For James McNeill Whistler and his nineteenth-century peers, the word Tanagra conjured the image of a small terracotta figurine from Hellenistic Greece, typically depicting an elegantly draped woman, naturalistically modeled and enlivened with paint, perhaps veiled or wearing a wide-brimmed hat, and holding a fan or a floral garland. As Linda Merrill and Beth Cohen explore in their contributions to this catalogue, the word, and the ancient objects it evoked, not only revolutionized the nineteenth-century perception of Greek art, now recast as something modern, vibrant, and accessible in both demeanor and scale, in sharp contrast to the monumental public marbles that defined the prevailing image of classical art at the time, but it also quickly came to embody a certain aesthetic mood or style that gave classicizing form to the contemporary female body and to contemporary notions of ideal femininity. In this sense, the nineteenth-century reception of Tanagra figurines and the diffuse deployment of their image in art and fashion was not so far removed from their ancient function as models and modelers of ideal Greek womanhood.

The figurines themselves were produced across the Hellenistic world but take their modern name from the site of Tanagra in Boeotia in northern Greece, a leading center of production in antiquity. Significant numbers were first discovered in the 1870s, buried inside tombs.1 Although representations of men, children, the elderly, and gods are also known (see e.g., cat. nos. 6 and 10), most extant Tanagras depict adult, mortal women, identifiable as such by their costumes, accessories, and poses.2 Decorated with precious pigments, and in some instances also with gold, they give tantalizing insight into both the original appearance of large-scale painted sculpture and the dressed bodies of real women in antiquity (fig. 2.1). Indeed, as Linda Merrill demonstrates, it was the extensive survival of Tanagras’ polychrome decoration, as well as their intimate, seemingly feminine character and scale, that excited nineteenth-century collectors, artists, and scholars, who interpreted them as bourgeois ornaments for the home and the tomb, the ancient precursors of so many Victorian gewgaws.

Figure 2.1: Statuette of a Draped Woman, known as the “Lady in Blue,” Greek, ca. 325–300 BCE. Terracotta, pigment, gilding. 12 6/8 x 4 1/2 x 3 5/8 in. (32.5 x 11.5 x 9.2 cm). Louvre Museum. MNB 907. Image © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Yet, the archaeological evidence suggests that Tanagra figurines in fact most likely served as votives in both funerary and sanctuary contexts,3 implying significance beyond passive decoration or fashion archive. Hollow cast using two-piece molds (cat. no. 2), they were infinitely replicable, easily mass-produced, and more affordable than figurines made from metals or stone, facilitating widespread distribution across potentially broad social strata. Examples have been excavated in tombs alongside jewelry, mirrors, and perfume vessels, indicating a feminine context, and they seem to have been especially popular grave gifts for children, where they perhaps embodied the adult roles of wife and mother that the deceased child would now no longer achieve.4

Others have been found in sanctuaries dedicated to deities connected with marriage, sex, and fertility, or else with the passage from childhood to adulthood, including Aphrodite, Artemis, Demeter, and Kore.5 At the town of Priene, Tanagras have been documented in domestic contexts, again alongside objects like loom weights and cooking utensils that are conventionally associated with women, thus prompting scholars to question whether they were made and purchased first as votives or were personal possessions later repurposed.6

Sheila Dillon has argued that the ways in which many of the female Tanagras are depicted—lavishly draped, veiled, and accessorized—defines them as both elite and ideally beautiful, and places them explicitly within the world of religious rituals and public festivals, that is, “the world of women on the public stage.”7 Indeed, as Dillon observes, it can be no coincidence that Tanagra figurines first emerged as a class of objects in Athens at the same time as marble portrait statues of women, which often share the same poses and costumes, begin to be dedicated in the city as votives to celebrate women’s public and religious roles as priestesses (fig. 2.2).8 This suggests a functional as well as formal relationship between the two types of sculpture, positioning female Tanagras as miniature monuments to Hellenistic women’s participation in, and contribution to, the ritual life of the city, the family, and the home.9

Figure 2.2: Large Herculaneum Woman, Greek, 1st century CE. Marble. H: 78 in. (2.0 m). National Archaeological Museum of Athens, 3622. Image: CC BY-SA 4.0.

This in turn opens the way for the Tanagra figurine to function as the epitome of femininity, defining women’s ideal public roles and social identities by offering a model of appearance and behavior. Certainly, if we consider girls to be one primary audience, as the funerary evidence would suggest, then these Tanagras become terracotta Barbies, presenting an aspirational female physique, costume, demeanor, and role for their young viewers to grow into.10 Taking this as its starting point, this essay nuances our understanding of how Tanagra figurines defined and diffused an image and idea of Greek womanhood by drawing attention to the materiality of the statuettes alongside their iconography,11 and by considering the significance of pigment and of clay, and of the processes of molding, casting, and painting, as metaphors for the construction and conceptualization of the female body and of female identity in the Greek world.

This returns agency to terracotta as a medium and to molding as a technique, both easily dismissed as nothing more than cheap alternatives to other materials and processes.12 But by placing the Tanagras in conversation with an ancient literary discourse that defined women as manufactured objects, both hollow container painted surface, a materialist approach such as this also creates space for the exploration of female subjectivity and the potential for self-fashioning through the same processes of adornment, draping, shaping, and molding that characterized both Tanagra production and dominant patriarchal views of female identity in the Greek world.13

Shaping the body

As has been widely discussed by Dillon and others, in terms of their costume, pose, and activities, the female Tanagras embody a socially determined ideal of mortal femininity, in contrast to divine, that is defined by the competing expectations of modesty, beauty, restraint, and sexual allure.14 In the Greek world, it was considered a woman’s duty to be desirable to attract a husband and bear children. A wife was consequently required to maintain standards of beauty, cultivation, and refinement.15 Sartorial elegance was also a marker of privileged status.16 Yet, male anxiety around women’s unchecked sexuality as a threat to male honor meant that modesty in dress and behavior was simultaneously promoted as a virtue; women’s adornment was always viewed as potentially treacherous. For this reason, laws restricted the color, transparency, and cost of garments that women could wear during religious rituals, while treatises warned women against wearing gold, jewels, and imported silk to protect their reputations.17

It should not surprise us, therefore, that in modeling an image of the ideal Greek woman, Tanagra figurines play with contrasting ideas of visibility and invisibility, and of propriety and ostentation, making the contradictory demands that society placed on women integral to the form and fabric of her body. This is most apparent in terms of costume and pose. Most female Tanagras are conventionally dressed according to contemporary fashion. A long, belted tunic (chiton) covers most of the feet beneath a lightweight mantle (himation) that is wrapped around the body and held in place with the arms, often covering the hands (cat. no. 4 is representative).18 Many pull their mantle over their hair (e.g., cat. no. 3), and some wear a face veil (tegidion) (e.g., cat. no. 8, here folded over the crown of the head like a kerchief);19 if heads appear uncovered, hair is always carefully coiffed and controlled.20 Arms are often crossed over the torso or raised to the chin in a conventional gesture that signals modest restraint.

As a result, these women appear swaddled beneath their voluminous drapery, their bodies concealed and constricted in a way that was deemed appropriate for public appearances, especially at religious festivals,21 but that simultaneously embodied the desired feminine ideals of modesty, propriety, and submissiveness that endowed the respectable wife with ideal beauty.22 And yet, at the same time as it obscured the body, the volume of fabric worn by Hellenistic women, finely pleated, meticulously layered and draped, and brightly colored with expensive dyes, attracted the eye, distinguished the wearer from others, and signaled her wealth and prestige. So, too, did the sophisticated comportment required to control and move elegantly within it.23 The care with which the makers of these figurines delineated the textures of different textiles, evoking the transparency of fine Coan silk or Egyptian linen, colored with paint made from the same costly pigments that dyed the fabrics themselves (cat. no. 6), suggests that the ways in which dress made the wearer visible and desirable was of equal importance to the expression of elite female identity as was the performance of modesty.24

Even the poses work to bring the body beneath the fabric to the fore. One representative terracotta found at Tanagra itself, now in the Louvre (cat. no. 3), is shown with lowered gaze, clutching her mantle tightly over her head and across her torso with her right arm, which is raised beneath the cloak to her chest. She grips her skirt and the loose folds of the mantle with her left hand, held at her waist in a way that nevertheless accentuates the tilt of her hips and the curve of her right thigh. Another terracotta from ancient Myrina in Asia Minor, now also in the Louvre, even lifts her skirts and extends her body into a sensuous contrapposto curve, with one hip thrust languorously to the side (cat. no. 9). As Sarah Blundell notes, in almost every instance in which a woman is shown clutching at her clothes on Athenian vases, the gesture “carried intimations of eroticism.”25 The same is true here: even as they seemingly attempt to shield themselves from the gaze of onlookers, these figurines pull their drapery tight across hips, breasts, bellies, and thighs, effectively sculpting the body in a way that emphasizes its physical desirability. Indeed, their poses mimic the hipshot coquetry of the Aphrodite of Knidos, the famous cult statue of the goddess created by the Greek sculptor Praxiteles in the fourth century BCE, whose disingenuous attempts to shield her nudity with her arms instead directed her viewer’s desirous gaze precisely towards what was not meant to be seen (fig. 2.3; also cat. 10).26

Figure 2.3: Statuette of the Aphrodite of Knidos, Greek, 3rd–2nd century BCE. Marble, 9 5/8 x 3 1/16 x 2 11/16 in. (24.5 x 7.8 x 6.9 cm). Walters Art Museum, 23.98. Image: CC BY-SA 4.0.

By evoking the Knidia, the Tanagras’ body language hints at the fertility and sexual allure of the respectable wife, and of the pleasures of removing the drapery that signified her virtuous reserve.27 At the same time, they remind their female viewer that only adornment offers mortal women Aphrodite’s charm.28 But in the case of the Tanagras, of course, there is no body beneath the cloth; they are completely hollow, thanks to the process by which they were made.29 These figures are their drapery, making tangible the prevailing Greek notion that the mortal female body was a clothed body, or rather, that the dressed and adorned body was woman’s natural state.30 Pandora, the first woman of Greek myth, provides the paradigm.

Forthwith [Hephaistos] the famous Lame God molded clay in the likeness of a modest maid, as the son of Kronos purposed. And the goddess bright-eyed Athene girded and clothed her, and the divine Kharites and queenly Peitho put necklaces of gold upon her, and the rich-haired Horai crowned her head with spring flowers. And Pallas Athene bedecked her form with all manners of finery. Also [Hermes] the Guide, the Slayer of Argos, contrived within her lies and crafty words and a deceitful nature at the will of loud thundering Zeus, and the Herald of the gods put speech in her. And he called this woman Pandora (All-Gifts), because all they who dwelt on Olympos gave each a gift, a plague to men who eat bread.31

In the version told by the Greek poet Hesiod (thought to be active around 700 BCE), Pandora comes into being through the act of dressing, so that she is one and the same with the finely worked garments and jewelry with which she is adorned (fig. 2.4).32 This is, in effect, to reduce Pandora and all women that come after her to decorated surfaces,33 which for Hesiod and so many other Greek writers was to define woman as both highly crafted and deeply deceptive.34 Pandora’s beautifully wrought drapery and ornaments are as much a marker of her inherent craftiness as are her cunning words. Indeed, Greek and later Roman anti-cosmetic rhetoric consistently presented women’s adornment as a deceptive art, closely and negatively associated with artificiality, to the extent that authors frequently likened women’s bodies to luxury goods and manufactured objects, including vessels and woven textiles, objectifying the female by highlighting the constructedness and superficiality of her image.35

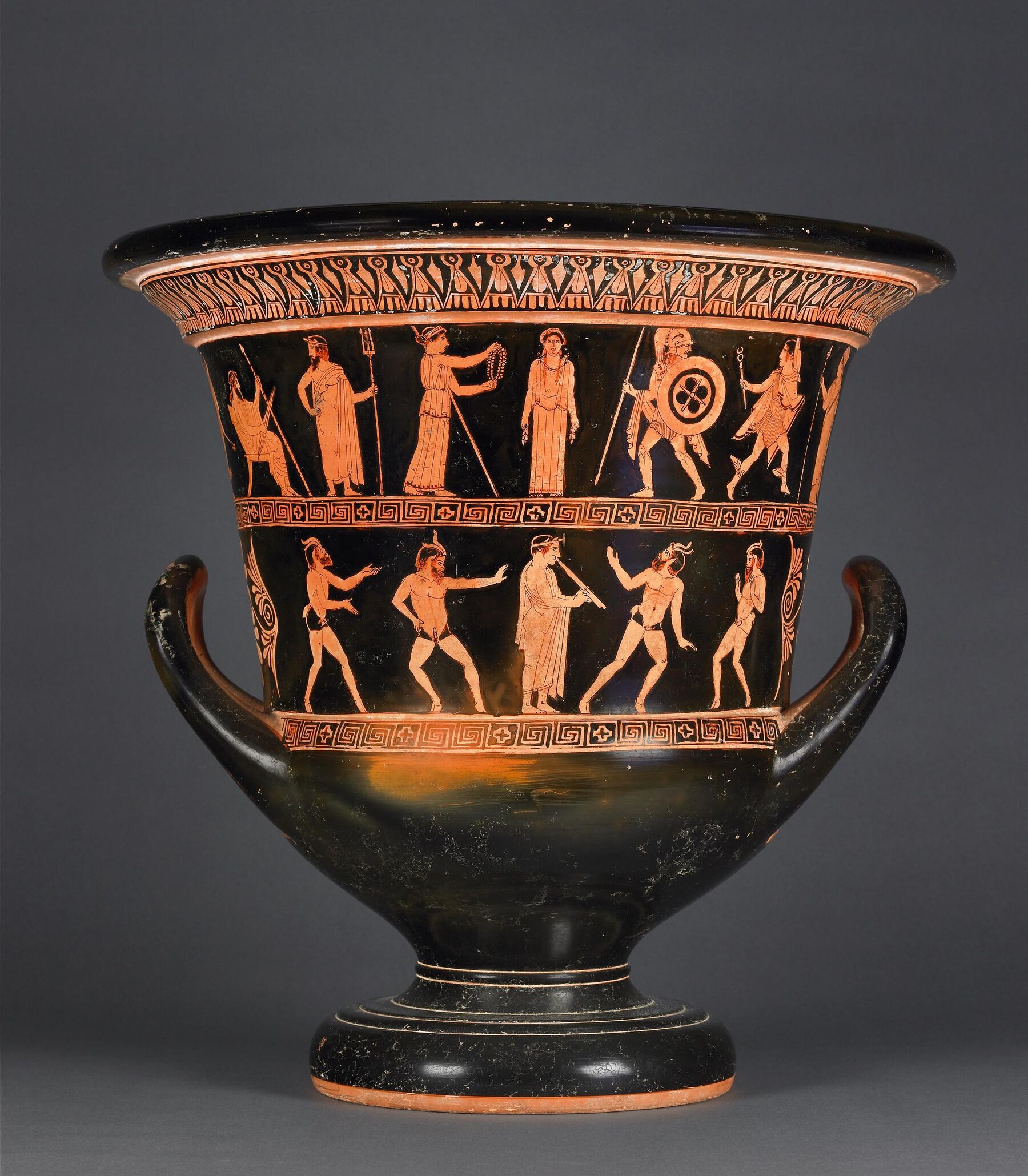

Figure 2.4: Red-Figure Calyx Krater with the Creation of Pandora, attributed to The Niobid Painter. Greek, Athenian, 460–450 BCE. Terracotta. H: 19 in. (49 cm). British Museum. 1856,1213.1. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Such analogies point to the potential gap between surface and substance that adornment might open, at the same time as suggesting woman’s interior emptiness, which, to the Greek mind, made her both a vehicle for reproduction and an insatiable glutton for luxury and sex.36 Tanagras, of course, make this metaphorical hollowness literal by virtue of their being cast from two-piece molds. But they also make it visible: almost all figurines have a square or circular opening in the back, which was ostensibly to prevent the terracotta from exploding by releasing moisture and hot air during the firing process (fig. 2.5). Yet, the typical size of these openings is approximately one inch in height, which is much larger than is needed to vent air from inside a terracotta sculpture. It has been suggested that the holes may also have provided access to the interior of the figurines to facilitate the process of connecting the separately cast parts from the inside. In any case, one consequence of the enlarged size of the openings is that they draw attention to the figurine’s emptiness as well as to its facture, making both intrinsic features of the idealized female body.

Figure 2.5: Statuette of a Draped Woman (reverse view), Greek, ca. 300–250 BCE. Terracotta, 9 11/16 x 3 7/8 x 2 in. (24.6 x 9.8 x 5.1 cm). Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University. Carlos Collection of Ancient Art, 1984.15. Image © Bruce M. White, 2014.

That Pandora should, like the Tanagras, also be molded from clay only reinforces her status as an artwork. Clay is the original stuff of creation used to make mankind in Sumerian, Egyptian, and Greek mythological traditions,37 and retains its status as the archetypal artist’s medium throughout Roman histories of artistic production. Indeed, for the Roman historian Gaius Plinius Secundus (Pliny the Elder, ca. 23/24–79 CE), the origins of all art are dependent on it. We are told that the first portrait modeled in clay was made by a Greek tile-maker, Butades of Sikyon (thought to be active ca. 600 BCE), who created a likeness of the young man with whom his daughter was in love by pressing clay onto the surface of a wall on which she had traced his silhouetted profile.38 This model was reportedly preserved in the Nymphaeum in Corinth until the Roman general Lucius Mummius sacked the city in 146 BCE, which was itself a critical moment in Rome’s own telling of its history of encounter with Greek art.39

Pliny goes on to relate how Butades used this new technique to make terracotta antefixes in the shape of faces to adorn the pediments of temples, a tradition supposedly exported to Italy in the seventh century BCE by Demaratos of Corinth, father of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, the first king of Rome.40 In Italy at this time, clay was also used to create cult statues of gods, confirming its historical significance as a key medium in the development of three-dimensional figurative art.41 Indeed, Pliny is careful to stress how clay also undergirds the work of major Greek artists such as Lysistratos, brother of the celebrated sculptor Lysippos, who was the first to model sculptures in clay before casting them in bronze to better capture a faithful likeness.42

Pliny’s discussion of clay as an artist’s medium is ultimately concerned with establishing the boundaries of morally viable cultural production in the new Roman world of empire, which threatened, with its expanded boundaries, infinite resources, and ever-more capacious categories for wealth, to push everything into luxuriousness.43 Where luxury represented an abuse of nature and a profligate waste of resources,44 clay, by contrast, was a material that could be extracted from the earth without endangering it, unlike quarrying for marbles or precious metals, and that did not increase the value of the objects it was used to create; likewise, its original association with temple decoration and the depiction of cult images ensured its moral value.45 For our purposes, though, Pliny’s discussion also helps us to understand how clay as a material was inextricably bound in the ancient mind to the idea of original composition, lifelike representation, and the touch of the artist’s hand, and was also synonymous with the development of three-dimensional figurative art in history as well as in myth.

To make a body from clay, then, was in many ways to promote its status as handmade artwork—something rendered tangible in the many terracottas that preserve the fingerprints of their maker (fig. 2.6).46 But it was also to engage with a literary discourse that frequently ascribed the same physical properties of clay, namely its malleability and the ease with which it receives impressions, to the female body. According to the philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BCE), the female of any species is “softer, quicker to be tamed, more receptive to handling, and readier to learn” than the male,47 characteristics we might collectively categorize as being more easily susceptible to outside forces, both physical and mental.48

Figure 2.6: Statuette of a Draped Woman with fingerprints embedded in the clay (detail), Greek, ca. 320 BCE. Terracotta, pigment. 8 1/8 x 2 1/2 x 3 1/16 in. (20.6 x 6.4 x 7.8 cm). Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University. Gift of the Christian Humann Foundation, 1986.19.2. Image © Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University.

In texts by other male writers, women’s flesh is considered spongier, more fluid and more permeable than men’s,49 and more in need of binding and shaping. So, the Greek physician Soranos of Ephesos (b. 98 CE), writing under the Roman Empire, states that all newborns need careful swaddling in order to “mold every part according to its natural shape,” but that girls should be bound tighter across the chest and more loosely around the loins to achieve the ideal female form.50 As adults, Roman women might further manipulate the shape of their bodies by bolstering hips, corseting stomachs, and even stitching cork into the soles of their shoes,51 suggesting how the female body remained malleable and open to change, even if only—or especially—in appearance.

That molding itself should be considered a female act is reinforced by the language of pregnancy and reproduction found in the same medical and philosophical texts. The Greek word matrix can mean both “uterus” and “mold,” a synonymy exploited in the Timaeus by the philosopher Plato, who imagines the womb molding the fetus into shape as it develops. Indeed, the potential for a womb to be like a mold is even made tangible in the prevalence of mold-made terracotta uteri dedicated as votives across Italy from the fourth to the first century BCE (see fig. 2.7).52

Figure 2.7: Group of votive uteri, probably Roman, ca. 200 BCE–200 BCE. Terracotta. Max: 5 13/15 x 2 1/2 x 2 3/16 in. (14.8 x 6.3 x 5.5 cm). Science Museum, Sir Henry Wellcome’s Museum Collection, A636082. Image © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum, London via CC BY-SA 4.0.

Plato’s theorization of how phenomenal objects come into being and change state likewise imagines a maternal space—the so-called Receptacle—in which phenomena appear, disappear, and receive new form.53 Verbs of molding, impressing, and modeling define Plato’s concept of the Receptacle, as do gendered notions of pregnancy.54 In this way, human reproduction becomes analogous to processes of mechanical mark-making and serial production. But we might imagine a viewer of a Tanagra figurine understanding the reverse to be true, too: cast from a mold that was itself cast from a hand-modeled prototype, then shaped and incised with tools, these terracottas make reproduction through replication and craft integral to the fabrication and function of the female body,55 while at the same time embodying the common literary trope that likened women to vessels and reduced them to their wombs.56 Those figurines that show draped women holding swaddled infants make even more explicit the conceptual link that is so deeply rooted in the Greek imagination between women’s hollow clay bodies and their capacity for reproduction (cat. no. 7).

Indeed, a parallel metaphor common in Greek literature equated women’s bodies to earth, which was considered the quintessential womb,57 ready to be plowed and sown. So, we are told in the Timaeus that the male seed is sown upon the womb “as upon plowed soil,”58 while the Athenian marriage agreement, made between the bride’s father and her new husband, was probably sealed with the formula, “I hand over this woman to you for the plowing of legitimate children.”59 Not only does this reduce woman to a clay womb, a container for offspring,60 at the same time as reiterating the clay-like softness and permeability of her flesh, but such metaphors of husbandry once again center the importance of cultivation—in the sense of both taming and refining—to the production of the female body and of female identity in the Greek world.61

This helps us to think about Pandora’s clay fabric as critical to a gendered reading of her body, and hence also any female body, as both artwork and womb/mold, the handmade prototype from which all women are cast.62 This in turn suggests the potential for every female Tanagra to be a miniature Pandora, made of earth and adorned with finery. If we accept that any female viewer of a Tanagra figurine saw herself reflected in its image, dressed as she may have been dressed or as she aspired to be seen, then this opens the way for every woman to see herself as Pandora, too. Our contention in this essay is that, for a female viewer of Tanagra figurines, to see herself as Pandora may in the end have been empowering rather than limiting.

Crafting a look

The suggestion that women required shaping and then cultivating through adornment is a trope later pushed to an extreme by the Roman poet Ovid (b. 43 BCE), who likens women’s adorned bodies to a series of raw materials that are crude by nature but made elegant by artistry.63

The statues of industrious Myron that now are famous

Were once dead weight and hard matter;

In order to make a ring, first gold is crushed;

The clothes that you wear were once filthy wool;

When it was made, your jewel was rough: now it is a noble gem,

On which a nude Venus wrings out her spray-drenched hair.64

Here, Ovid’s woman is not just equated to the gemstone she wears but also to the sensuous depiction of Venus engraved on it. The implication is that every woman needs work if she is to become civilized and fulfill the role of wife and mother that society demands. But by working on her appearance, she is contrived—nothing more than a shimmering image carved on the surface of a polished stone, concealing a dank, earthy, and hollow interior.65

Ovid’s analogy also justifies the emphasis placed in this essay on the potential for female viewers in antiquity to see themselves reflected in the images of women that they encountered—in both material and form—and for Tanagras therefore to be miniature mirrors and models for the women who looked at them. Even the Tanagras’ painted surfaces suggest a material as well as visual correspondence between viewer and figurine. Most Tanagras were covered with a ground layer of white clay such as kaolinite, which created a smooth surface that would bind well with applied paint, and might even be burnished to add shine.66 Women’s faces were also frequently coated with a foundation layer composed of different clays and chalks that aimed to achieve a smooth, pale complexion, which was a much-desired indicator of social status,67 and at the same time reinforces the potential for women’s bodies to be clay-like in their materiality.

According to ancient written sources, the most popular preparation was cerussa, a mixture of vinegar and lead white,68 which was also a common ingredient in paints used to color the faces of female Tanagras.69 White clay marl from the island of Melos, known as melinum, was likewise used to make white paint and to give a pale sheen to women’s complexions.70 Analyses of white pigments used in surviving samples of Roman period cosmetics reveal common use of calcite and gypsum.71 Similarly, chalk dust (creta) was used in antiquity both to brighten the complexion and to make sealings, which carried the impressions of intaglio-carved signets, like Ovid’s spray-drenched Venus, suggesting how the female face could be similarly shaped and impressed with a new, more seductive look.72 Taken together, we might think of women sculpting their faces into plaster masks before painting them with added color.73

As Kelly Olson notes, the literary sources indicate that rouge was the next most prominent cosmetic applied to women’s faces in antiquity.74 Roman authors mention red ochre (rubrica) and red chalk as common ingredients.75 Like white lead, the former was also frequently used to create the red paints used for Tanagras and other painted surfaces such as wall paintings, including the billowing drapery of cat. no. 6 and the lips of cat. no. 5.76 Likewise, soot, ashes, and lamp black were used as kohl to outline the eyes and darken the brows,77 just as carbon black was the preferred ingredient for black paint.78 As mentioned previously, the materials used to color the vibrant costumes of Tanagra figurines were often also used to dye the real fabrics worn by Hellenistic women, including cinnabar, red ochre,79 madder lake,80 and Tyrian purple made from the shells of the Murex snail.81

The figurine of Nike Phainomeride (Nike of the Visible Thigh) excavated in a tomb in Myrina and acquired by the Louvre in 1883 (cat. no. 6), wears a diaphanous pink peplos (a robe with a distinctive overfold) that has been carefully colored with a diffuse layer of pink-mauve paint composed of madder mixed with lead white and calcium phosphate, applied over a layer of red ochre. Bands of lead white decorate the lower edge of the dress, delineated by thin lines of yellow ochre.82 The effect here is not only to recreate the iridescent sheen of fine layered silks, as worn by real women, but also to suggest movement, enhanced by the luminosity of the pigments and the play of light on their surface. On some Tanagras, such as the so-called Lady in Blue (fig. 2.1),83 the application of gilding to the borders of draped mantles likewise replicates the use of gold thread in the embellishment of real textiles.84

Even the binders that were mixed with the pigments to make paint, as well as the varnishes used to protect and embellish the finished surfaces of the Tanagras, find parallels in ancient cosmetics. Both are rare to survive but were likely composed of animal or vegetable gums, egg, and vegetable resins,85 all of which are listed as ingredients in the ointments and face masks women wore to smooth and polish their complexions. To purify the face, Pliny recommends a wash of egg white,86 or a skin cream made from the jelly of a bull’s calf bone,87 while Ovid offers four recipes for face packs that promise to make a woman’s face “shine smoother than her own mirror,”88 including gum arabic,89 frankincense, and myrrh.90

It has long been recognized that the application of varnishes to polychrome surfaces in antiquity aimed to enliven the painted image by contrasting matte areas with shiny and so creating opportunities for light-play and the suggestion of movement.91 This was to satisfy the dominant aesthetic of poikilia, a term used variously in Greek literature to describe shimmering or dappled things and that conveys the spectacle of intricately worked, polychrome, and multi-textured surfaces.92 But where the application of surface polish to a Tanagra figurine stimulated the senses through the play of light and suggested movement, effectively breathing life into the terracotta body, like another Pygmalion’s statue,93 it is clear from the written texts that to make a woman’s complexion glossy was to reverse Pygmalion’s fantasy and turn her into a glittering artwork, or, in Ovid’s words, a shimmering image reflected in a mirror.94

Molding the self

Where it is easy to understand Tanagra figurines as miniature facsimiles of the women who may have dedicated them in temples or with whom they were buried, literature’s emphasis on the “make” in “make-up” encourages us to turn the relationship on its head and instead consider the female viewers of Tanagras as facsimiles of the figurines. They, too, were massaged and molded into ideal form, prepared, painted, and polished with lotions and pigments, and finally adorned with costly textiles and jewelry, posed and artfully manipulated to attract the eye of the viewer and to suggest the desirability of the body beneath—a body prepared for marriage and motherhood, to be exchanged as a commodity between father and husband just like any other artwork. As we have seen, this synonymy is encouraged not just by the representation of contemporary dress and the suggestion of familiar and idealized contexts of behavior and action, but in the suggestive correspondence of the Tanagras’ material and manufacture to cultural ideas about women’s physical ontology—their earthy, malleable flesh and mold-like capacity for reproduction—as well as in the common ingredients of their painted decoration. We might even think about the process of mechanical reproduction used to create the Tanagras, by which multiple identical figurines could be cast from the same two-piece mold (fig. 2.8), dressed in uniform and with anonymous faces, as analogous to the cultural production of a homogenized and collective female identity that occluded individual character in favor of ideal social roles (namely mother, daughter, wife, priestess), and that was both achieved and understood through adornment.95

Figure 2.8: Three statuettes made from the same mold. Greek, ca. 330–200 BCE. Terracotta, pigment, 8 9/16 x 3 7/16 x 2 3/8 in. (21.7 x 8.7 x 6.1 cm); 10 x 3 5/8 x 2 7/8 in. (25.4 x 9.2 x 7.3 cm); 8 13/16 x 3 1/16 x 2 3/4 in. (22.3 x 7.7 x 6.9 cm). Louvre Museum, MNB 452, MNB 494, MNB 559. Image © RMN Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

If adornment, then, was the process by which women made themselves into artworks to be consumed by male viewers, then the Tanagras should be understood as promoting adornment’s capacity to objectify the wearer. The figurines typically stand on a low rectangular base (cat. no. 4), ostensibly to stabilize the hollow form, but also to underscore the terracotta’s status not as a representation of a real woman but as an objet d’art, or better, as a representation of a woman turned into an artwork—like Pygmalion’s lover or another Pandora. This potentially positions the female viewers of Tanagra figurines as both willing participants in and products of a male-imposed system of cosmetic control that sought to satisfy male desire and diminish women’s agency by indicating their inherent falseness.96 Sarah Blundell has posited in her discussion of scenes of female adornment on Athenian vessels, which were typically used by women as containers for make-up, perfume, or jewelry, that female viewers had learned to be pleased by images of themselves that were pleasing to men and that reproduced dominant patriarchal views of women’s roles,97 and subsequently sought to model their bodies in their likeness. If Tanagras were designed according to male ideals about women’s appearances, and were in turn produced by male artisans,98 then this also opens the door for them to appeal to male viewers as well.

Recent scholarship, however, has argued for a more positive view of adornment, seeing it less as a process of objectification and more as a means of positive self-construction. Olson has promoted a view of women’s adornment as “a deliberate act, indicative of both female agency and a knowledge of the power of the visual, by which a woman could communicate the self to others and infuse the self with a sense of esteem and legitimacy.”99 She suggests that we need to view women as knowledgeable social actors who used adornment as a “creative way by which to exercise a means of authority and influence, a means to become sexually and economically visible and attract attention.”100 For Leslie Shumka, the capacity to design and maintain a look through makeup, jewelry, and dress was one of the few ways in which Roman women could express themselves, and constituted a different kind of craft, a means of shaping one’s own identity.101 She notes the prevalence of representations of toiletry articles on Roman women’s tombstones as evidence for the ways in which women’s personal ornamentation was viewed positively by women as a vehicle of self-expression.102

This encourages us to look at the Tanagras as comparable embodiments of Hellenistic women’s capacity to manipulate their own image and through it their identity. Like the tombstones that Shumka discusses, the presence of so many Tanagras in what were likely female graves implies a positive association between these idealized images of femininity and the women who viewed them. Certainly, the evocation of women’s public presence and religious roles, as suggested by the Tanagras’ dress, opens space for female celebration of women’s social visibility and their participation in the civic life of the community. We have also seen how women’s manipulation of their drapery and their body language could be a means of commanding attention, arousing desire, and communicating wealth on a public stage.103

But where we might view this as evidence of women’s acceptance of the narrow remit of their public visibility, which was limited by function and controlled by dress, Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz, in her discussion of Athenian vases, has pointed to the ways in which images of women that promoted an ideal look or behavior contributed to women’s sense of themselves as a community and subsequently to the establishment of a female culture that prioritized female viewers (and hence also female makers) of female bodies, to the exclusion of the male.104

Tanagras embody this potential for a self-supporting and self-regarding community of women cast in each other’s image.105 Unlike the life-size marble statues of women with which they were clearly in conversation, displayed publicly and seen by both men and women, the contexts within which the terracottas were viewed implies a more intimate and perhaps exclusively female audience. It is unlikely that men would have frequented the sanctuary spaces in which the female Tanagras were dedicated, while the figures’ small-scale restricted how many people could look closely at any one time, facilitating women’s private contemplation of the female form and inviting personal communion between image and viewer.

If we accept the gendered associations of molding as a technique, then we might also view Tanagras as female-made, at least conceptually. This is further encouraged when we consider that molds were sometimes cast directly from other terracotta figurines, establishing family-trees of mother, daughter, and sister casts, which evokes Hesiod’s description of Pandora propagating the race of women, seemingly independently of men.106 But the depiction of a female potter on the so-called Caputi Hydria, an Athenian red-figure hydria attributed to the Leningrad Painter, now in the Torno collection in Milan,107 provides tantalizing evidence for the real existence of female artisans working with clay. This encourages us to consider the possibility that at least some Tanagras were made by female coroplasts, and making Gerome’s fantasy of a female-run Tanagra workshop less fanciful than it might seem (see fig 1.5).108

Although we may in truth never know the gender of the artisans that made Tanagras in antiquity, reframing these figurines as female-made, female-viewed, and self-generated gives new agency to their clay medium and to the perceived clay-like bodies of real women. Rather than the passive product of an artist’s hand, they become autochthonous, “born from the earth,” like Erichthonios, the mythical first king of Athens, and so are intrinsically capable of endlessly recasting themselves and their appearances. We have already hinted at how the poses that the Tanagras strike and the ways that they manipulate their dress enacts a kind of body modulation, so that they sculpt their form by pulling, gathering, and draping their garments into new shapes that echo the erotic curves of the Knidia. That this is so often done with hands and arms that are enclosed within the folds of the fabric that they handle (e.g., cat. nos. 3, 4, 5) reiterates that this is an interior, autonomous action, a moment of self-craft that encourages the Tanagras’ female viewers to feel empowered by the opportunities that adornment presented to engage in self-production.109 If we take Sarah Blundell’s lead and recognize the erotic frisson of images of women shown clutching their clothes,110 then we might go one step further and even see the Tanagras as embodiments of the pleasures of self-expression through adornment, which becomes a form of self-love once we prioritize women as both the makers and the viewers of the adorned female body.

Certainly, without a male audience, posing like Aphrodite becomes a way of declaring one’s desirability to oneself, recalibrating the misogynistic view of adornment as a means of cultivating the wayward female body instead into a model of self-care. And it is worth noting here that many of the same ingredients that were used for women’s cosmetics and for the decoration of Tanagra figurines were also used as therapeutic medicines in antiquity.111 Even clay was a popular remedy for various conditions. For example, Pliny notes that red clay from Lemnos was used as a red pigment but could also be applied as a liniment or ingested to counteract snake bites and other poisons, treat sore eyes, and even to control menstruation.112 The clay was reportedly sold in sealed packages, formed into a tablet known as a sphragis, or “seal,” and impressed with a signet bearing the image of the goddess Artemis, underscoring a material and functional relationship between medicine, cosmetics, pigments, and objects of adornment,113 and implying an intimate connection to the female body.

Indeed, as Amy Richlin notes, the properties of cosmetics, medicines, poisons, and even magic were frequently conflated in antiquity as comparable crafts that aimed at “a certain kind of control over the body and its surroundings.”114 Unsurprisingly, for most male commentators, this reiterated the danger of the cosmetically enhanced woman, whose constructed appearance was not only untrustworthy but also potentially harmful. But from a female perspective, we might instead see the therapeutic possibilities of cosmetics as a means of soothing and bolstering the self, either physically or psychologically. With the medicinal uses of clay in mind, Tanagras’ draped and painted terracotta bodies go one step further and promote adornment as a means of protecting and healing the body, giving it a shinier, more powerful, and more vital appearance.

Unmaking the self

Tanagra figurines, then, not only offered an image of ideal femininity to their female viewers, but also a model for its construction that was contingent on the material possibilities of clay and paint as substances intimately connected to the female body in the Greek imagination, and of molding as a method that was evocative of pregnancy and reproduction. If the female body was a dressed body, then Tanagras suggest possibilities for draping and adorning with jewelry and cosmetics to be a means of constructing and even caring for the self in a way that was empowering both in private and in public.

Produced in multiples and perhaps viewed serially, they also established a female look that enabled women to find pleasure in their capacity to satisfy the male gaze, but more importantly, also to find pleasure in their capacity to shape a self that was visible, desirable, self-generated, self-sustaining, and able to define women’s sense of themselves as a community. They also invite an embodied form of viewing. By endlessly repeating the same gestures of clutching, grasping, and manipulating their drapery, Tanagras encourage their viewers to imagine the feel of different fabrics and the sensation of moving within billowing skirts, in a way that reiterates the pleasures of adornment, both material and experiential.

But some Tanagras offer a riposte to this model of female self-production through dress and demeanor. The so-called Titeux Dancer, perhaps the most iconic Tanagra of the nineteenth century,115 discovered in Athens in 1846 and widely referenced by numerous artists of the period, exemplifies a popular class of terracottas depicting veiled dancers that were found across the Mediterranean from the early fourth century BCE (cat. no. 1).116 She is shown mid-pirouette, with her thin drapery falling loosely away from her body in tumbling waves that swirl around her ankles; her garment is so delicate and her movement so rapid that it washes over breasts, stomach, and legs like water, so that she appears almost naked despite being fully draped. In fact, she looks more like representations of maenads, the mythical female followers of Dionysos, god of ecstasy, abandon, and altered states, who symbolized women’s wild, unfettered nature, and were typically shown in various states of undress (fig. 2.9).

Figure 2.9: Marble relief with a dancing maenad. Roman, ca. 27-14 CE. Marble. HL 56 5/16 in. (143 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art, 35.11.3. Image: Public Domain courtesy of the Met’s Open Access Policy.

Unlike her demure terracotta sisters, therefore, this Tanagra offers an alternative to the strict control of dress and deportment that conventionally defined women’s social standing. Hers is a body instead striving to free itself from its drapery, and in so doing, redefines adornment as a potentially de-civilizing force. It has been argued that these veiled dancers depict female worshippers engaged in specific ritual practice, which may, indeed, have been associated with Dionysos and other ecstatic deities. They may also be professional dancers, perhaps performing the baukismos, a spinning dance of Ionian origin that is defined in the ancient sources by its grace, intricacy, and sensuality. According to Julius Pollux, a Greek writer of the second century CE, the baukismos was “a dainty type of dance that liquefies the body,”117 while the cultic dances associated with Dionysos and others offered similar possibilities for the dissolution of physical and metaphysical boundaries and for release from all constraint. This hints at how the fluid dress worn by the Titeux Dancer and other terracotta dancers might instead promote the potential for adornment to take the wearer beyond even the limits of self-production: to be a means not only of shaping oneself into ideal form, but of liberating the self entirely from society’s strictures and becoming formless.118 Defined by their ever-malleable materiality, in this way Tanagra figurines come to symbolize models of both manufacture and emancipation for the Greek female body and its female viewers.

-

Production of so-called Tanagra style figurines is generally considered to have lasted from 330 to 200 BCE, with Tanagra and Thebes as major centers of manufacture. The style originated, however, in Athens in the third quarter of the fourth century BCE; see Jeammet 2010, 62–69. The literature on Tanagra figurines is lengthy. Key publications include Reynold A. Higgins, Tanagra and the Figurines (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986); Violaine Jeammet, Tanagra: mythe et archéologie : Musée du Louvre, Paris, 15 septembre 2003-5 janvier 2004 : Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, 5 février-9 mai 2004 (Réunion des musées nationaux ; Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, Paris, Montréal, 2003); Violaine Jeammet, Tanagras: Figurines for Life and Eternity: the Musée du Louvre’s Collection of Figurines (Valencia: Fundación Bancaja, 2010); Sheila Dillon, “Case Study III: Hellenistic Tanagra Figurines,” in A Companion to Women in the Ancient World, edited by Sharon L. James and Sheila Dillon (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2012), 231–234. For a review of their discovery and reception, see Linda Merrill, “‘Darlings of Victorian Taste’: Tanagras & the Nineteenth Century.” ↩︎

-

Rosemary J. Barrow, Gender, Identity, and the Body in Greek and Roman Sculpture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 49. It has even been suggested that the existence of so many draped female figurines in museum collections today is as much due to the tastes of nineteenth-century collectors as to the preponderance of female subjects in antiquity; see Lucilla Burn and Reynold A. Higgins, Catalogue of Greek Terracottas in the British Museum, vol. 3 (London: Trustees of the British Museum, 2001), 20. See also essays in this volume by Linda Merrill and Beth Cohen. ↩︎

-

Violaine Jeammet, “The clothes worn by the Tanagra figurines: a question of fashion or ritual?,” in Jeammet Tanagras (2010), 134. ↩︎

-

Ibid.,160–161. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 160–161. ↩︎

-

Rosemary J. Barrow, Gender, Identity, and the Body in Greek and Roman Sculpture, 61. See also Alexandra Harami, “Les fouilles de sauvetage des nécropoles de l’antique Tanagra,” in Tangras. De l’objet de collection à l’objet archéologique. Actes du colloque musée du Louvre/Bibliothéque Nationale de France (Paris, 22 Nov. 2003), edited by Violaine Jeammet (Paris: Picard, 2007), 68. ↩︎

-

Dillon, “Case Study III: Hellenistic Tanagra Figurines,” 233. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

On women’s increased presence in public life during the Hellenistic period, see Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones, “House and veil in ancient Greece,” British School at Athens Studies, 2007, Vol. 15, Building Communities: House, Settlement and Society in the Aegean and Beyond (2007), 256–257; see also Sarah B. Pomeroy, Women in Hellenistic Egypt. From Alexander to Cleopatra (New York: Schoken Books, 1984), ↩︎

-

Terracotta dolls with articulated limbs were also popular grave gifts. Just like Barbie, these dolls encouraged little girls to cultivate adult toilette habits by playing dress-up with contemporary-styled clothing and jewelry; Leslie Shumka, “Designing women: the representation of women’s toiletries in funerary monuments in Roman Italy,” in Roman Dress and the Fabrice of Roman Culture, edited by Jonathan Edmondson and Alison Keith (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008), 174. ↩︎

-

Much scholarship on Tanagras has been concerned with typology and iconography, that is, on pose, drapery style, and attributes, useful for determining questions of production, chronology, and social significance. Little attention has been given to the materiality of Tanagra figurines, beyond scientific analyses of their’ clay fabric and surface decoration, often for the purposes of determining production techniques and workshop locations. See for example, Brigitte Bourgeois, “Arts and crafts of colour on the Louvre’s Tanagra Figurines,” in Jeammet, Tanagras (2010), 238–244. ↩︎

-

Indeed, the perceived ordinariness of terracotta was part of what appealed to the Victorian viewers of Tanagras; see Linda Merrill, “‘Darlings of Victorian Taste’: Tanagras & the Nineteenth Century.” ↩︎

-

I am inspired here by Sue Blundell and Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz’s discussion of adornment scenes in Attic vase-painting; Sue Blundell and Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz, “Women’s bodies, women’s pots: adornment scenes in Attic vase-painting,” Phoenix, Vol. 62, No. 1/2 (Spring/Summer 2008), 115–144. ↩︎

-

Dillon, “Case Study III: Hellenistic Tanagra Figurines,” 88. ↩︎

-

Eve D’Ambra “Nudity and adornment in female portrait sculpture of the 2nd century AD,” in I, Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome, edited by Diana E. E. Kleiner and Susan B. Matheson (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1996), 102. See also Diana E. E. Kleiner and Susan B. Matheson, “Introduction,” in I, Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome, edited by Diana E. E. Kleiner and Susan B. Matheson, 13. ↩︎

-

Dillon, “Case Study III: Hellenistic Tanagra Figurines,” 100. ↩︎

-

Sheila Dillon, The Female Portrait Statue in the Greek World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 100, citing Riet van Bremen, The Limits of Participation: Women and Civic Life in the Greek East in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods (J.C. Gieben, Amsterdam, 1996), 142–144. ↩︎

-

This new style of dress may have developed in this period specifically for portrait statues of women; see Dillon, “Case Study III: Hellenistic Tanagra Figurines,” 5. ↩︎

-

See Llewellyn Jones, “House and veil in ancient Greece,” (2007). ↩︎

-

On loose hair as a sign of unrestrained morals in adult women, see Molly M. Levine, “The gendered grammar of ancient Mediterranean hair,” in Off with Her Head!: The Denial of Women’s Identity in Myth Religion, and Culture, edited by Howard Eilberg-Schwartz and Wendy Doniger, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 76–130. ↩︎

-

Llewellyn-Jones suggests female veiling was commonplace in ancient Greece; see Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones, Aphrodite’s Tortoise: The Veiled Woman of Ancient Greece (Swansea: Classical Press of Wales, 2003). Dillon argues for a specific ritual context; Dillon, “Case Study III: Hellenistic Tanagra Figurines,” 231. See also Nathalie Martin, “Terracotta veiled women: a symbol of transition from nymphe to gyne,” in Hellenistic and Roman Terracottas. Monumenta Graeca et Romana, Vol. 23, edited by Giorgos Papantoniou, Demetrios Michaelides, and Maria Dikomitou-Eliadou (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 223–236. ↩︎

-

Dillon, "Case Study III: Hellenistic Tanagra Figurines,"133; see also Judith Sebesta, The World of Roman Costume (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), 128. ↩︎

-

Dillon, “Case Study III: Hellenistic Tanagra Figurines,” 233. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Sue Blundell, “Clutching at clothes,” in Women’s Dress in the Ancient Greek World, edited by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (Swansea: Classical Press of Wales, 2002), 162. ↩︎

-

According to Pseudo-Lucian (Amores 17), the Knidia was so attractive that young men even attempted to have sex with the statue. ↩︎

-

As Dillon observes, concealing the body beneath layers of sumptuous fabric, constantly manipulated to hint at the physical form beneath, was also a stratagem deployed by prostitutes in ancient Greece. This underscores the potential ambiguity of female adornment and increased female visibility, which made women’s bodies hard to categorize; Dillon, The Female Portrait Statue in the Greek World (2008), 100. ↩︎

-

Ruth Allen, “A cultural history of engraved Roman gemstones - their material, iconography, and function,” Ph.D. dissertation (University of Cambridge, 2016), 93. ↩︎

-

See Merrill, “‘Darlings of Victorian Taste’: Tanagras & the Nineteenth Century.” ↩︎

-

Dillon, “Case Study III: Hellenistic Tanagra Figurines,” 60. ↩︎

-

Hesiod, Works and Days 54–80 (trans. Evelyn-White). See also Hesiod, Theogony, 570–89. ↩︎

-

Or, as Jean-Pierre Vernant states, “Pandora’s clothing is integrated into her anatomy” Jean-Pierre Vernant, Mortals and Immortals, edited by Froma I. Zeitlin (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), 38. See also Judith L. Sebesta, “Visions of gleaming textiles and a clay core: textiles, Greek women, and Pandora,” in Women’s Dress in the Ancient World, edited by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (Duckworth: Classical Press of Wales, 2002); and Amy Lather, Materiality and Aesthetics in Archaic and Classical Greek Poetry (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021), 104-108. ↩︎

-

Following Nicole Loraux, “Herakles: the super-male and the feminine,” in Before Sexuality: The Construction of Erotic Experience in the Ancient Greek World, edited by David M. Halperin, John J. Winkler, Froma I. Zeitlin (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), 30. ↩︎

-

Verity Platt, Facing the Gods: Epiphany and Representation in Graeco-Roman Art, Literature and Religion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 112. ↩︎

-

For discussion of the trope, particularly in literature, see Alison Sharrock, “Womanufacture,” Journal of Roman Studies 81, 36–49; also Kelly Olson, Dress and the Roman Woman: Self-presentation and Society (London and New York: Routledge, 2008); Eve D’Ambra, “Nudity and adornment in female portrait sculpture of the 2nd century AD,” in I, Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome, edited by Diana E. E. Kleiner and Susan B. Matheson, 101–115; Victoria Rimell, Ovid’s Lovers: Desire, Difference and the Poetic Imagination (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 1; Eric Downing, “Anti-Pygmalion: the praeceptor” in Ars Amatoria, Book 3, Helios 17 (1999), Maria Wyke, “Woman in the mirror: the rhetoric of adornment in the Roman world,” in Women in Ancient Societies: An Illusion of the Night, edited by Léonie J. Archer, Susan Fischler, Maria Wyke (New York: Routledge, 1994), 141–146, who notes that objects of adornment themselves decorated with scenes of adornment “all connect the adorned female body intimately with craftsmanship” (144). ↩︎

-

See Eve D. Reeder, “Women as containers,” in Pandora: Women in Classical Greece (Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 1995), 195–199. This is articulated by Hesiod’s extended simile comparing women to drone bees “reaping the labor of others into their bellies” (Theogony 595–600). ↩︎

-

On Prometheus, see Pseudo-Apollodoros Bib. 1.7.1. For the Sumerian myth of Enki fashioning man, see The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, c.1.1.2. ↩︎

-

Pliny, Natural History, (henceforward NH) 35.43. For discussion of the passage, and Pliny’s attitude to clay, see Verity Platt, “Earth, terracotta, and the plastic arts,” in Wonder and Wakefulness: The Nature of Pliny the Elder, exh. cat., edited by Verity Platt and Amy Wieslogel (forthcoming). ↩︎

-

See, for example, Miranda Marvin, The Language of the Muses: the Dialogue Between Roman and Greek Sculpture (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2008). ↩︎

-

Polybius 6.11a.7. See John North Hopkins, Unbound from Rome: Art and Craft in a Fluid Landscape, ca. 650-250 BCE, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024). ↩︎

-

Pliny NH 35.45. ↩︎

-

Pliny NH 35.44. He likewise cites Varro’s praise of the first-century sculptor Pasiteles, who we are told never completed any work in bronze without first modeling it in clay; NH 35.45. He concludes from this that the art of modelling in clay is more ancient and therefore more venerable than working in bronze. ↩︎

-

On Pliny and luxury, see Eugenia Lao, “Luxury and the creation of a good consumer,” in Pliny the Elder: Themes and Contexts, edited by Roy Gibson and Ruth Morello (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 35-56; and Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, “Pliny the Elder and man’s unnatural history,” Greece and Rome 37, no. 1, 80–96. ↩︎

-

See Emanuela Zanda, Fighting Hydra-Like Luxury: Sumptuary Regulation in the Roman Republic (London: Bloomsbury Publishing), 1; Mark Bradley, Colour and Meaning in Ancient Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 88. ↩︎

-

Sarah Blake McHam, “‘We penetrate the earth’s innards and search for riches’: Pliny’s hierarchy of materials and its influence on the Renaissance,” Material World. NIKI Studies in Netherlandish-Italian Art History 15 (21 May 2021), 95. ↩︎

-

On clay as the embodiment of authentic creativity in eighteenth-century Europe, see Lauren R. Cannady, “The validation of terracotta in eighteenth-century image and text,” Athanor 25 (2007): 77–83. ↩︎

-

History of Animals 8 (9): 1.608 ↩︎

-

On Aristotle’s biology, see Robert Mayhew, The Female in Aristotle’s Biology: Reason or Rationalization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 99. ↩︎

-

See, for example, Euripides, Hippolytos, 730–731. See Ellen D. Reeder, “Women as containers,” 199; Jean-Baptiste Bonnard, “Male and female bodies according to ancient Greek physicians,” Clio: Histoire, Femmes et Societes, Vol. 37 (2013), 21–39. ↩︎

-

On Gynecology 2.15. For discussion of swaddling practice and its representation in Hellenistic and early Roman material culture, see Emma-Jane Graham, “The making of infants in Hellenistic and early Roman Italy: a votive perspective,” World Archaeology 45, no. 2 (2013): 215–231. On swaddling as a means of shaping the newborn body according to culturally defined and gendered aesthetics, see Leslie Shumka, “Designing women: the representation of women’s toiletries on funerary monuments in Roman Italy,” (2008), 173. Earlier Greek views seem similar to these Roman theories on the softness of newborn bodies: massage is mentioned in the Hippocratic treatise On Regimen 1.19, and Plato uses the analogy of an artisan molding figures from wax to describe the development of a child just after pregnancy (Laws 7.789e); see Véronique Dasen, “Childbirth and infancy in Greek and Roman antiquity,” in A Companion to Families in the Greek and Roman Worlds, edited by Beryl Rawson (Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2010), 302. ↩︎

-

Clement of Alexandria, Paedagogos, 3.6.3–4. ↩︎

-

Plato, Timaeus, 91d. See Rebecca Flemming, “Wombs for the gods,” in Bodies of Evidence: Ancient Anatomical Votives, Past, Present and Future, edited by Jane Draycott and Emma-Jayne Graham (London: Routledge, 2017), 112–130; and Jessica Hughes, Votive Body Parts in Greek and Roman Religion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), esp. 103. ↩︎

-

See Jean-Baptiste Bonnard, “Male and female bodies according to ancient Greek physicians,” (2013), 12; Emmanuela Bianchi, “Receptable/Chora: figuring the errant feminine in Plato’s Timaeus,” Hypatia 1, no. 4 (Autumn 2006), 124–146. ↩︎

-

The Greek word for ‘receptacle,’ hupodoche, derives from the verb hupodechomai, which can mean ‘to host/entertain’ or, of a woman, ‘to conceive/become pregnant’; Emmanuela Bianchi, “Receptacle/Chora: figuring the errant feminine in Plato’s Timaeus,” (2006), 130. At Timaeus 50c-e, the Receptacle is described as an ekmageion, a word that denotes impress, model, or mold; Emmanuela Bianchi, “Receptacle/Chora: figuring the errant feminine in Plato’s Timaeus,” 127. ↩︎

-

On the seriality of Tanagras, and techniques of production and diffusion, see Arthur Muller, “The technique of tanagra coroplasts. From local craft to ‘global industry,’” in Jeammet, Tanagras (2010), 100–109. On the generative function of women’s bodies as prime emphasis of the Hippocratic treatises, see Rebecca Flemming, “Wombs for the gods,” 116. ↩︎

-

On which, see Ellen D. Reeder, “Women as containers.” ↩︎

-

Ellen D. Reeder, “Women as containers,” 195. ↩︎

-

Plato, Timaeus 91d. ↩︎

-

Menander frag. 720; cf. Sue Blundell, Women in Ancient Greece (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1995), 122. ↩︎

-

See Ellen D. Reeder, “Women as containers.” ↩︎

-

On the yoke as a metaphor for marriage, see Euripides, Medea, 240–245. Women were often characterized as wild animals that needed to be tamed, often through pregnancy; e.g. Plato, Timaeus, 91c. ↩︎

-

So, Hesiod declares, “For from her is the race of women and female kind” (Theogony 590). ↩︎

-

For discussion of the trope, see Kelly Olson, Dress and the Roman Woman. Self-presentation and Society, 304. In Ovid’s Remedia, 351–6, the pyxis with its repulsive contents is made analogous to the made-up woman; Amy Richlin, “Making up a woman: the face of Roman gender,” in Off with Her Head!: The Denial of Women’s Identity in Myth, Religion, and Culture, 190; Victoria Rimell, Ovid’s Lovers: Desire, Difference and the Poetic Imagination, 38. For the association of female make-up with poison, see Sarah Currie, “Poisonous women and unnatural history in Roman culture,” in Parchments of Gender: Deciphering the Bodies of Antiquity, edited by Maria Wyke (Oxford: Clarendon Press and Oxford University Press, 1998), 147–198; and with medicine, pointing to women’s inherent inferiority, see Rebecca Flemming, Medicine and the Making of Roman Women: Gender, Nature, and Authority from Celsus to Galen (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). ↩︎

-

Ars Amatoria 3.219–224. ↩︎

-

See Rita Berg, “Wearing wealth. Mundus muliebris and ornatus as status markers for women in Imperia Rome,” in Women, Wealth and Power in the Roman Empire, edited by Päivi Setälä (Rome: Acta Instituti Romani Finlandiae 25, 2002), 21–23. ↩︎

-

See Brigitte Bourgeois and Violaine Jeammet, "La polychromie des terres cuites grecques: Approche matérielle d’une culture picturale,"Revue Archéologique 69, no. 1 (2020), 3–28. ↩︎

-

Kelly Olson, “Cosmetics in Roman antiquity: substance, remedy, poison,” Classical World 102, no. 3, (Spring 2009), 294. ↩︎

-

Pliny NH 34.175–176; 28.139, 183, 34; 35.37; see Kelly Olson, “Cosmetics in Roman antiquity: substance, remedy, poison,” 295. ↩︎

-

E.g. Konstantina Tsatsouli and Elisavet Nikolaou, “The ancient Demetrias figurines: new insights on pigments and decoration techniques used on Hellenistic clay figurines,” STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research, Vol. 3, No. 2 (2017), 345. ↩︎

-

Pliny NH 35.37. ↩︎

-

E. Welcomme, P. Walter, E. Vanelslande, G. Tsoucaris, “Investigation of white pigments usedas make-up during the Greco-Roman period,” Applied Physics A: Materials Science and Processing, Vol. 83, No. 4 (June, 2006), 551-556. ↩︎

-

For sealings, Cicero, Pro Flacco, 37. As facial whitener: Martial 2.42, 8.33.17; Plautus, Truculentus, 294; Petronius 23. ↩︎

-

On the use of plaster casts in antiquity, see Elizabeth Bartman, Ancient Sculptural Copies in Miniature (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1992), 68. Leather patches might even be pasted onto the face to conceal imperfections; Kelly Olson, “Cosmetics in Roman antiquity: substance, remedy, poison,” 302. ↩︎

-

Kelly Olson, “Cosmetics in Roman antiquity: substance, remedy, poison,” 296. ↩︎

-

See Pat Hannah, “The cosmetic use of red ochre (miltos),” in Colour in the Ancient Mediterranean World, edited by Liza Cleland, Karen Stears, Glenys Davies (Oxford: Hedges, 2004), 100–105. ↩︎

-

Konstantina Tsatsouli and Elisavet Nikolaou, “The ancient Demetrias figurines: new insights on pigments and decoration techniques used on Hellenistic clay figurines,” 346–347; Brigitte Bourgeois and Violaine Jeammet, “La polychromie des terres cuites grecques: Approche matérielle d’une culture picturale,” 11. ↩︎

-

Soot and lamp black as kohl: Pliny NH 28.163; Juv. 2.93. Ashes (of goats’ meat) mixed with oil: Ovid, Ars amatoria 3.203; Pliny NH 28.166. See also Kelly Olson, “Cosmetics in Roman antiquity: substance, remedy, poison,” 298–299. ↩︎

-

Reynold A. Higgins “The polychrome decoration of Greek terracottas,” in Studies in Conservation 15: 272–277; L. A. Mau, and E. Farrell, “A pigment analysis of Greek Hellenistic Tanagra figurines,” in Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin 1, no. 3 (Spring 1993): 55–62. ↩︎

-

Brigitte Bourgeois and Violaine Jeammet, “La polychromie des terres cuites grecques: Approche matérielle d’une culture picturale,” 11. ↩︎

-

Ibid.,12. ↩︎

-

Ibid.,12. ↩︎

-

Violaine Jeammet, Céline Knecht, Sandrine Pagès-Camagna, “The polychrome decoration on Hellenistic terracottas: figurines from Tanagra and Myrina in the collection of the Musée du Louvre,” in Jeammet, Tanagras (2010), 246. ↩︎

-

Violaine Jeammet, “The Lady in Blue,” in Jeammet, Tanagras, 118. ↩︎

-

For an overview of gold textiles in the ancient Mediterranean, including material and literary evidence, see Margarita Gleba "Auratae vestae: gold textiles in the ancient Mediterranean, in Purpureae Vestes II, Vestidos, Textiles y Tintes: Estudios sober la produccion de bienes de consumo en la antiguidad, edited by C. Alfaro and L. Karali (Valencia, University of Valencia, 2008), 63–80. ↩︎

-

Brigitte Bourgeois and Violaine Jeammet, “La polychromie des terres cuites grecques: Approche matérielle d’une culture picturale,” 14–15. ↩︎

-

Pliny NH 32.85. ↩︎

-

Pliny NH 28.184. ↩︎

-

On Ovid’s Medicamina, see Victoria Rimell, Ovid’s Lovers: Desire, Difference and the Poetic Imagination, 2006. ↩︎

-

Ovid, Medicamina, 65; Pliny NH 24.106. ↩︎

-

Ovid, Medicamina, 83–85. ↩︎

-

Violaine Jeammet, Céline Knecht, and Sandrine Pagès-Camagna, “The polychrome decoration on Hellenistic terracottas: figurines from Tanagra and Myrina in the collection of the Musée du Louvre,” in Jeammet, Tanagras (2010), 246. ↩︎

-

See Adeline Grand-Clément, “Poikilia,” in A Companion to Ancient Aesthetics, edited by Pierre Destrée and Penelope Murray (Hobokon, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015). ↩︎

-

Ovid, Metamorphoses 10.243-297. ↩︎

-

On Ovid’s Pygmalion myth as model and metaphor for elegy’s transformation of the female love-object into an art-object, see Alison Sharrock, “Womanufacture.” ↩︎

-

See Dillon, “Case Study III: Hellenistic Tanagra Figurines,” 133, in the context of large-scale female portrait statues. ↩︎

-

On beauty norms as a mechanism of patriarchal social control, see generally Robin Lakoff and Raquel Scherr, Face Value: the Politics of Beauty, 2nd edition (Milton: Taylor & Francis Group, 2022); Joshua I. Miller “Beauty and democratic power,” Fashion Theory 6, no. 3 (2002): 277–297; for antiquity specifically, Richlin, “Making up a woman: the face of Roman gender,” (1995); Wyke, “Woman in the mirror: the rhetoric of adornment in the Roman world” (1994). ↩︎

-

Sue Blundell and Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz, “Women’s bodies, women’s pots: adornment scenes in Attic vase-painting,” 118. ↩︎

-

It is generally assumed that ancient Greek artisans in all media were male; certainly the majority of artists whose names survive in either the literary or epigraphic record are men, although female artists are also attested (see, e.g. Pliny NH 35.147–147). ↩︎

-

Kelly Olson, Dress and the Roman Woman. Self-presentation and Society, vol. 5, 110. For the importance of “pleasure” in feminist cultural theory and a new discourse that centers on the “liberatory possibilities of female viewing practices and pleasures”, see Suzanna D. Walters, Material Girls: Making Sense of Feminist Cultural Theory (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 89; Frost, “‘Doing looks’: women, appearance, and mental health,” in Women’s Bodies: Discipline and Transgression, edited by Jane Arthurs and Jean Grimshaw (London: Cassell, 1999), 134. ↩︎

-

Kelly Olson, Dress and the Roman Woman. Self-presentation and Society, 95; see also Eve D’Ambra, “Nudity and adornment in female portrait sculpture of the 2nd century AD,” 111, and Roman Women (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 32. On women as knowledgeable and adept cultural actors, see also Paula Black and Ursula Sharma, “Men are real, women are ‘made up’: beauty therapy and the construction of femininity,” The Sociological Review 49, iss. 1 (2001): 13; Kathy Davis “Remaking the she-devil: a critical look at feminist approaches to beauty,” Hypatia 6, no .2 (1991), 21–43. It is precisely because a woman could create space to assert herself socially through her agency that cosmetics and ornaments were censured in ancient discourses; Kelly Olson, Dress and the Roman Woman. Self-presentation and Society, 108. ↩︎

-

Leslie Shumka, “Designing women: the representation of women’s toiletries on funerary monuments in Roman Italy,” 173. See also Maria Wyke, “Woman in the mirror: the rhetoric of adornment in the Roman world,” 137. ↩︎

-

Leslie Shumka, “Designing women: the representation of women’s toiletries on funerary monuments in Roman Italy,” 183–186. ↩︎

-

Greek women controlled their dowries and could accumulate wealth, often in the form of textiles and jewelry; Sue Blundell and Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz, “Women’s bodies, women’s pots: adornment scenes in Attic vase-painting,” 127. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 120. Following Jean-Paul Sartre’s contention that the gaze renders whatever it sees as an object, Simone de Beauvoir argues that the very concept of ‘woman’ is a male concept: that woman is always the subject of the male gaze and hence is constructed by it; Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (English trans.) (New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2012). Repositioning women as the viewers of female bodies allows us to think about women’s self-creation through a self-regarding female gaze. ↩︎

-

On the power of replication across large-scale public portraits of women in the Roman period, see Jennifer Tremble, Women and Visual Replication in Roman Imperial Art and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011). ↩︎

-

Theogony, 590 ↩︎

-

See Richard Green, “The Caputi Hydria,” Journal of Hellenic Studies 81 (1961): 73–75. ↩︎

-

See Linda Merrill. On female potters in the Early Iron Age in Greece, see Sarah C. Murray, Irum Chorghay, and Jennifer MacPherson, “The Dipylon Mistress: social and economic complexity, the gendering of craft production, and early Greek ceramic material culture,” American Journal of Archaeology 124, no. 2 (April 2020), 215–244. On clay as medium associated with women-makers across cultures, see Moira Vincentelli, Women Potters: Transforming Traditions (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004). ↩︎

-

Sue Blundell and Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz, “Women’s bodies, women’s pots: adornment scenes in Attic vase-painting,” 139. ↩︎

-

Sue Blundell, “Clutching at clothes,” (2002). ↩︎

-

Kelly Olson, “Cosmetics in Roman antiquity: substance, remedy, poison,” 305. The most common Roman word for make-up, medicamentum, can also be translated as “remedy” or “poison.” ↩︎

-

Pliny NH 35.33–34; 28.104; cf. Krzysztof Spalek and Izabela Spielrogel, “The use of medicinal clay from Silesia ‘Terra sigillata Silesiaca’, Central Europe - A New Chance for Natural Medicine?,” Biomedical Journal of Scientific and Technical Research (2019). ↩︎

-

On signets’ function as emblems of personal identity, see Ruth Allen, “A cultural history of engraved Roman gemstones - their material, iconography, and function.” ↩︎

-

Amy Richlin, “Making up a woman: the face of Roman gender,” in Off with Her Head!: The Denial of Women's Identity in Myth, Religion, and Culture, edited by Howard Eilberg-Schwartz and Wendy Doniger (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 186. ↩︎

-

See Beth Cohen, “Tanagra Mania and Art: Fashioning Modernity via Ancient Greek Female Imagery.” ↩︎

-

Violaine Jeammet, “Veiled dancers,” in Jeammet, Tanagras (2010), 89–91. ↩︎

-

Onomasticon, 4.100; cf. Ismene Lada-Richards, Silent Eloquence: Lucian and Pantomime Dance. (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013), 179. ↩︎

-

Pre-empting, perhaps, the inspiration drawn by feminist dress reformers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, who saw in the loose folds of the Tanagras’ drapery opportunities for emancipation from the corset and from male control of female bodies; see Eugenia Paulicelli, Rosa Genoni. Fashion is a serious business: the Milan World Fair of 1906 and the Great War (Milan: Deleyva editore, 2015). ↩︎