-industrialists: Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919), who actively acquired Japanese screens and Whistlers, and Freer’s business partner Frank J. Hecker (1846–1927).115 Both of Dewing’s patrons collected Tanagra figurines in the 1890s, and Freer even employed Dewing as an agent to purchase figurines for him in New York City.116 Photographs show Tanagra figurines displayed in Hecker’s French-Renaissance-style Detroit mansion;117 in the Public Room, might a cast of the Titeux Dancer have stood on the mantel? Hecker’s Tanagra collection is considered the impetus behind a pair of tripartite folding screens he commissioned from Dewing in 1898 as decoration for his drawing room.118 The sole screen preserved intact, housed in its original Stanford White frame, at the Detroit Institute of Arts, is known as Classical Figures; it depicts three slender female figures in chiton-like dresses peopling an abstracted, misty, verdant landscape.119

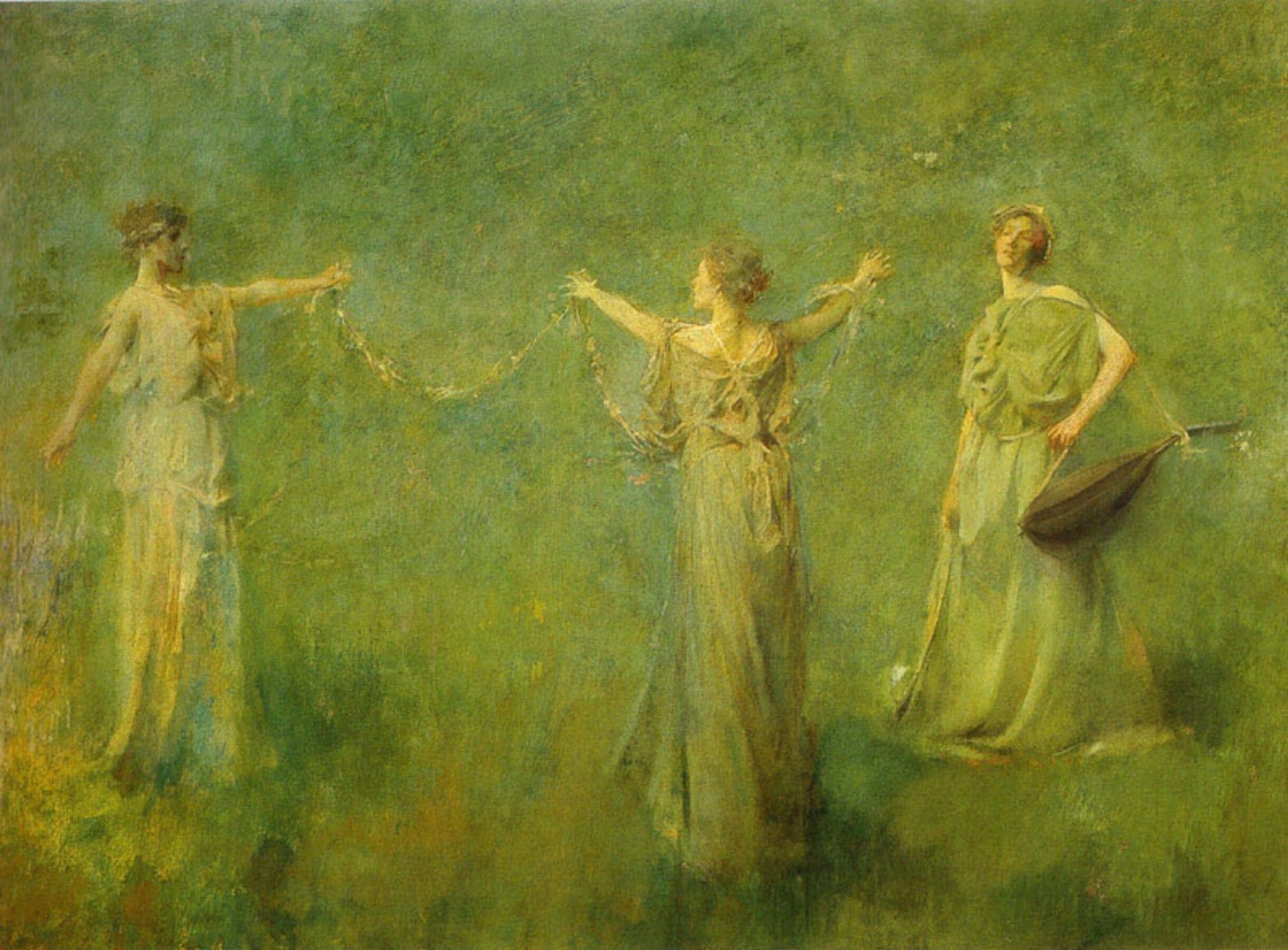

Dewing’s 1899 tonalist painting commissioned by Freer, The Garland (fig. 4.10), is likewise an abstracted landscape featuring several enigmatic female figures wearing chitons; two figures bear the titular floral garland with their arms extended—one shown in a front view and the other from the back—while the third carries a lute.120 A unique terracotta group from Tanagra (fig. 4.11), which is modeled fully in the round and depicts two comely young women dressed only in chitons and dancing with their arms extended,121 was acquired by the Louvre Museum in 1893. It strikes a chord with Dewing’s lithe, classicizing female figures. The Garland was intended as a gift for another tonalist landscape painter patronized by Freer, Dwight W. Tryon (1849–1925). Interestingly, Tryon happened to see this painting before knowing it would be gifted to him and wrote Freer his reaction: “Gee!! but it’s a corker. . . . One of the things that will live for all time with the Elgin marbles, with Tanagra—with all that is beautiful and uplifting.”122

Figure 4.10: Thomas Wilmer Dewing (American, 1851–1938), The Garland, 1899. Oil on canvas, 80 x 107.3 cm (31 1/2 x 42 1/4 in.). Private Collection. Image: Courtesy of the Art Renewal Center – www.artrenewal.org.

Figure 4.11: Two Girls Dancing, from Tanagra, Hellenistic, ca. 330–200 BCE. Terracotta with traces of polychrome, H. 17.8 cm (7 in.). Paris, Louvre Museum, CA 588. Image © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Bessie Potter Vonnoh (1872–1955)

At the turn of the twentieth century, a remarkably successful American female sculptor active in Chicago and then in New York, Bessie Potter Vonnoh (fig. 1.19), specialized in depicting women’s daily life primarily in bronze statuettes, inspired by the quotidian female imagery (fig. 3.18) of the American expatriate painter Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) and the trendy ancient Greek terracottas.123 Vonnoh’s distinctive textured and energetic surface handling was influenced by the preeminent modern French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840–1917), himself an avid antiquities collector, who praised Tanagra figurines highly.124 However, annoyed at critics’ association of her own small-scale works with the ancient terracotta figurines, Vonnoh initially denied knowing about them.125 Yet her now-renowned bronze group Day Dreams, which was modeled in 1898 and cast around 1906–1907, depicting two young women napping on a sofa with one reclining in the lap of the other, must immediately have recalled to viewers famous ancient Greek works in the British Museum, not only monumental Classical goddesses from the Parthenon’s East Pediment,126 but also a miniature Late Hellenistic terracotta group probably from Myrina, acquired in 1885, showing two female figures seated together on a draped couch.127 And Vonnoh’s Day Dreams was first exhibited in a lightly tinted plaster, perhaps associated with the nineteenth century’s awakening to the color of ancient sculpture afforded, in part, by Tanagra figurines.128

Another early work likewise counts among Vonnoh’s most famous, Girl Dancing, which was modelled in plaster in 1897 and cast in bronze around 1899 (cat. no. 46). This female figure is not archaeologically antiquizing, however: Believed to be dancing a quadrille, she wears a modified version of a classicizing high-waisted, Federal-era dress with a flowing skirt held out in her hands. Nonetheless, Girl Dancing, who enchantingly moves through the surrounding space, displays a kinship with Tanagra figurines by her very absorption in dance (see cat no. 1; fig. 4.11).129 Though Vonnoh’s creations are often around twice the height of Tanagras, the revered ancient figurines’ intimate size raised the esteem for small modern works like hers.130 And in the mid-twentieth century, Thompson associated Hellenistic terracotta figurines with now generally lost ancient prototypes in small bronze statuettes.131

For several years extending into the 1910s, Vonnoh became interested in working with terracotta—an impulse perhaps triggered by Tanagra figurines—and she had a kiln installed in her studio. The Fan (cat. no. 47), modeled around 1910, is Vonnoh’s best-known preserved terracotta statuette.132 It depicts a young woman with airbrushed facial features holding an open feather fan in her right hand; she wears a long V-necked dress with a cascading skirt that pools around her onto the work’s slab base. The Fan strongly evokes, but does not copy, ancient Tanagra terracotta female figurines, many of whom likewise carry fans (see figs. 2.1 and 4.4), though not feather fans.

In her later bronze works, including The Dance and The Scarf, both modeled around 1908, as well as In Grecian Draperies, modeled 1912 or 1913 and cast around 1914, Vonnoh did depict contemporary women wearing classically inspired dress loosely based on the ancient chiton.133 And her graceful statuettes bring to mind the Louvre Museum’s unique Tanagra group of chiton-wearing dancing young women (fig. 4.11) that may already have inspired Dewing (fig. 4.10). In an 1896 book, Maurice Emmanuel even endeavored to reconstruct ancient Greek dance using preserved works like the himation-clad Titeux Dancer (cat. no. 1).134 Modern artistic representations of female figures wearing flowing classicizing dress were especially related to the well-established adoption of such costume internationally in the realm of theater and dance. By the early twentieth century, the American Isadora Duncan (1877–1927) performed abroad and then also in the States wearing loose chiton-like garments often of diaphanous fabric, and she cited Tanagras as a source for her modern self-expression.135 In Parisian haute couture, the fashion house Maison Margaine, founded by Armandine Fresnais-Margaine (1835–1899), had debuted with a “Tanagra” dress in 1889. This streamlined draped Grecian garment, worn with updated underclothes, allowed contemporary women greater freedom of movement.136 By 1912, even a New York Times headline proclaimed that Parisian “Spring Styles will Adopt the Flowing Draperies of the Tanagra Statuettes.”137

Thomas Pollock Anshutz (1851–1912)

In 1909, the American realist painter Thomas P. Anshutz won the gold medal at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts with The Tanagra (fig. 4.12).138 In this 6.5-foot-tall painting, a smartly dressed woman wearing a towering hat admires a small collectible set atop a large, dark-marble pedestal: It is a terracotta figurine reflecting the Louvre Museum’s famous so-called Tanagra, the eight-inch-high Late Classical Athenian Titeux Dancer (cat. no. 1).139 The model, Rebecca Harbert Whelen (1877–1950), was Anshutz’s student at the Academy and the daughter of a trustee.140 The artist depicted her frequently between 1905 and 1910, beginning with The Incense Burner,141 which portrays Miss Whelen, wearing a resplendent black and gold evening dress, seated on a bench in front of the bronze or brass burner. The concocted settings here and in The Tanagra are formal but indeterminate. These paintings belong to a prominent genre of works depicting women, but symbolically titled after an object in the composition (as in cat. no. 47).142 In The Tanagra, the Greek figurine is the titular focal point. Here, Rebecca Whelen’s three-quarter-view pose with her left arm behind her back and the pale ecru color of her lovely, but conservative bowed and cinch-waisted day-dress echo the little image of the renowned himation-clad terracotta dancer; Anshutz’s composition likens the modern to the ancient conception of female beauty.143 And his painting thus reinforces a rarefied American ideal of its time.144

Figure 4.12: Thomas Pollock Anshutz (American, 1851–1912), The Tanagra, 1909. Oil on canvas. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 1912.1. Gift of the friends and admirers of the artist. Image: Public domain.

Elie Nadelman (1882–1946)

Works from the 1910s by the Polish Jewish American sculptor Elie Nadelman were destined to play a role in New York City’s beauty scene. Earlier, while residing amid the bohemian Polish community in Paris, from 1904, Nadelman created avant-garde, simplified and stylized works based on monumental Classical Greek sculpture. According to Barbara Haskell, “this return to classicism for inspiration was particularly appealing to Jewish artists because it bypassed the Renaissance and the Christian subject matter in which its art was steeped.”145 Despite suffering from antisemitism in Paris, Nadelman enjoyed great success exhibiting thirteen of his classicizing plasters, including nude statues of women, at Galerie E. Druet in 1909.146 He was then awarded another show in 1911 at London’s William B. Paterson Gallery, where all of Nadelman’s modern classical heads were purchased by the cosmetics magnate and art collector Helena Rubenstein (1872–1965),147 who was likewise an expatriate Polish Jew.

As a young woman, Rubenstein went to Australia, where she started her cosmetics business, and then established salons in London and Paris. With the onset of the First World War in 1914, Rubenstein left for New York and helped Nadelman move there too. She wanted to open a salon on Fifth Avenue, but Jews were not allowed in the building. Nonetheless, in 1915, Rubenstein set up her first New York City beauty salon nearby at 15 East 49th Street, and it was prominently decorated with Nadelman’s works.148 His sculptural group she had commissioned abroad showing women engaged in grooming and dressing activities (fig. 4.13) was installed in alcoves in the waiting room.149 Nadelman’s group, probably executed circa 1912 and later named The Four Seasons, consists of tall, sinuous, unglazed terracotta female figures, whose flowing draperies display fluted folds. Notably, the Rubenstein terracottas—this artist’s first dressed female images—though not painted, betray a new source of ancient inspiration, Tanagra figurines, which Nadelman said initially intrigued him when he saw the British Museum’s display during his London show.150 To Nadelman, modern sculpture inspired by these charming ancient female figures must have “seemed appropriate for a beauty salon.”151 Rubenstein believed Nadelman’s works, which henceforth always decorated her salons, evoked the timeless, classic ideal of female beauty achievable through her regimes and products. She had even changed her first name from Chaja (in Hebrew, Chay-ah, meaning to live) to Helena, thus becoming a namesake of ancient Greece’s most beautiful woman.152

Figure 4.13: Eli Nadelman (American, 1882–1946), The Four Seasons, ca. 1912, terracotta, H. 80 cm (31 1/2 in.). New York, New York Historical Society, 2001.223.1-4. Image © Courtesy the New York Historical Society.

Childe Hassam (1859–1935)

In the 1910s, Childe Hassam, the foremost American Impressionist, created his commercially successful New York Window series, showing women in interiors before windows frequently shown with closed curtains obscuring city views.153 In his Window painting of 1918, entitled Tanagra (The Builders, New York) (cat. no. 45), the curtains are parted, revealing men working on a skeletal skyscraper outside. According to Hassam,

Tanagra—the blonde Aryan girl holding a Tanagra figurine in her hand against the background of New York buildings—one in the process of construction and the Chinese lilys springing up from the bulbs is intended to typefy and symbolize groth—beautiful groth—the groth of a great city hence the sub-title The Builders, New York.154

Yet the painting’s young woman does not even look at the dynamic, male, urban realm outside.155 Recalling Anshutz’s earlier The Tanagra (fig. 4.12), the attention of Hassam’s model is likewise entirely focused on an ancient figurine.156 Her Tanagra features a svelte silhouette evoking an Aphrodite (Venus) (see cat. no. 10) more than an ancient human female clad in layers of Greek dress. However, this figurine’s coloration in greens and blues, which harmonizes with the picture’s Impressionist color scheme, may also evoke an ideal association of dressed Tanagras with the Louvre Museum’s still beautifully painted Dame en bleu (fig. 2.1).

Wearing a flowing, unstructured housedress perhaps mingling inspiration from Greek and Japanese costume, Hassam’s reflective blonde inhabits a fashionable interior featuring a large Japanese chrysanthemum screen behind her and a highly polished round mahogany table bearing a shallow porcelain bowl of flowers in the foreground. The painting’s assemblage juxtaposing Eastern and Western items is ultimately Whistlerian,157 but rather than the composition of a Japanese print, its restricted space evokes a Manhattan apartment.158 The mahogany table also appears in Hassam’s Maréchal Niel Roses of 1919 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, where the same blonde model, possibly Kitty Hughes, is seated contemplating that painting’s titular yellow flowers.159 The table was a prop in Hassam’s impressive long-term residence and studio in an artists’ cooperative at 130 West 57th Street.160

In his later work, Hassam ascribed to an artistic attempt to retain a traditional American ideal, rooted in the late nineteenth century, that involved depicting beautiful, pure, upper-middle-class white Anglo-Saxon Protestant women at home and at leisure, surrounded by tasteful decorations and furnishings—in a realm apart from men. Fueled by social anxiety brought about by massive immigration, a prototype for an “ideal Aryan type” came to be recognized in ancient Greek and Roman art.161 While Hassam’s Tanagra painting from the year after women won the right to vote in New York must have been a reassuring concoction for a conservative male audience, one can readily envision its Grecian, figurine-holding, blonde model as having been a customer at Helena Rubenstein’s nearby salon.

Conclusion

Significantly, the modern artworks influenced by these humble but charming ancient Greek terracotta figurines, which were mostly executed by male artists, depict exclusively female imagery. Some works show modern women observing female Tanagra figurines (figs. 4.2 and 4.12; cat. no. 45). Others show modern women dressed like female Tanagra figurines (cat. no. 14; figs. 4.3, 4.5, and 4.10). A few works represent women in the ancient world dressed like female Tanagra figurines (figs. 1.5, 1.6, and 4.9). Gérôme invented a modern monument in naked female form denoting the earth-shattering significance of the 1870 archaeological discovery of ancient terracotta figurines at Tanagra, Greece (fig. 4.8). Nadelman created alluring terracotta art figures (fig. 4.13) evoking ancient female Tanagras, destined to decorate a New York beauty salon. These diverse female depictions together demonstrate the enduring cultural dialogue engendered by Tanagra mania both abroad and at home.

-

The following people have aided my scholarship for this essay in various ways: Elizabeth Bartman, Joan R. Mertens, Annie Verbanck-Piérard, Seán Hemingway, Arthur Livenas, J. David Farmer, H. Alan Shapiro, and Eric Silver. In 1997, Stephen R. Edidin invited me to speak at the Dahesh Museum, N.Y., about Gérôme and female nudity; this topic piqued my interest in the influence of Tanagra figurines. A preliminary talk related to the present essay delivered at the 2020 Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America in Washington, D.C. was followed by expanded versions for the Cosmopolitan Club, N.Y., and the Department of Greek and Roman Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Special access to The Museum’s Onassis Library for Hellenic and Roman Art and Thomas J. Watson Library has facilitated my research. My heartfelt thanks go to the abovementioned individuals and institutions as well as to the curators of Recasting Antiquity for inviting me to participate in this exhibition catalogue and providing scholarly assistance. ↩︎

-

Dorothy Burr Thompson, “The Origin of Tanagras,” American Journal of Archaeology 70, no.1 (January 1966): 51–63, pls. 17–20 (also n. 131). ↩︎

-

Jaimee P. Uhlenbrock, “Coroplast and his Craft,” in The Coroplast’s Art: Greek Terracottas of the Hellenistic World, edited by Jaimee P. Uhlenbrock, 15–21 (New Paltz: College Art Gallery, The College at New Paltz, State University of New York and New Rochelle, N.Y.: Aristide D. Caratzas, 1990), 16–17; Arthur Muller, “La technique des coroplathes de Tanagra: De l’artisanat local à une industrie ‘mondialsée,’” in Tanagra: Mythe et archéologie (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2003), 171–74; Reynold Higgins, Tanagra and the Figurines (London: Trefoil Books: 1986), 66–69; Lucilla Burn and Reynold Higgins, Greek Terracottas in the British Museum, vol. 3 (London: British Museum Press, 2001), 18–20. ↩︎

-

Brigitte Bourgeios and Violaine Jeammet, “La polychromie des terres cuites grecques: Approche matérielle d’une culture picturale,” Revue Archéologique 69, no. 1 (2020), 3–28, esp. 6, 9–14, 21–26; Higgins, Tanagra and the Figurines, 69–70; Burn and Higgins, Greek Terracottas, 20; Uhlenbrock, “Coroplast and his Craft,” 18. ↩︎

-

See, recently, Vizenz Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, eds. Bunte Götter: Golden Edition: die Farben der Antike (Munich: Prestel, 2020). ↩︎

-

E.g., Hannelore Hägele, Color in Sculpture: A Survey from Ancient Mesopotamia to the Present (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013), esp. 252–265; Jennifer M. S. Stager, Seeing Color in Classical Art: Theory, Practice, and Reception from Antiquity to the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), esp. 7, 11, 14, 25–27, 43–44, 287; Brigitte Bourgeois and Violaine Jeammet, “Le paradoxes de l’invention de la polychromie au XIXe siècle,” in Couleurs: La Sculpture Polychrome en France 1850-1910, edited by Édouard Papet (Paris: Musée d’Orsay and Vanves: Éditions Hazan, 2018), 151–56. ↩︎

-

Mireille M. Lee, Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 90–95, 106–10, 107, fig. 4.11, 113–16, 230; R. J. Barrow, Gender, Identity and the Body in Greek and Roman Sculpture, prepared for publication by Michael Silk (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 51. ↩︎

-

Dillon, “Case Study III: Hellenistic Tanagra Figurines,” in A Companion to Women in the Ancient World, edited by Sharon L. James and Sheila Dillon (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 233–34; cf. Violaine Jeammet, “The clothes worn by Tanagra figurines: a question of fashion or ritual?” in Tanagras: Figurines for Life and Eternity: the Musée du Louvre’s Collection of Greek Figurines, edited by Violaine Jeammet, translated by Janice Abbott (Paris: Musée du Louvre and Valencia: Fundación Bancaja, 2010), 134–135 and Daniel Graepler, “Kunstgenuẞ im Jenseits? Zur Function und Bedeutung hellenistischer Terrakotten als Grabbeigabe,” in Bürgerwelten: Hellenistische Tonfiguren und Nachschöpfungen im 19. Jh, edited by Gerhard Zimmer and Irmgard Kriseleit (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preussischer Kulterbesitz and Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, 1994), esp. 43–49, 53–65. ↩︎

-

Burn and Higgins, Greek Terracottas, 20. ↩︎

-

Jeammet, ed., Tanagras, 87–88, cat. no. 57 (Violaine Jeammet). ↩︎

-

Léon Heuzey, “La danseuse voilée d’Auguste Titeux,” Bulletin de correspondence hellénique 16 (1892): 73–87. ↩︎

-

Jeammet, ed., Tanagras, 87–88, cat. no. 57 (Violaine Jeammet). ↩︎

-

Higgins, Tanagra and the Figurines, 163–68; Irmgard Kriseleit, “Fälschungen in der Berliner Sammlung,” in Bürgerwelten: Hellenistische Tonfiguren und Nachschöpfungen im 19. Jh. (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preuẞischer Kulturbesitz, Antikensammlung and Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1994), 59–69; Arthur Livenais, Un petit people de pacotille: la collection de fausse terres cuites du musée du Louvre. Mémoire de recherche. (Paris: École du Louvre, 2020); and Valentin Veldhues, “Salonstücke – Terrakotta-Manie und Fälschungen,” in Klasse und Masse: Die Welt Griechischer Tonfiguren, edited by Valentin Veldhues and Agnes Schwarzmaier (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preuẞischer Kulturbesitz and Petersburg, Michael Imhof Verlag, 2022) 31–33 and 34–41, cat. nos. 6–9. ↩︎

-

Édouard Papet, “Variations sur la Danseuse Titeux,” in Tanagra: Myth et archéologie (Paris: musée du Louvre and Réunion de musées nationaux, 2003), 54. ↩︎

-

E.g., Bourgeois and Jeammet, “Le paradoxes de l’invention de la polychromie,” 154; Roberta Panzanelli, ed., The Color of Life: Polychromy in Sculpture from Antiquity to the Present (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum and Getty Research Institute, 2008), 167, cat. no. 35 (David Saunders). ↩︎

-

Reinhard Kekulé, Griechische Thonfiguren aus Tanagra (Stuttgart: W. Spemann, 1878). ↩︎

-

Curtis, Tanagra Figurines (Boston: Houghton, Osgood and Company, 1879). ↩︎

-

León Heuzey, Le figurines antiques de terre cuite du Musée du Louvre, engraved by Achille Jacquet. (Paris: Ministère de L’Instruction Publique et des Beaux-Arts and V. A. Morel, 1883). ↩︎

-

See the classic study by T. J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and his Followers, Rev. edition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999) and George Moore, “Degas: The Painter of Modern Life (November 1890),” in The Painter of Modern Life: Memories of Degas by George Moore and Walter Sickert, edited by Anna Gruetzner Robins, 21–66 (London: Pallas Athene, 2011). ↩︎

-

Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life,” in The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, by Charles Baudelaire, translated and edited by Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon and Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society Publishers, 1964), 1–40. ↩︎

-

This Degas notebook is inventoried as Bibliothèque Nationale, Dc 327d reserve, Carnet 11; see Theodore Reff, The Notebooks of Edgar Degas: A Catalogue of the Thirty-eight Notebooks in the Bibliothèque Nationale and Other Collections, 2 vols, vol. 1 (New York: Hacker Art Books, 1985), 18, 49; see also, Theodore Reff, “Degas’s Copies of Older Art,” Burlington Magazine 105, no. 723 (June 1963): 245–46, 247, no. L. 39, and 248, no. A.716. ↩︎

-

Reff, Notebooks of Degas, vol. 1, 52, nb. 6, p. 20. For this early terracotta group’s unusual technology, see Jeammet, Tanagras, 80–81, cat. nos. 45 and 47 (Violaine Jeammet). ↩︎

-

Reff, Notebooks of Degas, vol. 1, 52, nb. 6, p. 16. For the female figurine (Louvre Museum MN 575), see Besques, Louvre Catalogue Raisonné des Figurines et Reliefs en Terre-cuite, vol. 4, pt. 2 text: 44, pl. 16, c; vol. 4, pt. 2 plates:16, c; and Jeammet, ed., Tanagras, 206, cat. no. 173. ↩︎

-

Joseph Vattier de Bourville (1812–1854), who led excavations at Cyrene, purchased figurines for the Louvre Museum; see Besques, Louvre Catalogue Raisonné des Figurines et Reliefs en Terre-cuite, vol. 4, pt. 2 text: 19; and Jeammet, ed., Tanagras, 204–07, cat. nos. 171–76 (Juliette Becq). See also Reff, Degas, 72 and 311, n. 102, on Degas’s copying and Cyrene. ↩︎

-

Simone Besques, Musée du Louvre Catalogue Raisonné des Figurines et Reliefs en Terre-cuite Grecs, Étrusques et Romains, vol. 4, pt. 2 text: 48, pl. 19, d; vol. 4, pt. 2 plates: 19, d. ↩︎

-

Theodore Reff, “Copyists in the Louvre, 1850-1870,” Art Bulletin 46, no. 4 (December 1964): 557. The ancient source was recognized by Roseline Bacou, Musée du Louvre: La donation Arï et Suzanne Redon (Paris: Ministère de la culture, Éditions de la Réunion des Musées nationaux, 1984), 69, no. 109; John Rewald, “Odilon Redon,” in Odilon Redon, Gustave Moreau, Rudolphe Bresdin (New York: Museum of Modern Art and Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, distributed by Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1961), 16, imprecisely describes Redon as having “studied the delicate shapes of Tanagra figurines” at the Louvre Museum, but his copying was before figurines were discovered at Tanagra. ↩︎

-

Violaine Jeammet, “Un certain goût pour les Tanagras: du XIXe siècle à l’Antiquité,” in Tanagras: De l’objet de collection à l’objet archéologique. Actes du colloque organisé par le musée du Louvre à la Bibliothèque nationale de France le 22 novembre 2003 (Paris: Picard and Musée du Louvre, 2007), 33. ↩︎

-

Academia di Francia a Roma, Degas e l’Italia (Rome: Villa Medici and Fratelli Palombi, 1984), chronology of Degas’s time in Italy, 255–60. ↩︎

-

Vide text supra at n. 11. ↩︎

-

P. A. Lemoisne, Degas et son oeuvre, vol. 2 (Paris: P. Brame et C.M. de Hauke aux Arts et métiers graphiques, 1946–49. Reprint, New York: Garland Publishing, 1984), 18, no. 39, 19, fig. 39; Sotheby’s, Impressionist and Modern Art Day Sale, November 6, 2015 (New York, 2015) lot no. 341. ↩︎

-

Jean Sutherland Boggs, Degas (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1996), 45; and Christopher Lloyd, Edgar Degas: Drawings and Pastels (London: Thames & Hudson, 2014), 131, emphasize multiple viewpoints of the same pose in preparatory drawings for Degas’s wax sculpture Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, ca. 1878–1881, Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, 1999.80.28, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.110292.html. See esp., Three Studies of a Dancer in Fourth Position, 1879–1880 (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1962), 703, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/14970/three-studies-of-a-dancer-in-fourth-position. ↩︎

-

See Richard Kendall, Degas Dancers (New York: Universe of Art and Vendome, 1996). ↩︎

-

Waxes: Suzanne Glover Lindsay, Daphne S. Barbour, and Shelley G. Sturman, Edgar Degas Sculpture (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art; distributed by Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 152–249, cat. nos. 19–41; Jean-Luc Martinez, ed., Corps en Mouvement: La Dance au Musée (Paris: Musée du Louvre and Éditions du Seuil, 2016), illustrating dance movement in art, features the Titeux Dancer (cat. no. 1), 39–41, cat, no. 1, and a Degas dancer in bronze, Paris, Musée d’Orsay R.F. 2073, 132–33, cat. no. 55. ↩︎

-

See Musée Marmottan Monet, Henri Rouart 1833-1912: L’Oeuvre peinte (Paris: Musée Marmottan Monet and Éditions Gallimard, 2012); and Musée de la Vie romantique, Au coeur de l’Impressionnisme: la famille Rouart (Paris: Musée de la Vie romantique and Paris musées, 2004). ↩︎

-

Jean Sutherland Boggs, “Mme Henri Rouart and Hélène by Edgar Degas,” Bulletin of the Art Division of the Los Angeles County Museum 8, no. 2 (Spring 1956): esp. 13–15; Boggs, Portraits by Degas, esp. 67–68. ↩︎

-

Boggs, “Mme Henri Rouart,” 15, fig.1; Boggs, Portraits by Degas, 67 and pl. 122. ↩︎

-

Boggs, “Mme Henri Rouart,” 14, muses, “perhaps Hélène had wrapped herself in a shawl in order to resemble the figurine.” In the 1880s, Degas compared art by Honoré Daumier (1808–1879) to Tanagras; see Reff, Degas, 71–72. ↩︎

-

Cf. Dorit Schäfer and Astrid Reuter, eds., Sehen Denken Träumen: Franzosische Zeichnungen aus der Staatlichen Kunsthalle Karlsruhe (Karlsruhe: Staatlichen Kunsthalle Karlsruhe and Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2018), 178, cat. Entry (Dorit Schäfer); Boggs, “Mme Rouart,” 15–17; and Boggs, Degas, 68. ↩︎

-

Papet, “Variations sur la Danseuse Titeux,” 54. ↩︎

-

Boggs, Degas, 67; Götz Adriani, Degas: Pastels, Oil Sketches, Drawings, translated by Alexander Lieven (New York: Abbeville Press, 1985), 381; Solange Thierry, “Henri Rouart,” in Au coeur de l’Impressionnisme: la famille Rouart (Paris: Musée de la Vie romantique and Paris musées, 2004), 23–24. ↩︎

-

Reff, Degas, 145, 319, n. 172. ↩︎

-

Boggs, “Mme Henri Rouart,” 15–17; Jean Sutherland Boggs, Drawings by Degas (Saint Louis: City Art Museum of Saint Louis, 1966), 190–92, cat. no. 125; Édouard Papet, “De l’objet archéologique aux babioles de luxe,” in Tanagra: Myth et archéologie (Paris: musée du Louvre and Réunion de musées nationaux, 2003), 39; Däubler-Hauschke and Brunner, ed., Impressionismus und Japanmode, 124–25, cat. no. 12; Ann Dumas and David A. Brenneman, Degas and America: The Early Collectors (Atlanta: High Museum of Art and New York: Rizzoli, 2000), 200, cat. no. 60 (Mary Morton), but mistakenly identified as a sketch for the unexecuted oil portrait. ↩︎

-

Musée Marmottan Monet, Henri Rouart, 46–47, cat. no. 6 (Jean-Dominique Rey). ↩︎

-

In a letter of October 16, 1883, to Henri Rouart in Venice: Reff, ed. And trans., The Letters of Edgar Degas, vol. 1 (New York: The Wildenstein Plattner Institute, Inc.; distributed by University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2020): 328–29, no. 202, with 329, n. 2, likened by Reff to Titian portraits; for the English translation see vol. 3: 75–76, no. 202. ↩︎

-

Louvre Museum S 1664; Musée du Louvre, Tanagra: Mythe et archéologie (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2003), 180–82, cat. no. 125, acquisition: “ancient fons” (old funds), also cat. no. 126 (Violaine Jeammet). ↩︎

-

Boggs, “Mme Henri Rouart,” 16. ↩︎

-

Marc Gerstein, “Degas’s Fans,” Art Bulletin 64, no. 1 (March 1982): 106–107, 117; Claudia Däubler-Hauschke, “Japanrezeption bei Degas und Whistler. Eine Annäherung,” in Impressionismus und Japanmode; Edgar Degas, James McNeill Whistler, edited by Claudia Däubler-Hauschke and Michael Brunner (Überlingen: Städtische Galerie and Petersberg, Germany: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2009), esp. 15; and Däubler-Hauschke and Brunner, ed., Impressionismus und Japanmode, 151–52, cat. no. 43 (Christian Berger). ↩︎

-

Gerstein, “Degas’s Fans,” 109–10. ↩︎

-

Suzanne Singletary, “James McNeill Whistler: A Conduit between France and America,” in Whistler to Cassatt: American Painters in France, edited by Timothy J. Standring (Denver: Denver Art Museum and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022), 82; Ayako Ono, Japonisme in Britain: Whistler, Menpes, Henry, Hornel and Nineteenth-century Japan (London: Routledge Curzon, 2003), esp. 41, 58–66; Gerstein, “Degas’s Fans,” 106–07; see also Laurel Lyman, The Influence of Japonisme on the American Impressionists and their Circle, 1893-1915. PhD diss. (City University of New York, 2004. Ann Arbor: UMI Microform 3115270, 2004), 215–16. ↩︎

-

Ono, Japonisme in Britain, 140; Franco Russoli, Degas (New York: Rizzoli, 2005), 172–75, chronological table. ↩︎

-

See Julia Atkins, “Ionides Family,” The Antiques Collector (June 1987): esp. 90–91; Ayako Ono, Whistler and Artistic Exchange between Japan and the West: After Japonisme in Britain (London: Routledge, 2023), 47; Julia Ionides, “The Greek Connection—The Ionides Family and their Connections with Pre-Raphaelite and Victorian Art Circles,” in Pre-Raphaelite Art in its European Context, edited by Susan P. Casteras and Alicia Craig Faxon (Madison, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1995), 168; and Charles Harvey and Jon Press, “The Ionides Family and 1 Holland Park,” Journal of the Decorative Arts Society 1850 – the Present 18 (1994): esp. 3–4; and 5, figs. 7–8, 6–7, for the antiquities room’s mantle designed to display Aleco’s Tanagras; see also fig. 1.7 above. ↩︎

-

For the Ionides’ presumed early collecting see Katharine A Lochnan, The Etchings of James McNeill Whistler (Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984), 152; Katharine A. Lochnan, Whistler’s Etchings and the Sources of His Etching Style, 1855-1880 (New York: Garland Publishing, 1984), 212; and Ionides, “Greek Connection,” 161. Marcus B. Huish, “Tanagra Terracottas,” The Studio 14 (1898): 101, mentions “Mr. A. Ionides being on the spot” when figurines were found. ↩︎

-