Professional models are a purely modern invention. To the Greeks, for instance, they were quite unknown.

—Oscar Wilde, “London Models,” 1899

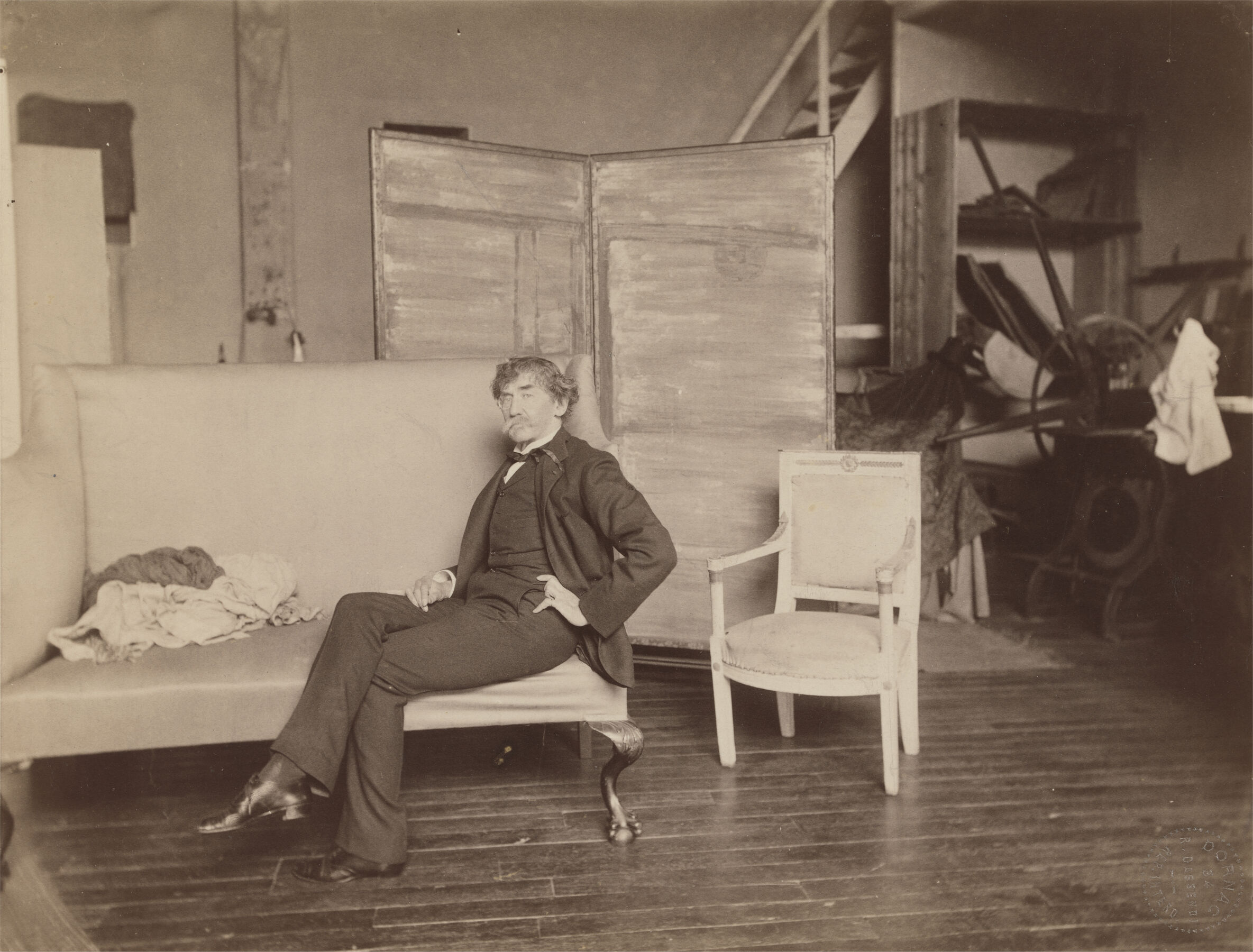

The models who arrived at Whistler’s studio around 1890 were invited to remove their hats, coats, corsets, and boots, and leave their cares and inhibitions at the door. Once inside, they might don some diaphanous drapery, perhaps with a kerchief to hold back their hair, or they might wear nothing at all. The furnishings were sparse in the cavernous space, but there was a stove for warmth, a sofa for naps, and other small comforts to help the models feel at home. We know from one eyewitness that Whistler did not expect them to strike a pose; they were free to wander about the studio—lounging, dancing, reading—until some unconscious movement or attitude caught the artist’s eye and “seemed to him a picture.”1 The resulting “figures” (as images of nude and draped models are known) were often rendered in the form of lithographs, prints that capture and multiply the lightest touch of the artist’s hand.

Although Whistler referred to these easygoing studio pictures simply as “draped & nude figures,”2 scholars and collectors often call them “Tanagras,” a title of convenience we are happy to adopt.3 The term is properly applied to the ancient terracotta figurines unearthed during the final decades of the nineteenth century around the ancient city of Tanagra, in the Boeotian region of Greece, but it evokes the delicate grace that distinguishes this category of Whistler’s imagery. His so-called Tanagras do not depict Tanagra figurines, in which the body is typically enveloped in drapery, but they represent a similarly informal interpretation of a statelier classical style.

If Whistler never explicitly related his assertively modern works to the ancient terracottas, he tacitly acknowledged the aesthetic affinities that were obvious to his contemporaries. Perhaps the first to make the connection was Oscar Wilde, who in 1882 associated Whistler’s art with Tanagra figurines, each “as delicate in perfect workmanship and as simple in natural motive” as the other.4 Elizabeth Robins Pennell, in an 1897 article for Scribner’s Magazine written in close consultation with the artist, observed that “these studies have been likened, more than once, to the work of Tanagra; and justly, for theirs is the same flawless daintiness, the same purity of pose, the same harmony of line, the same grace of contour.”5

James Abbott (later McNeill) Whistler was born in Massachusetts, but his life as an artist began in Paris. Arriving at age twenty-one, he was already fluent in French from a childhood spent in imperial Saint Petersburg, and he was conversant with the culture of the Latin Quarter from repeated readings of Henri Murger’s Scenes of Bohemian Life. Nominally an art student, Whistler never submitted to the traditional academic training that would have compelled him to draw from plaster casts of classical sculptures before proceeding, at length, to drawing from life (the nude model), and it was not until years later, when he was already established as an artist in London, that he came to appreciate the cost of his neglect. In 1867, a well-respected art critic condemned Whistler’s figures as poorly drawn, “an impertinence of which the artist ought to be as much ashamed as we hope he would be if found in a drawing-room with a dirty face.”6 He was indeed chagrined. “What a frightful education I gave myself,” Whistler lamented to Henri Fantin-Latour, his best friend in Paris, “or rather what a terrible lack of education I feel I have had!” Under the “odious” influence of Gustave Courbet, he had allowed the attractions of Realism to lure him from the studio. Now, at age thirty-three, he would have to start over from the very beginning. “I’m sure I will make up for the time I’ve wasted—but what difficulties,” he wrote. “I spend the whole day drawing from models!!”7

With his new friend Albert Joseph Moore (1841–1893), an English artist equally lacking in formal training, Whistler practiced making “academy studies” from the nude figure. Until then, his artworks had depicted scenes from modern life, while Moore’s had tended toward antiquity, visions of beauty remote from the contemporary world. With his meticulous working methods and high aesthetic ideals, Moore was the antithesis of—and for Whistler, the antidote to—Realism and Courbet. Whistler carried out his remedial project from a rented studio overlooking the British Museum, which housed the architectural sculpture from the Parthenon. For Whistler and his contemporaries, the Elgin Marbles represented the summit of artistic achievement: “the best and highest—never likely, or even possible, to be excelled in any future age of the world.”8 Thus it was that Whistler attempted to formulate an original approach to ideal, or abstract, beauty in the shadow of that epitome of perfection.

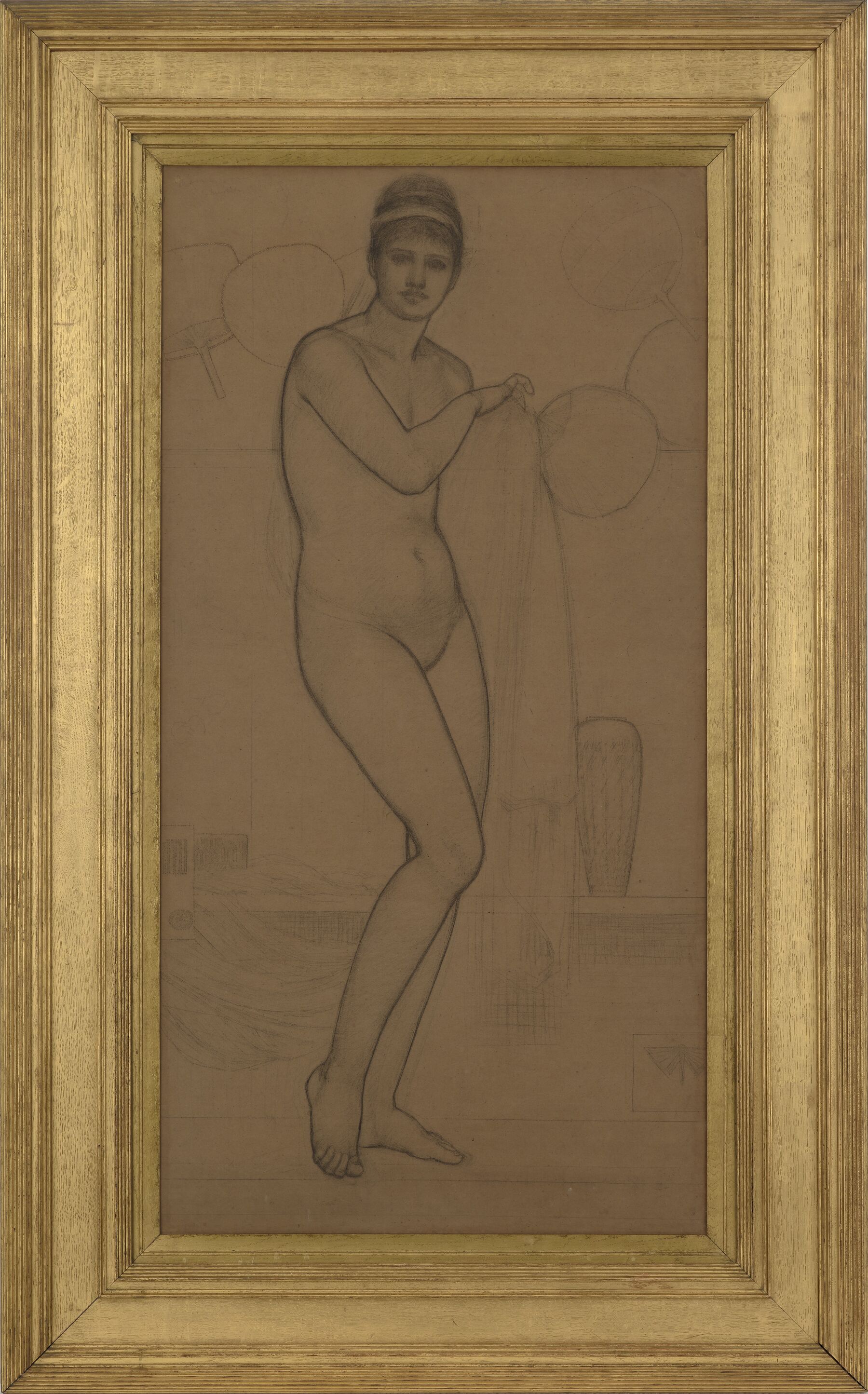

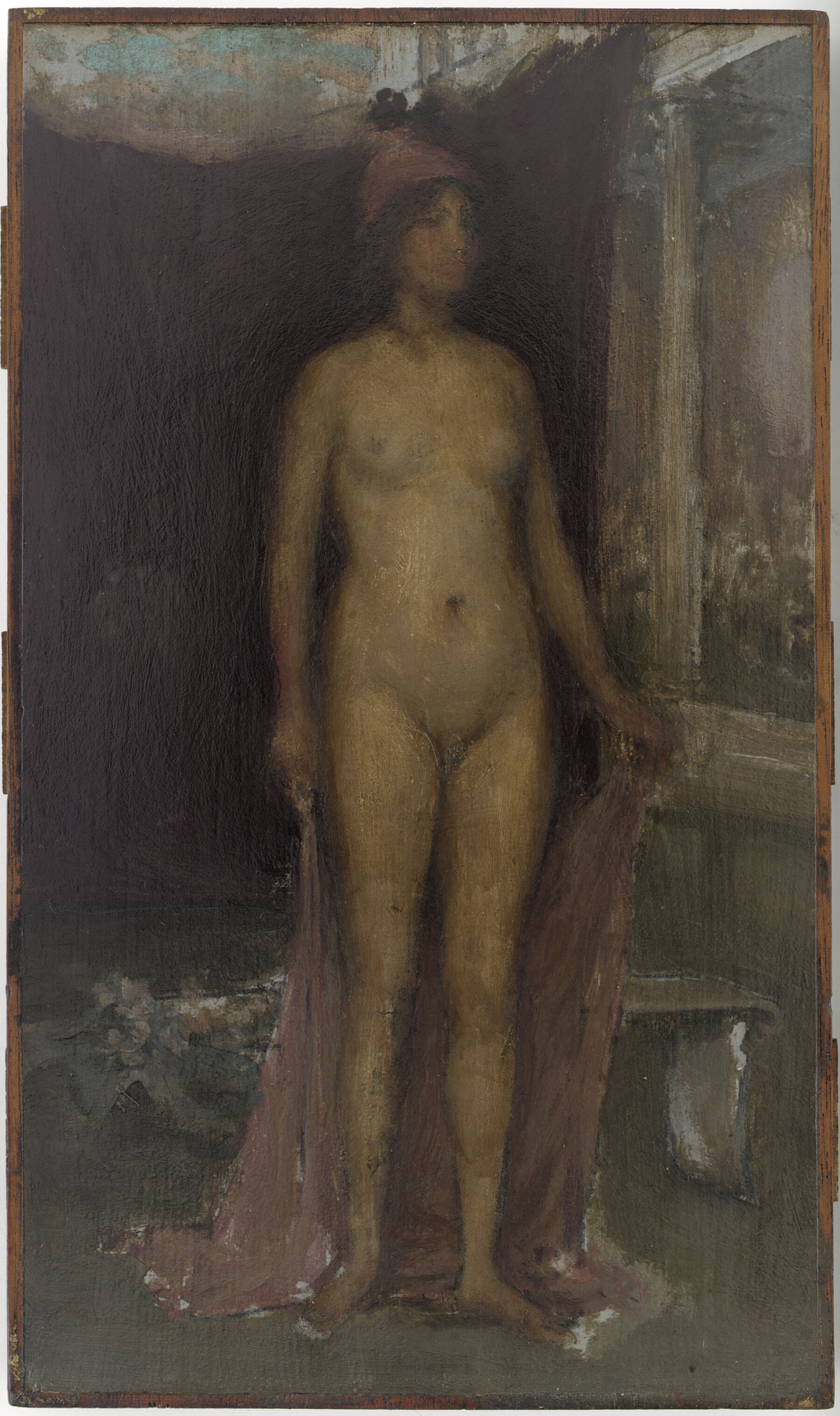

In keeping with the seriousness of his enterprise, Whistler’s “academic” drawings from the latter 1860s appear studiously remote and disaffected. He was undoubtedly intimidated by his project, as a passage in Pennell’s Scribner’s article implies: “By his drawing of the nude, the measure of an artist’s capacity—or incapacity—may be judged. By it he stands convicted of perfection, or of failure as it may be and too often is.”9 Standing Nude (fig. 3.1), an overdetermined effort to portray the calm repose of classical art, betrays Whistler’s own discomfort with both the female nude and the academic exercise. The unnamed figure (inevitably called “Venus”) is vaguely reminiscent of antique statuary—like the Medici Venus, her right arm shields her breasts, and like the Venus de Milo, her left arm is absent altogether—which suggests, as Margaret MacDonald has observed, “that the themes and variations of classical art were more or less absorbed in Whistler’s consciousness.”10

Figure 3.1: James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903), Standing Nude (Venus) (M.357), 1869. Black crayon with touches of white chalk on brown paper, 47 x 24 3/16 in. (119.4 x 61.4 cm). Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution; Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1904.66. Image CC0 1.0.

Although shaded like a finished drawing, Whistler’s Standing Nude was intended as a cartoon, or full-size pattern for a painting, in which the figure would be clothed, or as the artist informed a potential patron in 1869, “clad in thin transparent drapery.”11 A small oil sketch made to determine the color scheme (cat no. 14), a custom adopted from Moore, provides a key to Whistler’s vision for the final work. A violet scarf tied around the figure’s head swirls behind her to connect with the white-dotted sash pulled across her body and gathered lightly with a swathe of pink drapery in one hand; the other holds a circular Japanese fan like the ones pinned arbitrarily to the wall behind her. That unexpected accessory emblematizes the wave of inspiration flowing from Japan, which Moore and Whistler both insinuated into their classicizing art. Standing beside the figure is a slender blue and white vase evocative of Chinese porcelain; it holds vivid purple irises that pick up the shade of the sash like the thread of an embroidery, as Whistler explained his technique, “the whole forming in this way an harmonious pattern.”12

Whistler’s little oil, known for decades as Tanagra, was long believed by many scholars (including myself) to be an homage to the ancient terracottas.13 We were led astray by the title, posthumously assigned to the sketch because of its presumed connection with a pastel drawing once exhibited by that name.14 But even without its Greek misnomer, Whistler’s elegantly draped figure, fan in hand, resembles a Tanagra figurine, and the small scale, delicate facture, and muted colors of the work lend further support to the association. It is unlikely, however, that Whistler or anyone else in his circle had ever laid eyes on an actual Tanagra as early as 1869, when the oil sketch was made.15 As the Louvre historian Néguine Mathieux has remarked, certain artists were painting “Tanagras,” or “young draped women depicted with an idealized grace and in pastel colours,” even before the actual Tanagra figurines were unearthed in Greece.16

That Whistler fell under the spell of the terracotta figurines has never been in doubt. They offered a welcome alternative to the implacable perfection of classical Greek art, adhering to a more attainable standard of beauty and personifying a more modern sensibility. “The calm repose of antique art is here replaced by vivacity and movement,” the antiquarian Frederic Vors observed in 1879: “They are the embodiment of momentary action and transitory motion.”17 Whistler’s silence on the subject makes it impossible to know exactly when, or how, he first encountered the Tanagras, though hints of influence begin turning up in his works around 1873, just as the figurines were making their way into museum collections and private hands. Katharine Lochnan has identified an etching of a draped standing figure (fig. 3.2) as the first of the “Tanagras,” detecting in the hairstyle a hint of the distinctive “melon” coiffure and noting in the drapery the arrangement of chiton and mantle that make up the Tanagra costume.18

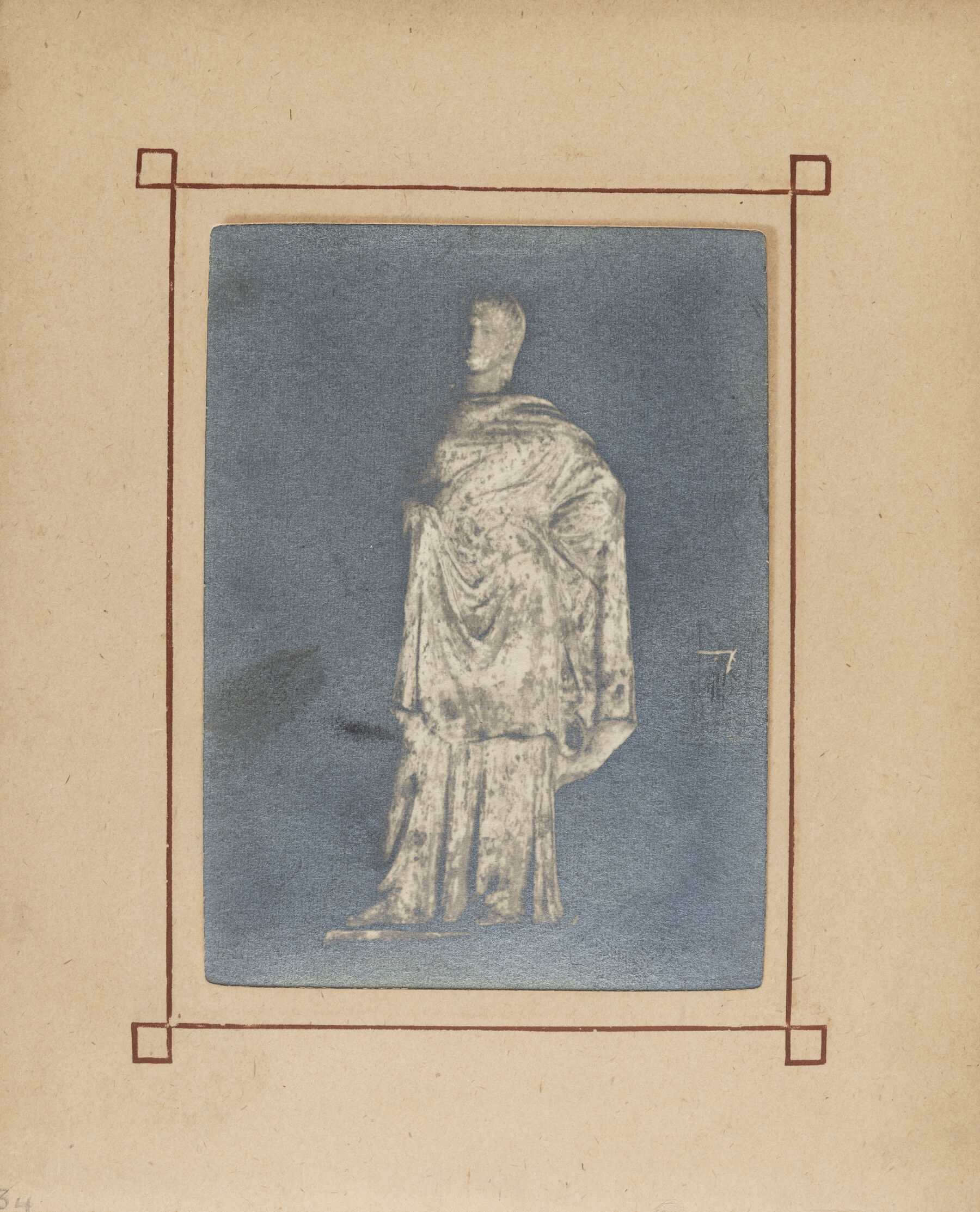

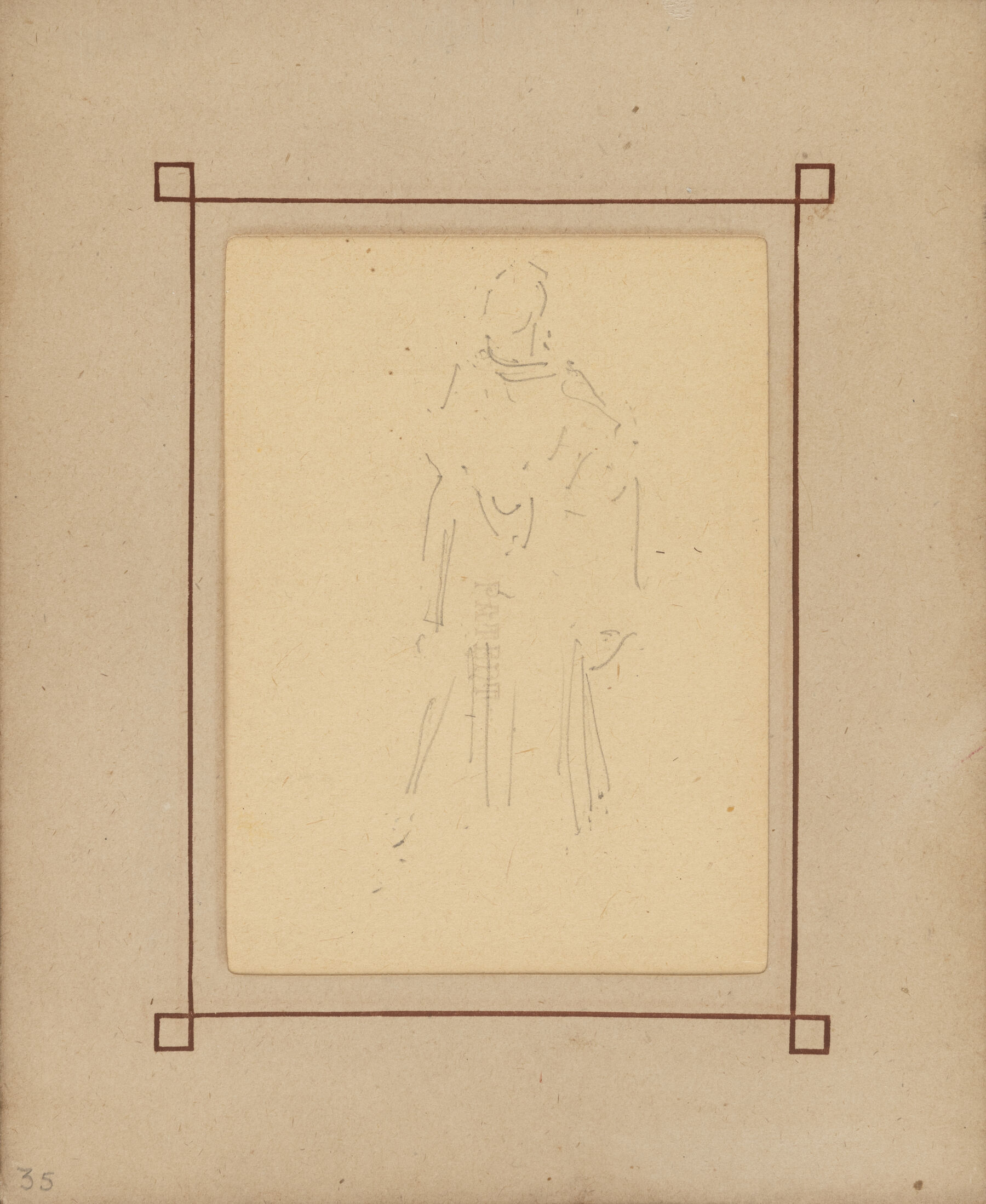

Beyond such visual clues, which might also point to a continuing engagement with the classical, only circumstantial evidence supports the speculation that as early as the 1870s, Tanagras inspired Whistler’s creativity. In fact, the only irrefutable physical evidence that the artist ever acknowledged the aesthetic possibilities of the ancient terracottas is a faint pencil sketch (fig. 3.3) of a photograph of a single statuette (fig. 3.4), which could not have been made before the mid 1890s. The sketch is preserved in an album that was probably lent to the artist by his friend Alexander A. Ionides (1840–1898), who possessed a celebrated collection of Tanagras and thus became, in the words of John Sandberg, the artist’s “direct path to classical antiquity.”19

Figure 3.2: James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903), The Model Resting (Draped Model) (G.109), 1873–74. Drypoint, printed in black ink on ivory laid paper, ninth state of eleven, 8 1/8 x 5 1/8 in. (20.7 x 13 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art., New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1917; 17.3.67. Image: Public domain courtesy of the Met’s Open Access Policy.

Figure 3.3: Photograph of a Tanagra statuette of a standing female figure, probably 1894. In from the Ionides Album, ca. 1894. Carbonprint on paper in photograph album. Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow; Bequeathed by Rosalind B. Philip (1958), GLAHA:4639. Image © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow.

Figure 3.4: James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903), Sketch after a Greek terracotta figure (M.1419), probably 1895. Pencil on cream card, 6 1/8 x 5 in. (15.5 x 12.7 cm). Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow; Bequeathed by Rosalind B. Philip (1958), GLAHA:46205. Image © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow.

A Connoisseur’s Treasures

Aleco, as Alexander Alexander Ionides was known to his friends, met Whistler in Paris in 1855. He was there to improve his French, although at sixteen he already spoke the language like a native, according to George du Maurier, whose 1894 novel Trilby is based on his own reminiscences of his art-student days. “The Greek,” as du Maurier calls Aleco, was popular with the artists “for his bonhomie, his niceness, his warm geniality,” and also because “he was the capitalist of this select circle (and nobly lavish of his capital).” When Whistler and his Parisian colleagues “transferred their bohemia to London” around 1860, they were warmly welcomed to the Ionides’s gracious family home in Tulse Hill, on the outskirts of town.20

The patriarch was Alexander Constantine Ionides (1810–1890), who had fled Constantinople in 1827, eventually settling in London with his wife, Euterpe Sgouta. Over the years, he shifted the family business from the import trade to merchant banking, and from 1854 to 1866 acted as consul general for Greece. Within months of Aleco’s birth in 1840, his father commissioned a family portrait, in which the chubby-cheeked baby poses with his elder brothers Constantine (1833–1900) and Luke (1837–1924), both in traditional Greek costume. The portraitist, George Frederic Watts, became a close family friend, and it was he who called the elder Ionides’s attention to the first work Whistler exhibited at the Royal Academy, At the Piano. Consequently, Ionides commissioned Whistler to paint a Thames scene and a portrait of his son Luke,21 and went on to encourage his own children and others in his extended family to support young artists trying to find a foothold in the competitive London art world.22

Euterpe Ionides sold her diamonds in 1864, or so the story goes, to buy No. 1 Holland Park, a newly constructed mansion in a fashionable Kensington neighborhood. Whistler was a frequent visitor to the house until 1867, when he was involved in a dispute with his own brother-in-law, and Aleco was the only member of his family to take the artist’s side.23 Some years later, when Whistler’s brother William married Aleco’s cousin Helen (known as Nellie), the friendship was sealed with a family bond. By then, Aleco Ionides had become “a swell,” as Whistler remarked in 1873, by which he meant a distinguished person with a prospering career in the City. Aleco was also beginning to manage the household in Holland Park while his parents gradually retired to Windycroft, their country home near Hastings.24

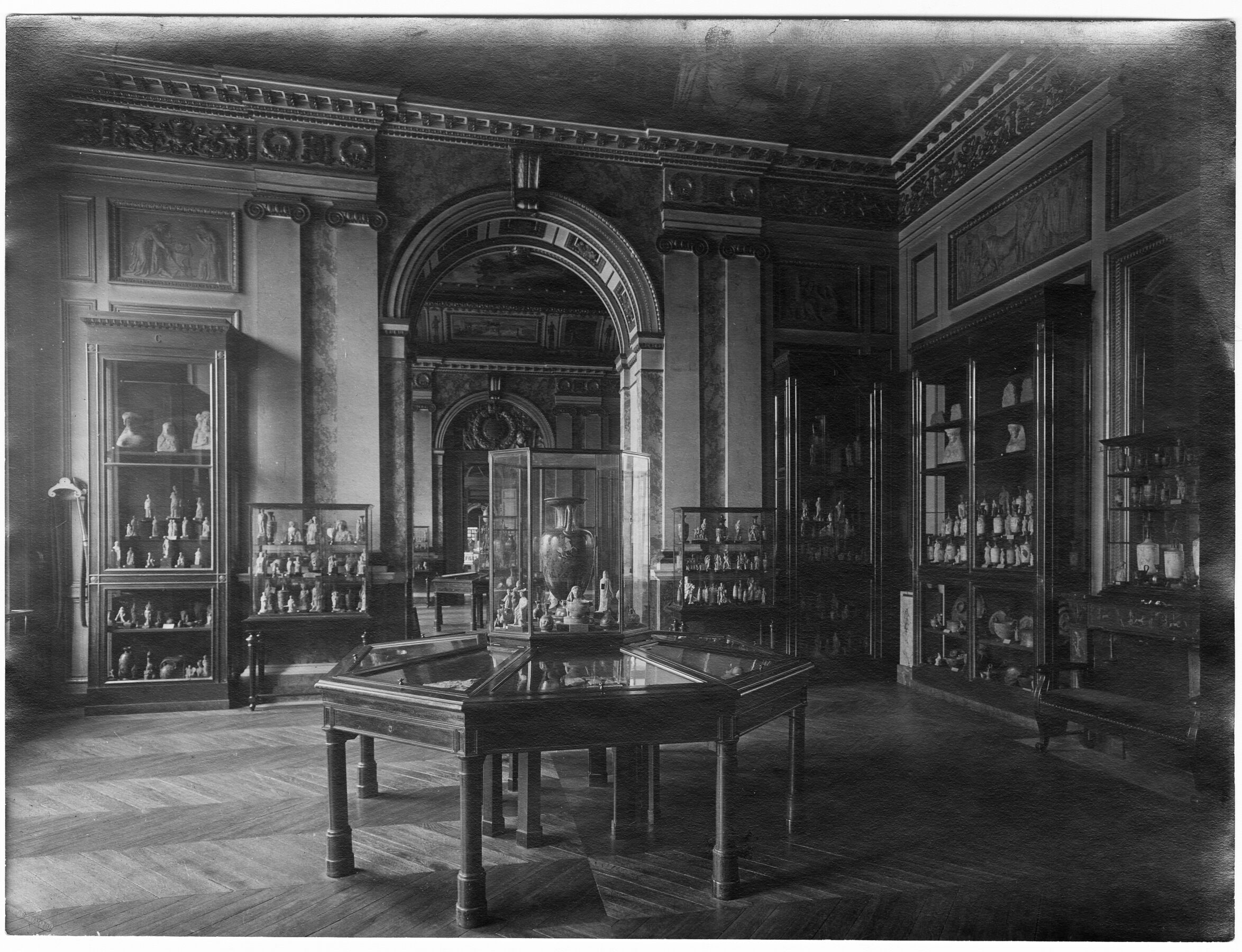

In 1875, Aleco Ionides married Isabella Sechiari, another member of the Anglo-Greek community, though born in Marseille. On their honeymoon in Paris, they visited the Louvre expressly to see the Tanagra figurines. The museum had made its initial acquisitions in 1872, assisted by the young archaeologist Olivier Rayet, who had been in Athens when the figurines first appeared on the market. By 1874, over sixty “specimens” went on display in mahogany cases lining the walls of the Charles X Gallery (fig. 3.5).25 Aleco and Isabella may have been motivated to see the collection for themselves by an illustrated article published in the April issue of the Gazette des Beaux-Arts (cat. no. 49). Written by Rayet himself, it provided an “historic and descriptive account of the curious statuettes and other small works of Greek art discovered at Tanagra in Boeotia.”26

Figure 3.5: Charles X Gallery, former room L, Louvre Museum, May 1922. Photographic print, °TP_004458. Image © Département des Antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines, musée du Louvre.

Although the Louvre collection was considerably larger, the Ionides family’s collection was “as perfect,” the newlyweds decided.27 From that observation we may surmise that it had effectively taken shape by 1875. Marcus B. Huish, writing in 1898, begins his chronicle of the Ionides collection “some five-and-twenty years ago,” when “the spade awoke from their sleep of centuries the assemblage of elegant and coquettish figurines which had only to be seen to be appreciated.” Aleco Ionides was “on the spot,” according to Huish—a statement that cannot be verified and may have been contrived to confirm the collection’s authenticity.28 Nevertheless, Aleco’s father probably retained diplomatic ties from his term as consul general, and the family’s connections with the Archaeological Society of Athens (though it did not begin to excavate the site until 1874) may also have facilitated the acquisition and export of fresh antiquities from Tanagra.29

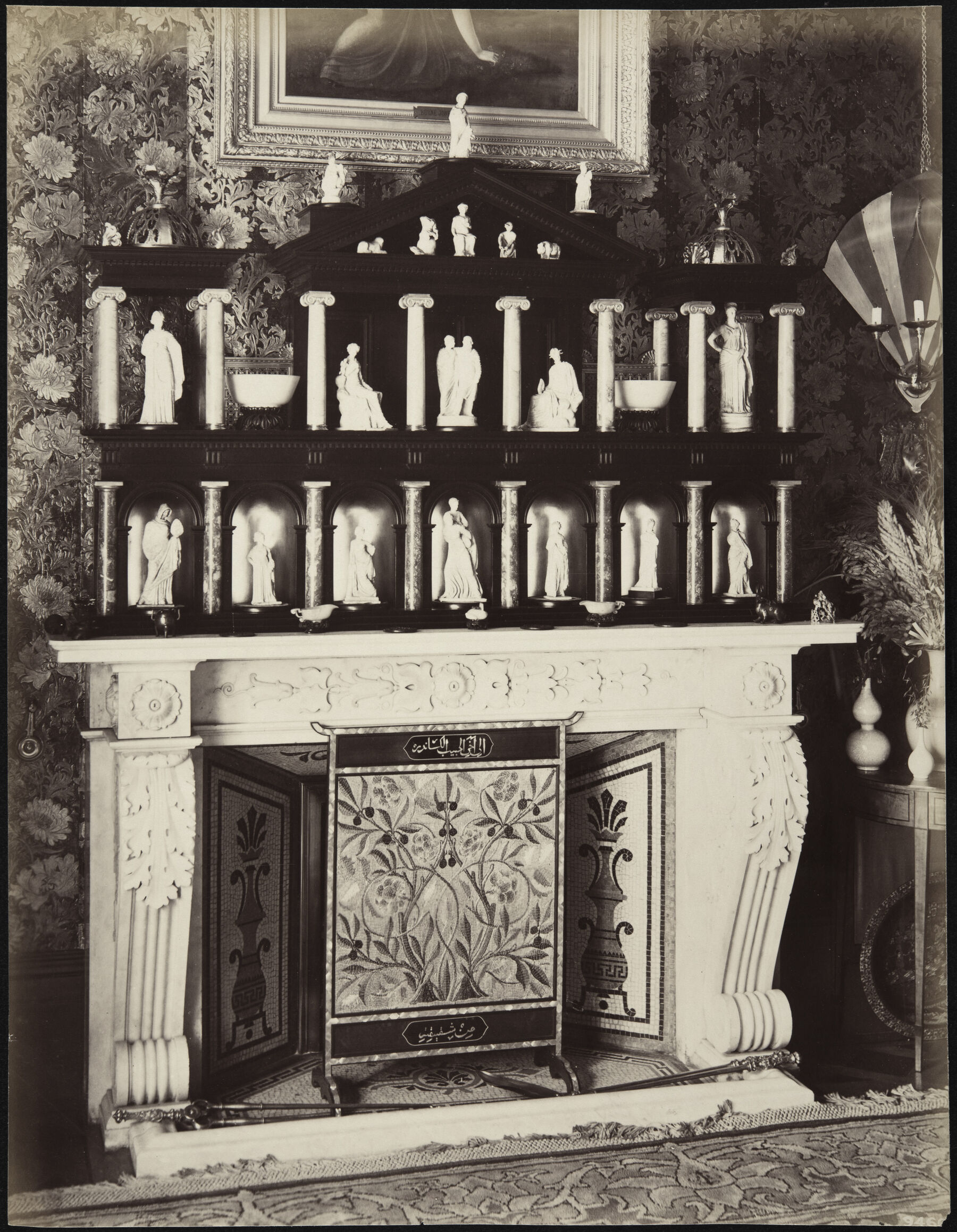

Over the next few years, as Aleco’s social standing rose—he himself was appointed Greek consul general in 1883—his holdings of Tanagra figurines continued to expand, and in January 1885 the collection earned official sanction with an exhibition at the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria & Albert).30 Once back at Holland Park, the figurines were installed in a drawing room recently remodeled into an “antiquities room,” which gave them pride of place. The artist Walter Crane (1845–1915) had been commissioned to create a showcase for their display (fig. 3.6), a two-tiered, pedimented structure which surmounted the fireplace like an overmantel, that typically Victorian construction designed to draw attention to the hearth of the home by surrounding it with the owner’s possessions. Crane described his construction as “a sort of temple-like cabinet” made of ebony, with columns of red and yellow marble, “midway in tone between the extremes of light terra-cotta and dark limestone.” On the lower level, Doric columns defined seven arched niches with gilded recesses for individual figurines; the upper tier, in the correct Ionic order, was divided into three sections to give special prominence to prized terracottas.31

Figure 3.6: The fireplace in the drawing room at No. 1 Holland Park, London, with the Ionides Collection of Tanagra figurines, 1889. Photograph (albumen print) by Bedford Lemere & Co., BL09466. Image © Historic England Archive.

The shrine was designed to hold the collection as it stood in 1889, when it was photographed by Bedford Lemere, together with other rooms and works of art at Holland Park. Those photographs illustrate an account of the Ionides house written by the designer Lewis F. Day and published in the Art Journal in 1893 (cat. no. 53). According to Day, who would have heard it from Aleco, those original figurines were “among the first found at Tanagra, before ever forgeries were thought of.” By then, the trade in forgeries was openly acknowledged: the first had been made around 1876, and ten years later it was estimated that three times as many fake as genuine terracottas were sold each year.32 Nevertheless, Aleco persevered, trusting his eye and intuition despite persistent reports of fraud in the antiquities market. Indeed, Day mentions two recently acquired Tanagra statuettes that were too new and probably too ornate to find a place in the overmantel. Those mythological subjects, sure to appeal to late-Victorian taste, were almost certainly forgeries (fig. 3.7).33

Figure 3.7: Photograph of a Tanagra Statuette of the Rape of Europa from the Ionides Album, ca. 1894. Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow, Bequeathed by Rosalind B. Philip (1958), GLAHA:46220. Image © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow.

In the dining room, lavishly decorated by Crane and William Morris, Whistler’s self-portrait, Arrangement in Grey, hung prominently beside the fireplace. Aleco had inherited the painting upon his father’s death in November 1890,34 just after acquiring a Whistler of his own, Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Valparaiso, a more radical example of the artist’s increasingly abstract style. Because the walls at Holland Park were by then replete with pictures, the Nocturne would hang at Homewood, the family’s country house in Surrey, where the light, in any case, was “so much better for it,” Aleco assured his friend.35 At least initially, Aleco proved to be among the rare few who lived up to the artist’s expectations of those who owned his works—or cared for them on his behalf, as Whistler understood the situation. Aleco generously allowed his new acquisition to be exhibited in the Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées in 1890 and again in London in 1892, at the Whistler retrospective held at the Goupil Gallery. Indeed, on the latter occasion, Aleco offered to lend every Whistler painting in his possession.36

The reason for his magnanimity became apparent when Aleco Ionides allowed Nocturne in Blue and Gold to be sold from the walls of the Goupil exhibition. To Whistler’s dismay, Aleco had become one of many old friends and acquaintances who capitalized on the phenomenal rise in the artist’s reputation. “How shockingly they have all behaved about my pictures,” Whistler complained to his sister-in-law about her Greek relations, Aleco in particular. A few months later he informed her bitterly that Aleco had received £200 for “another little sea piece of mine,” purchased for around £20 soon after it was painted in Trouville in 1865, or so the artist recollected.37 As it happened, the sale of the Whistlers portended a precipitous fall in the fortunes of Aleco Ionides. In March 1894, he approached David Croal Thomson, Whistler’s dealer at Goupil, about selling Brown and Silver: Old Battersea Bridge, the painting his father had commissioned and he had inherited when his mother died in 1892. “I fear he is very hard pressed at the present,” Thomson wrote to Whistler, “for he spoke of getting rid of his whole house & its contents.”38

Whistler, affronted that Aleco had not told him personally, was nonetheless aware of his old friend’s straitened circumstances and agreed to help him sell his collection of Tanagra figurines.39 Aleco probably enlisted Whistler’s assistance because the artist owed him a favor, after his generosity as a lender. Moreover, Whistler’s rising reputation in the international art world meant that he would have the connections necessary to effect a sale of such significance. The artist’s first (perhaps only) thought was of Professor Emil Heilbut, a scholar, collector, critic, and occasional art agent, who had been the first person in Germany to acquire French Impressionist paintings; because Heilbut was also one of Whistler’s greatest admirers, he could be counted on to cooperate. In April 1894, Whistler offered to send photographs of the Ionides Tanagras as soon as they were ready, and in July, Heilbut paid a visit in person to Holland Park, later writing to Whistler that he had found the collection “admirable” and would do what he could to help sell it.40

A German buyer was not forthcoming, however, probably because of the well-founded fear of forgeries. Thomson tried, to no avail, to interest the American industrialist Alfred Atmore Pope in the Tanagras, arranging for him to visit Holland Park, which Thomson had “represented,” Pope wrote afterward to Whistler, “as the most artistically decorated house in London.”41 While the collection languished, the strain on Aleco began to tell. In a letter Whistler wrote that June to his brother William, he mentioned Aleco’s distracted state: “I never know whether he is not thinking of something else.”42 Finally in 1895, the “lovely company of Tanagra figures,” together with the other remaining works of art at No. 1 Holland Park, were packed up and sent to Bond Street for exhibition, and implicitly for sale, in a show discreetly titled A Connoisseur’s Treasures. Even though the connoisseur was named only as “a distinguished amateur,” his identity would have been an open secret in the London art world.43

Whistler was living in Paris at the time, but he heard from Thomson that the Ionides show was attracting many visitors, although “very little business is being done.”44 The Tanagras did not attract the attention Aleco expected; he had informed Marcus Huish “that of all his beautiful things none have so quickly appealed to all, no matter how varied their tastes, as these groups and figures.”45 One work did sell, however—Arrangement in Grey, for the considerable sum of £700, “a large price for a head,” Whistler reflected, “even though it be my own.”46 Yet the artist was again irrationally incensed that Ionides had realized so much profit from one of his works. “Out of softness of heart,” he wrote to Aleco, in what would be his last letter to his old friend,

I let you off a while ago—and tried to help you in the sale of your Tanagras.

But it is intolerable that all of you in England should under my nose, in this sly way—turn these pictures of mine over & over again, & without a word to me pocket sums that properly you should offer to me on your bended knees saying behold the price we are at last able to obtain for these valuable works we have had the privilege of living with all these years for eighteen pence!

Whistler seems to have regarded the album of Tanagra photographs, which had remained in Thomson’s hands for the duration of the exhibition, as now belonging to him, perhaps in compensation for what he regarded as his friend’s ill-gotten gains.47 He kept it for the rest of his life, and at some point between 1895 and his death in 1903 sketched one of the figurines on a blank album page (see fig. 3.3).

The Tanagra terracottas remained unsold. Ionides had provided for this eventuality in his will of 1889, stipulating that the collection remain within the house at Holland Park as long as it was occupied but then return to Greece, to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.48 The rest of the story is shrouded in mystery. A childhood friend of Aleco’s who paid a call in 1897 found him as “kind and affectionate as ever,” though “down on his luck and ill.”49 At the end of that year, the Studio published a richly illustrated account of the palace of art in Holland Park, “An Epoch-Making House” by Gleeson White, and six months later Marcus Huish’s article devoted to the Tanagras appeared in the same publication.50 Shortly after that, at the end of July 1898, Alexander A. Ionides died at home, age 58, in circumstances that have never been disclosed. No obituary appeared in the papers; indeed, for all the family’s prominence in London, there seems to have been no official notice of his passing.

His fortune had dwindled, but Aleco Ionides did not die destitute. The total estate was valued at around £19,000—the equivalent today of some $3.25 million—with small bequests to charitable institutions in Athens, but most of the fortune was left to his family.51 Isabella Ionides and the children deserted Holland Park for their country home but kept the London house until 1908, when it was sold to the trustees for the sixth Earl of Ilchester. By then, the terracottas were long gone, though they had not returned to Greece in accordance with Aleco’s wishes. “The Well-known Collection of Objects of Art formed by the late Alexander A. Ionides Esq. of 1 Holland Park W., including an important series of Antiquities from Bœotia, Tanagra, Greece, etc.,” had been dispersed at a Christie’s auction on March 14, 1902, with the terracottas selling as a single lot for £5,250.52 Apart from a few minor examples held by the Harvard Art Museums (cat. no. 11), the Ionides collection has since disappeared.53

The Models of Chelsea

In February 1885, just as popular appreciation for Tanagra figurines was coming into full flower, Whistler delivered a lecture on art titled the “Ten O’Clock” after the late-night hour of its presentation. In that formal declaration of the aestheticist creed, Whistler defines the artist as one “who delights in the dainty, the sharp, bright gaiety of beauty.” “Dainty” is not a word we often use today, except in reference to something ridiculously delicate and out-of-date, but that unassuming little adjective evoked, for Whistler, the highest form of aesthetic beauty. Indeed, he envisioned art itself (Art for Art’s Sake) as “a goddess of dainty thought—reticent of habit, abjuring all obtrusiveness, purposing in no way to better others.”54 Rather like a Tanagra figurine, Whistler’s muse is classical in her allegorical aspect but naturalistic, even human, in her capricious affections—which the artist had learned, to his grief, never to take for granted.

We might expect to find Tanagras somewhere in the “Ten O’Clock,” if only listed among the artworks sanctioned by the goddess, but they are never mentioned by name. This may have been because they were so much in fashion. Whistler’s discourse even criticizes the vogue for classical antiquity, a flicker of hypocrisy seized upon by his sometime friend and neighbor Oscar Wilde: “Has not Tite-street been thrilled with the tidings that the models of Chelsea were posing to the master, in peplums, for pastels?”55 Whistler was in fact making “striking drawings of very graceful figures” around that time, according to one visitor to his Tite Street studio, though his models never posed in “peplums.” They posed in the nude, or draped in sheer fabrics that revealed their natural form. As one critic noted dryly, their “excessively slight drapery is the result of some half dozen strokes of the crayon.”56

Those works in pastel built upon—indeed, superseded—the serious studies from the life model that Whistler had made in the 1860s and '70s to atone for his misspent youth. In at least one case, Note in Violet and Green (fig. 3.8), infrared photography reveals that Whistler simply added color to an older drawing.57 And we can see from the reversal of the image that the pastel known as The Greek Slave Girl (Variations in Violet and Rose) was made from a tracing of Whistler’s early lithograph Study (see fig. 3.12).58 As revisions of monochrome figures, these colorful pastels may have been inspired by the growing publicity surrounding Tanagra figurines, which often called attention to “the finely powdered remains of a suit of paint.”59 The vestiges of color clinging to the clay surfaces accounted for much of their popular appeal; in an age obsessed with the myth of Pygmalion, even the hint of color on an antique statue made it seem to come alive, or at least appear more accessible than the polished white marbles in the British Museum.

Figure 3.8: James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903), Note in Violet and Green (M.1074), ca. 1872/1885. Crayon and pastel on brown paper, 27.8 x 16.7 cm (10 15/16 x 6 9/16 in.). National Museum of Asian Art. Smithsonian Institution, Freer Collection, Washington, D.C., Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1905.128a-b. Image: Public domain via CC0.

Upon seeing a selection of Whistler’s pastels in 1885, the neoclassical sculptor William Wetmore Story thrilled the artist with his exclamation, “Whistler, they are as charming and complete as a Tanagra statue!”60 The analogy may have been prompted by a work such as A Study in Red (fig. 3.9), whose French title, Danseuse athénienne (although not Whistler’s), provides a clue to a possible source of inspiration: the famous terracotta figurine of a veiled dancer discovered in 1846 near the Athenian Acropolis and known as Danseuse Titeux, or the Titeux Dancer (cat. no. 1). That terracotta prototype, a pre-Tanagra figurine, had become widely known to artists and antiquarians throughout Europe,61 and Whistler may have intended to recall the figure with his own dancing girl, drawn in pastels on the rough brown paper that approximated the texture and tonality of fired clay.

Figure 3.9: James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903), A Study in Red (Danseuse athénienne) (M.1072), 1890. Crayon and pastel on brown paper, 27.7 x 18.3 cm (10 7/8 x 7 3/16 in.). National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Freer Collection, Washington, D.C., Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1909.123. Image courtesy of the National Museum of Asian Art.

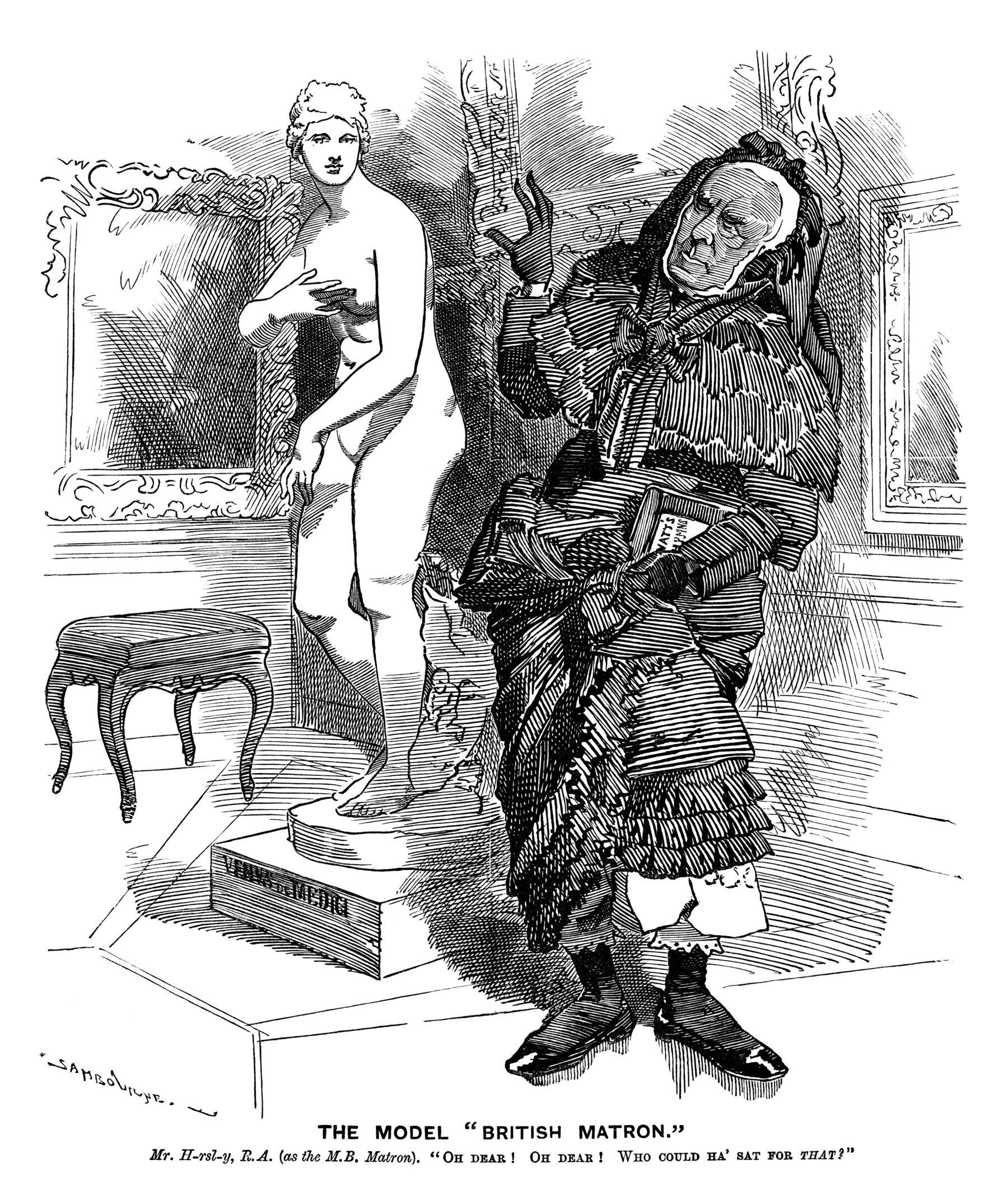

The Pall Mall Gazette described Whistler’s “pastel pictures” of 1885 as “very slight in themselves, of the female nude, dignified and graceful in line and charmingly chaste.”62 That final quality may have been intended to distinguish Whistler’s works from the more lubricious, life-size Venuses that had crowded the spring exhibitions. A letter to The Times in May from “A British Matron” protested “the display of nudity at the two principal galleries of modern art in London,” prompting a flurry of correspondence as artists and laypeople weighed in on the assumption—as one artist summarized the Matron’s point of view—“that purity and drapery are inseparable.”63 The controversy culminated with the Royal Academician John Callcott Horsley accusing his fellow artists of debasing young girls by persuading them “so to ignore their natural modesty, and quench their sense of true shame as to expose their nakedness before men, and thus destroy all that is pure and lovely in their womanhood.”64 Thus the British Matron’s moral outrage was appended to a plea for social reform: behind every nude picture, Horsley averred, lay a woman posing naked for a pittance, scarcely better than a prostitute.

In a Punch cartoon by Edward Linley Sambourne (fig. 3.10), the priggish Horsley becomes the artist’s model, attired in bombazine to impersonate the anonymous author of the letter to The Times. Recoiling in horror from the Medici Venus, the Matron mutters, “Oh, dear! Oh, dear! Who could ha’ sat for that?”65 Models posing in the nude were not a recent phenomenon, Sambourne implies, and Whistler himself could hardly wait “to twit Horsley about the nude & his absurd onslaught on it,” as his friend Alan Cole noted in his diary.66

Figure 3.10: Edward Linley Sambourne (British, 1844–1910), “The Model ‘British Matron.’” Punch 89 (24 October 1885): 195. Image © Punch Cartoon Library / TopFoto.

The opportunity arose in December 1885, when Whistler’s own nearly nude figures went on display at the Society of British Artists. To the frame of one of them (probably Note in Violet and Green, fig. 3.8), he affixed a label imprinted, “Horsley soit qui mal y pense.” If now abstruse, the quip was readily understood in its time as a play on the Old Anglo-Norman motto of the chivalric Order of the Garter, Honi soit qui mal y pense, meaning, “Shame on anyone who thinks evil of it.” One journalist construed Whistler’s act as “an indignant protest against the idea that there is any immorality in the nude,”67 but the artist’s objection was more encompassing. He regarded the current debate as the extreme conclusion of the misguided conflation of art and morality that had long encumbered British culture. To Whistler, the nude female figure, far from representing immorality, embodied art in its purest, most liberated, and most impractical form.

In the end, the moral controversy incited by the British Matron had little effect on the production of the Victorian nude, as Alison Smith has argued, though it did lift the artist’s model “out of the private space of the studio and life class into the realm of public debate.”68 Until then, the model had remained effectively invisible in England. Respectable painters designed their studios with separate entrances so that models could come and go without being seen by other members of the household; and in the context of the paintings for which they posed, models were understood only in terms of the characters they impersonated. “They career gaily through all centuries and through all costumes,” Oscar Wilde wrote of London models, “and, like actors, are only interesting when they are not themselves.”69

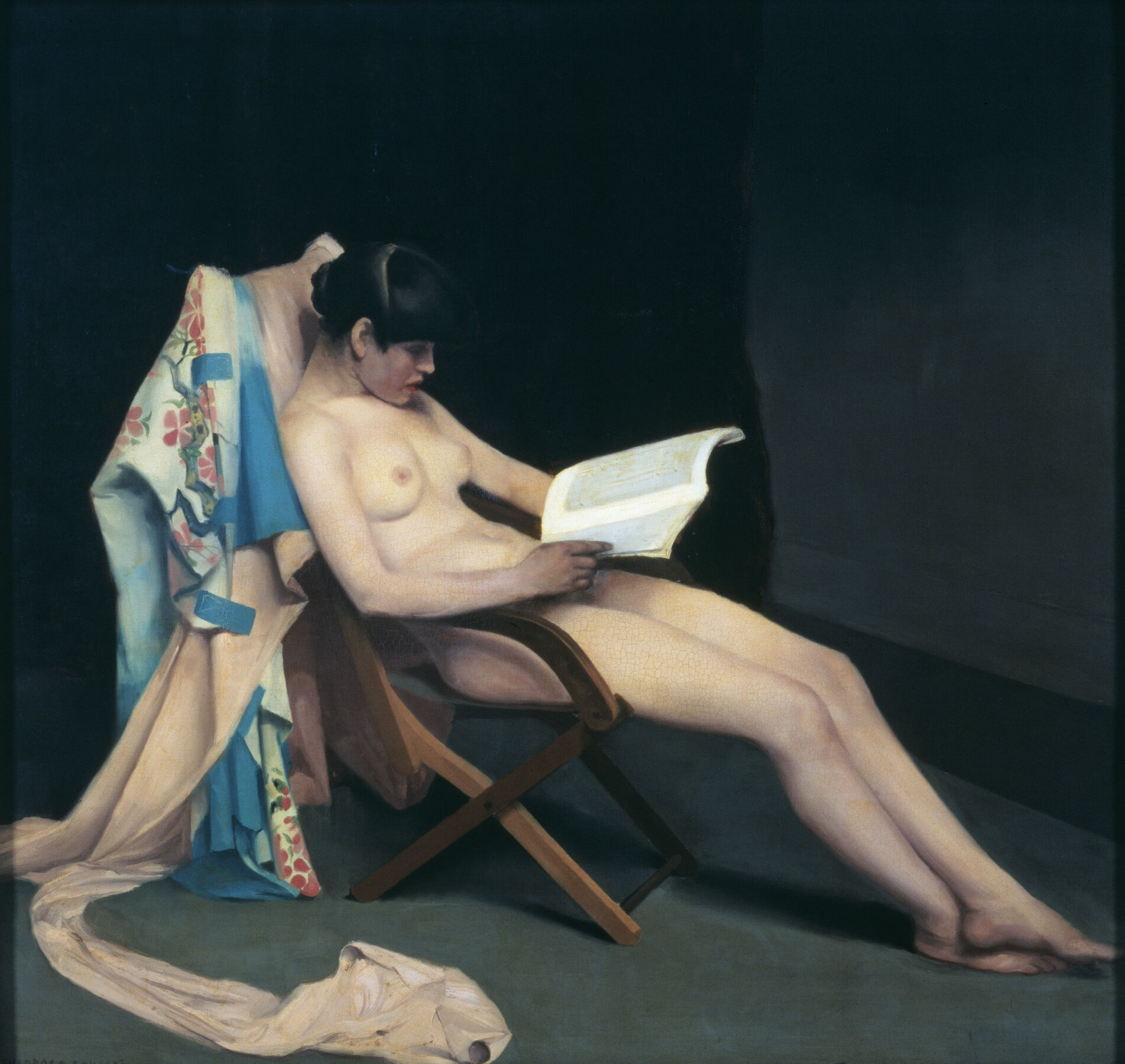

That paradigm was shattered in 1887, when The Reading Girl (fig. 3.11) was exhibited at the New English Art Club. The “girl” in Théodore Roussel’s painting is transparently the artist’s model, who has shed, for the moment, both her costume and her character. Although at work, she is not working, but is “buried,” as one critic remarked, “(but the British matron will regret to find not hidden) in the newspaper.” Although the painting has the polish of a French Salon nude, the model herself, with reddened hands and calloused feet, is shockingly real. “There has been no attempt to idealise the figure,” the critic continued. “It is simply a portrait of a rather underfed woman, who is content (at a shilling an hour) to be naked and not ashamed.”70

Figure 3.11: Théodore Roussel (English, born in France, 1847–1926), The Reading Girl, 1886–87. Oil on canvas, 152.7 x 162 cm (60.1 x 63.8 in.). Tate, London; Presented by Mrs. Walter Herriot and Miss R. Herriot in memory of the artist, 1927, N04361. Image © Tate.

Indeed, as with Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, exhibited some twenty-five years earlier, it was the model’s lack of shame that most unsettled the critics. As surely as her “underfed” form defied the prevailing preference for the plump, her apparent ease with her own nakedness—especially in the tacit presence of the artist—openly resisted the Victorian ideal of femininity. “No human being, we should imagine, could take any pleasure in such a picture as this,” wrote the Spectator. “It is a degradation of Art.”71

Whistler regarded The Reading Girl as “an extraordinary picture.”72 Roussel had been his “deferential disciple” since 1885,73 and during the years of their closest association they explored similar subjects, employed the same models, and nourished each other’s creativity. It has been suggested that Whistler’s lithograph The Little Nude Model, Reading (cat. no. 19) was made in response to Roussel’s painting, “adapting it to a more spontaneous medium and intimate scale,” which may certainly be the case, although the influence, it seems to me, could have flowed in either direction.74

Whistler’s “little” nude (relative, perhaps, to Roussel’s big one) perches on the edge of a low cabinet, attending to her reading. Apart from the headscarf (which Whistler always calls a cap), she wears not a stitch of clothing, though her discarded draperies are heaped behind her on the tabletop; the sketchy fireplace a few feet away implies the warmth that is the necessary condition for posing in the nude. Like the girl in Roussel’s painting, this one unwittingly draws attention to herself as a model, as distinct from the impersonal image of a generic body known simply as a figure.

Indeed, from this point forward, the word “model” slips into Whistler’s nomenclature, indicating the subtle shift in direction we can follow in his art; the small group of lithographs made in London just before 1890 depicts the model outside her customary role, a strategy that allows us to recognize the model behind the “figure.” Often, she is portrayed at rest—absorbed in a book (cat. no. 18), drinking tea (cat. no. 16), pulling on (or lifting off) her drapery (cat. no. 17) as though preparing for a session that has yet to begin. And even though her occupation depends on her ability to stand as still as a statue, Whistler sometimes shows her in motion, or at least alive to its potential. In The Dancing Girl (cat. no. 15), for example, the model gingerly points one toe, as though testing the waters; not yet prepared to abandon caution to the dance, she extends one arm to release a cascade of drapery.

What we do not see in these images is evidence of work, of models earning their hourly wage by holding inauthentic attitudes under the artist’s direction. “It is the secret of much of the artificiality of modern art,” wrote Oscar Wilde, “this constant posing of pretty people.” Whistler’s follower Mortimer Menpes confirms that the artist never prescribed a pose: “There was no pulling about of drapery, no gazing through arched hands, no special placing of the body.” Whistler’s unusually accommodating attitude may reflect his conviction that “industry in Art is a necessity—not a virtue,” as he wrote in 1884, “and any evidence of the same, in the production, is a blemish, not a quality; a proof, not of achievement, but of absolutely insufficient work, for work alone will efface the footsteps of work.”75 Not even the quasi-classical drapery that so often features in these works performs its ostensible function. Too transparent to conceal the body, too thin to keep it warm, and too generic to represent a costume or disguise, the gossamer fabric simply removes the model from the mundane. Formally, it enhances the contours of the nude body, a trick Whistler learned from his study of the Elgin Marbles. The “secret of repeated line,” as he calls the device in the “Ten O’Clock,” creates “the measured rhyme of lovely limb and draperies flowing in unison.”76

By doing away with poses that presume a plot and costumes that identify a character, Whistler allows the model to feature as an undisguised element in the process of art-making. To his way of thinking, a picture of a female model is a picture of nothing: a work of art without a subject, to be regarded on its own terms and appreciated for its own sake—a work of art about the work of art. His insubstantial little images thus threatened to dispel the grand illusion supporting the industry of Victorian subject painting. Edward J. Poynter, the estimable director of the National Gallery and soon-to-be president of the Royal Academy, confided to Whistler in 1894 that he had not read Trilby, the popular novel about an artist’s model in bohemian Paris, because, he said, “I generally dislike pictures of behind the scenes of an artist’s life being put before the public.”77 Whistler’s Tanagra lithographs—like Trilby, but in a lower key—offer up the rudiments of art, stripping away the mise-en-scène and laying bare the secrets of the studio.

The Master of the Lithograph

A lithograph is a work of art on paper, printed in ink, and existing in multiple examples, called impressions. Of the many processes for making prints, lithography is the most direct: the image is rendered on a flat stone slab just as a sketch is drawn on a piece of paper. The printing method depends on the simple concept that oil and water do not mix. The lithographic stone is prepared so that ink will adhere only to the greasy sketched lines of the image, while a film of water clings to the rest of the surface, preserving a pristine background. Under immense pressure, the image is transferred to sheets of dampened paper, though the resulting impressions rarely show signs of the force of gravity. An etching, in contrast, which is printed from an incised rather than a flat surface, always bears the mark of the metal plate where its sharp edges were impressed into the soft paper. In a lithograph, as if by magic, the drawing is replicated without leaving a trace of the effort involved in its production.78

Although lithography had always held potential as an artistic medium, from the time of its invention in the late eighteenth century it was used primarily as a cheap means of reproducing images, particularly in commercial advertisements. In England, it was Thomas Way (1836–1915), a professional printer with a family business in Covent Garden, who “made this matter of art printing his particular affair,” as Whistler wrote in retrospect, “and it is to him entirely that is due the revival of artistic lithography in England.”79 The two men became acquainted in 1877, when Whistler was already acknowledged as a virtuoso etcher and was also at the height of his powers as a painter. Within the year, Way had persuaded him to give artistic lithography a try, and to their mutual and continuing delight, “the master,” as Way called Whistler, discovered that the medium responded “to his most sensitive touch.” Although Whistler’s biographers the Pennells assert that the artist adopted lithography simply because it “happened to be the method of artistic expression which, at the time, met his need and mood,”80 it is likely that he was also influenced by his French colleagues, notably Henri Fantin-Latour and Edgar Degas, who were engaged in lithographic experiments of their own.81

Whistler’s first attempts were carried out in the traditional way, by drawing with a greasy lithographic crayon directly onto a porous limestone slab. The resulting prints, such as Study, 1879 (fig. 3.12), have the soft-edged look of charcoal sketches, in contrast to the precise, pen-and-ink appearance of an etching such as The Model Resting (Draped Model) (see fig. 3.2). The classically draped figure depicted in Study, the only early lithograph related to the Tanagra series, stands in a highly contrived, contrapposto pose. Her head, in almost perfect profile, turns toward the artist’s signature butterfly, which hovers conspicuously just above her elegantly disposed left hand. The butterfly cipher, originally fashioned as a monogram, had been used in rudimental form in Standing Nude, 1869 (see fig. 3.1); it was to assume particular importance in the formally concise lithographs, and Whistler would be fastidious about its placement and proportions.

Figure 3.12: James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903), Study, 1879 (C.19). Lithograph on a prepared half-tint ground, 26 x 16.5 cm (10 1/4 x 6 1/2 in.). The Art Institute of Chicago; Bryan Lathrop Collection, 1934.521. Image: Public domain via CC0.

After Study, the artist abandoned his efforts in lithography for nearly a decade. In 1887, when he resumed the medium, he employed the more convenient method of transfer lithography, which his contemporaries in France had also adopted. With that technique, he could draw on specially treated paper that allowed the seamless transfer of the image to the stone. In the process, the composition was reversed, so that when an impression was printed, the original orientation of the image was restored. Despite being one step further removed from the stone, the transfer lithograph was even closer to the artist’s original than a print made in the traditional manner. It was partly for that reason that Camille Corot advanced transfer lithography as the ideal method for producing multiples of drawings.82 And “from the artist’s point of view,” as Lochnan has remarked, “a simpler method of printmaking could not be conceived.”83

Nevertheless, it took time for Whistler to master the process. The commercially produced, mechanically grained transfer paper was disagreeable to work with; mistakes were hard to spot and tedious to correct. Because an image drawn with lithographic crayon is visible only as a faint stain on transfer paper, stray lines and other imperfections become apparent only when a proof impression is pulled from the press.84 In Model Draping (cat. no. 17), for example, Whistler neglected to remove the horizontal line at the model’s feet used to block out the square column of her drapery; in The Novel: Girl Reading (cat. no. 18), the viewer can barely make out the model’s facial features, and the delineation of her drapery gives way, around the middle, to what can only be considered scribbling. “There is nothing more difficult in art than to draw the figure,” Elizabeth Pennell points out in her article on Whistler as “Master of the Lithograph,” “and the difficulty is increased a hundredfold when the medium is as inexorable as the lithographic chalk.”85

The charm of these images easily conceals their defects: only under close examination, for instance, do we discover in The Horoscope (cat. no. 16) that the model may have three legs entangled in her drapery. “That was a very early and bungling struggle,” Whistler later had occasion to explain, “with the difficulties of a new material.”86 Indeed, Whistler was so disheartened by his initial efforts—the first of the Tanagra lithographs—that he instructed Way, by then assisted by his son, Thomas R. Way, to expunge them all from their stones. Happily, this did not occur, and impressions were eventually printed with the artist’s approval. In Way’s estimation, the salvaged prints were among Whistler’s finest—“of extreme delicacy, yet with a certainty of line unsurpassed during any other period”—and the artist himself named three of them among the four images on the Tanagra theme that he considered “most representative—and according to my own choice of quality.”87 The aspect of ease that distinguishes the Tanagra lithographs was therefore obtained only through unremitting effort: “The work of the master,” Whistler maintained, “reeks not of the sweat of the brow.”88

According to T. R. Way, Whistler might never have persevered were it not for his wife, “herself an artist of real skill,” who took a particular interest in his experiments with lithography, “as though she felt it offered him a field where he might surpass his reputation in any other of his works.”89 Like so many women of her time who managed to overcome cultural expectations to become artists, Beatrice (later Beatrix) Philip (1856–1896) was first the daughter and then the wife of one. Her father was the sculptor John Birnie Philip, who died in 1875; her husband, whom she married the following year, at age eighteen, was the architect and “aesthetic polymath” Edward W. Godwin.90 Among her earliest works were designs for the carved bricks embellishing Godwin’s Queen Anne-style buildings; she also designed wallpaper and ceramic tiles, and painted decorative panels for art furniture.91

In 1885, Whistler—one of Godwin’s closest friends—happened to see a small figure painting in oil by Beatrix and was so impressed, Godwin proudly reported, that “he took it away to show as the work of a pupil of his.” Her painting was exhibited that year at the Society of British Artists, and even though she had previously shown works under her own name (or rather her husband’s, as Mrs. E. W. Godwin), Beatrix was persuaded, presumably by Whistler himself, to adopt the pseudonym Rix Birnie, which disguised both her gender and her identity. She was also identified in the catalogue as Whistler’s pupil, even though she may not yet have been.92

Beatrix Godwin was, however, spending many hours in the artist’s studio posing for her portrait, Harmony in Red: Lamplight, in which she gazes at the artist with loving eyes. The Godwins were by then estranged. His health had been failing since 1885, and he died intestate in October 1886, leaving his widow and their eleven-year-old son, Teddy, financially insecure. Ostensibly in recognition of Edward Godwin’s “great services to art in England,” Whistler started a petition to raise funds “for advance to Mrs. Godwin, to enable her to take an assured position as an artist.”93 Perhaps supported by the magnanimity of her late husband’s friends, Beatrix pursued further artistic training, briefly in Paris but also in London, where Whistler taught her how to etch. By 1888, she was recognized in the press as “a remarkably clever artist and decorative draughtswoman,” whose talents had only ripened “under the influence of the great James McNeill.”94

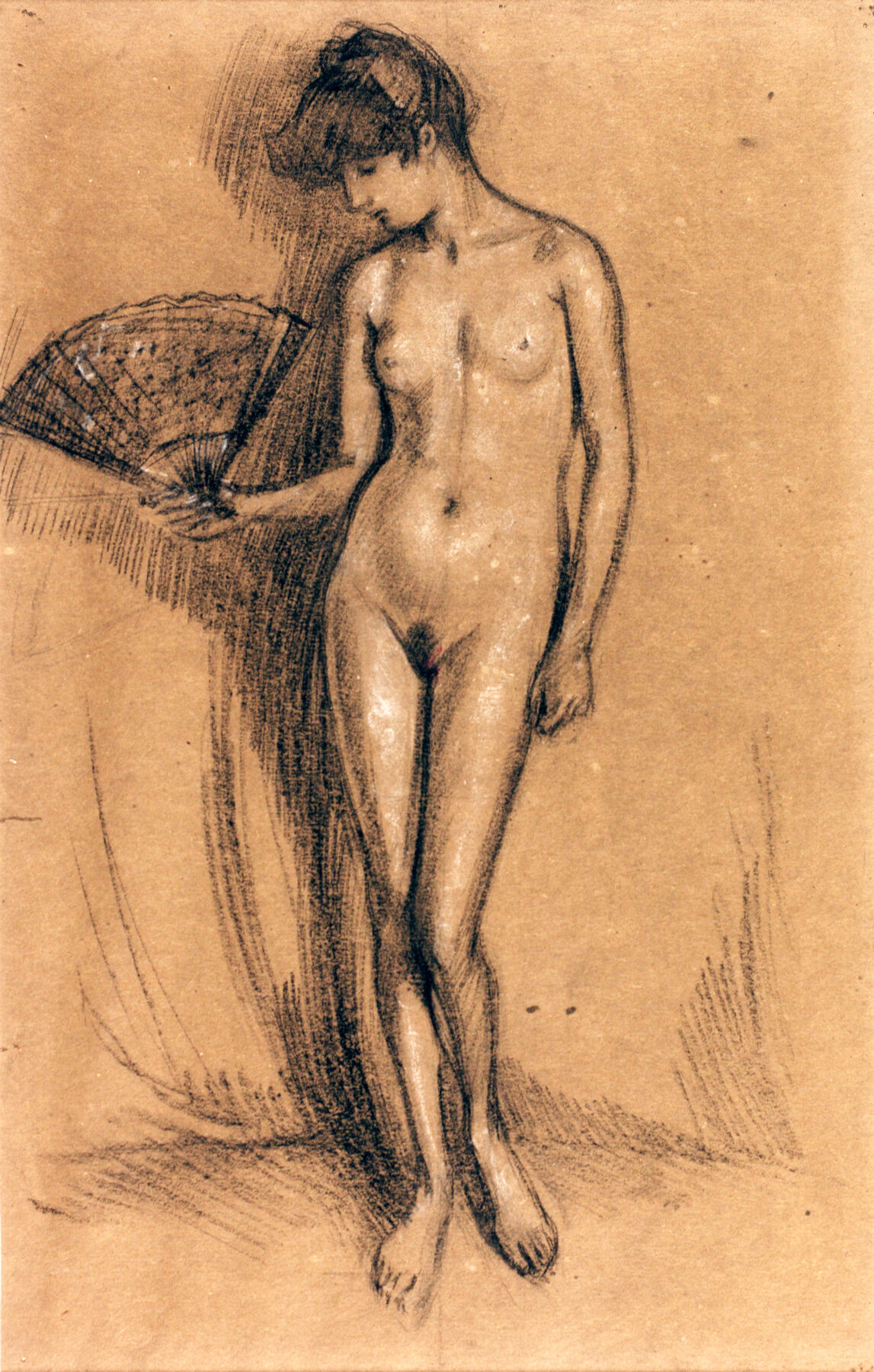

As part of her re-education, Beatrix Godwin made numerous studies from the nude figure, working on a larger scale and in a more naturalistic style than her influential mentor. The two artists appear to have worked companionably in the studio, sometimes from the same model. Beatrix’s Nude woman with an open fan (fig. 3.13) might be compared, for example, to Whistler’s The Tall Flower. The model’s pose is only slightly different, but Whistler’s treatment of the nude, perhaps owing to the watercolor medium, is the more delicate and tentative. Beatrix’s drawing is fluent and assured. The model holds a fully opened fan by her side, as if to indicate that nothing was to be concealed from view; her downcast eyes imply her modesty, lending a touch of irony to Beatrix’s frank image of female nudity.

Figure 3.13: Beatrix Whistler (British, 1857–1896), Nude woman with an open fan, ca. 1887. Black and white chalk on brown paper, 56.5 x 36 cm (22.2 x 14.2 in.). Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow, Donated by Rosalind B. Philip (1935), GLAHA:46542. Image © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow.

The model for both works was Rose Pettigrew (1872–1958) (fig. 3.14), the youngest of three sisters who came to London from Portsmouth in 1884, after their widowed mother was persuaded that respectable artists would pay well to paint them. Their first engagement was with the Royal Academician J. E. Millais, who portrayed all three in An Idyll of 1745; after that, they never wanted for work and soon became, in Rosie’s words, “the best paid posers in England.” We have seen Hetty, the eldest, as the model for Roussel’s Reading Girl (fig. 3.11). She and Lily posed together in a series of paintings by John William Godward, including Mischief and Repose (Lily is Mischief), and for a series of photographs by the Punch cartoonist Linley Sambourne, who sometimes posed them in the nude, relying on the images as “a very useful adjunct to art” when live models were unavailable.95

Figure 3.14: Photograph of Rose Amy Pettigrew (1872–1958), ca. 1889. Image courtesy of The Warner Family.

All three Pettigrews started working for Whistler around 1887, a date we can deduce from Rosie’s memoirs, in which she slyly mentions knowing “several of Whistler’s ‘wives.’” This suggests that the Pettigrews’ early sittings took place while Maud Franklin, the artist’s longtime model and companion, who liked to be called Mrs. Whistler, was still in the picture.96 The Pettigrews’ arrival in the studio coincides with the commencement of the Tanagra lithographs: it was almost certainly Rosie who sat, at age fifteen, for The Little Nude Model, Reading.97 She also posed for Peach Blossom (cat. no. 48), Beatrix Godwin’s more conventional and ladylike rendition of Whistler’s theme, in which the model reads her book while fully clothed and seated in a proper chair. The peach-colored dress (“pink, trimmed with mauve”) that in Whistlerian fashion sets the picture’s color scheme was probably among the “lovely little frocks” that Beatrix made for Rosie.98 “The wife I really loved,” the model wrote, “was the real one.”99

Whistler and Beatrix Godwin were married on August 11, 1888. At age thirty-one, Beatrix had been a widow for less than two years, but she was said to be bohemian, like her second husband (then fifty-six), which implies that neither was particularly concerned about the propriety of their relationship. They had considered marriage only “in a vague sort of way” before their friend Henry Labouchère intervened and set the date, arranging for a quiet wedding when Maud Franklin would be out of town. “Half the artist world would have gone to see Mr. Whistler married,” one newspaper reported, “if they had but known of it.”100 The Whistlers settled into a studio flat in Tower House, one of the Tite Street buildings that Godwin had designed.

Beatrix fixed her affections on Rosie Pettigrew, perhaps because her own child was away at school. “Mrs. Whistler loved me as much as I loved her,” writes Rosie, adding, “She wanted to adopt me, but mother wouldn’t hear of it.”101 From the young model’s recollection of Mrs. Whistler being ever present when she posed, “to my great joy,” we are given a glimpse of Whistler’s studio—not at all the transactional space of popular imagination, where innocent girls were regularly exploited by aggressive painters, but a comfortable environment contentedly occupied by three young women and presided over by the artist’s wife, whose maternal care modulated Whistler’s aesthetic detachment. His own presence in the studio is marked only by his butterfly signature, now artfully intertwined with Beatrix’s trefoil monogram. The lithographs created during the years of their marriage, particularly the figural works we call Tanagras, appear to be the emanations of a jubilant state of mind, for as Whistler declared in the “Ten O’Clock,” “Art and Joy go together.”102

The Beautiful Rosies

The polychrome decoration of Tanagra figurines that appears to have inspired Whistler’s pastels in the 1880s may also account for his experiments in color lithography, which occupied his attention for three years, beginning late in 1890. His ambition was to find a way to supersede the conventional methods of chromolithography, in which primary colors were overlaid to produce secondary hues that often ended up leaden and murky. Whistler aspired to the clarity of color found in Japanese woodblock prints, where brilliant hues were juxtaposed, “as in a mosaic.”103 Whistler’s method, according to Joseph Pennell, was to begin with a single drawing on transfer paper, printed in the usual way; he then would make as many drawings as there were to be colors in the final print, transparent overlays keyed to the master (or “keystone”) drawing. After that, the tedium began: “Those parts of the drawing that are not wanted, that is all but the red, for example, must be scratched or etched away, and the same for the other colours.”104 Finally, for each impression, a sheet of paper (antique or Japanese, carefully selected by Whistler himself) would pass through the press as many times as there were colors to be added.

His first attempt, Figure Study in Colors (cat. nos. 20 and 21), printed by Thomas Way, is a straightforward image of a draped model sitting uncharacteristically still, her hands clasped around one knee, as though waiting patiently for something—anything—to begin. Whistler inadvertently bungled the process, making two of the drawings on the wrong side of the paper, and he gave up in exasperation after a handful of partially colored impressions emerged from the press.105

When he finally had the heart to try again, Whistler sought an experienced color printer in Paris, where other artists of the Belle Époque, such as Jules Chéret, had taken up the process for poster art. On a brief trip to the Continent in June 1891, Whistler met Henry Belfond, whom he considered the only person in Paris to print “with intelligence and feeling.”106 At Belfond’s shop in the rue Gaillon, Whistler discovered a new kind of transfer paper, poor in quality but rich in potential, on which he made several drawings that were probably intended to be developed into color lithographs. The patchy lines in Nude Model, Standing (cat. no. 24), for example, indicate the difficulty of drawing on the finely grained paper, with the chalk skipping across the slippery surface. Although he abandoned the design, a pastel made around the same time, Blue Girl (cat. no. 42), gives us an idea of how it might have looked if Whistler taken the lithograph further. Draped Model, Dancing (cat. no. 25), another practice lithograph, shows a similarly irregular quality of line, yet the dancer’s body and drapery are depicted “with equal evanescence,” as Sarah Kelly notes, “mingling and obscuring her form with that of the sheer fabric.”107 Both prints, though technical failures, possess a beauty as fragile and imperfect as the delicate transfer paper on which they were drawn.

A few months later, Whistler returned to Paris for a longer stay, and he and Belfond worked out a system—or “arrived at a solution,” as he later phrased it, “of the uncertainties of colours in lithography.”108 The artist would stand beside the press, mixing the oily inks himself, adjusting the hues according to the shade of the paper used for printing, and applying the color to the stone “in the most personal manner, delicately, exquisitely.”109 That deft touch, opposite in effect to the heavy-handed application of commercial chromolithographs, especially distinguishes Draped Figure, Standing (cat. nos. 22 and 23). Drawn in France from a model identified only as “Tootsie,” the figure is reminiscent of a Tanagra figurine; she pulls her drapery over her head and touches her hair in a gesture associated with the goddess Aphrodite (fig. 3.15).110

Figure 3.15: Aphrodite, Boeotia, first half of the 4th century BCE. Terracotta, 24.7 x 9.7 x 5.5 cm (9.7 x 3.6 x 2.2 in.). National Museums of Berlin, Antiquities Collection / Johannes Laurentius. Image: Public domain via CC BY-SA 4.0.

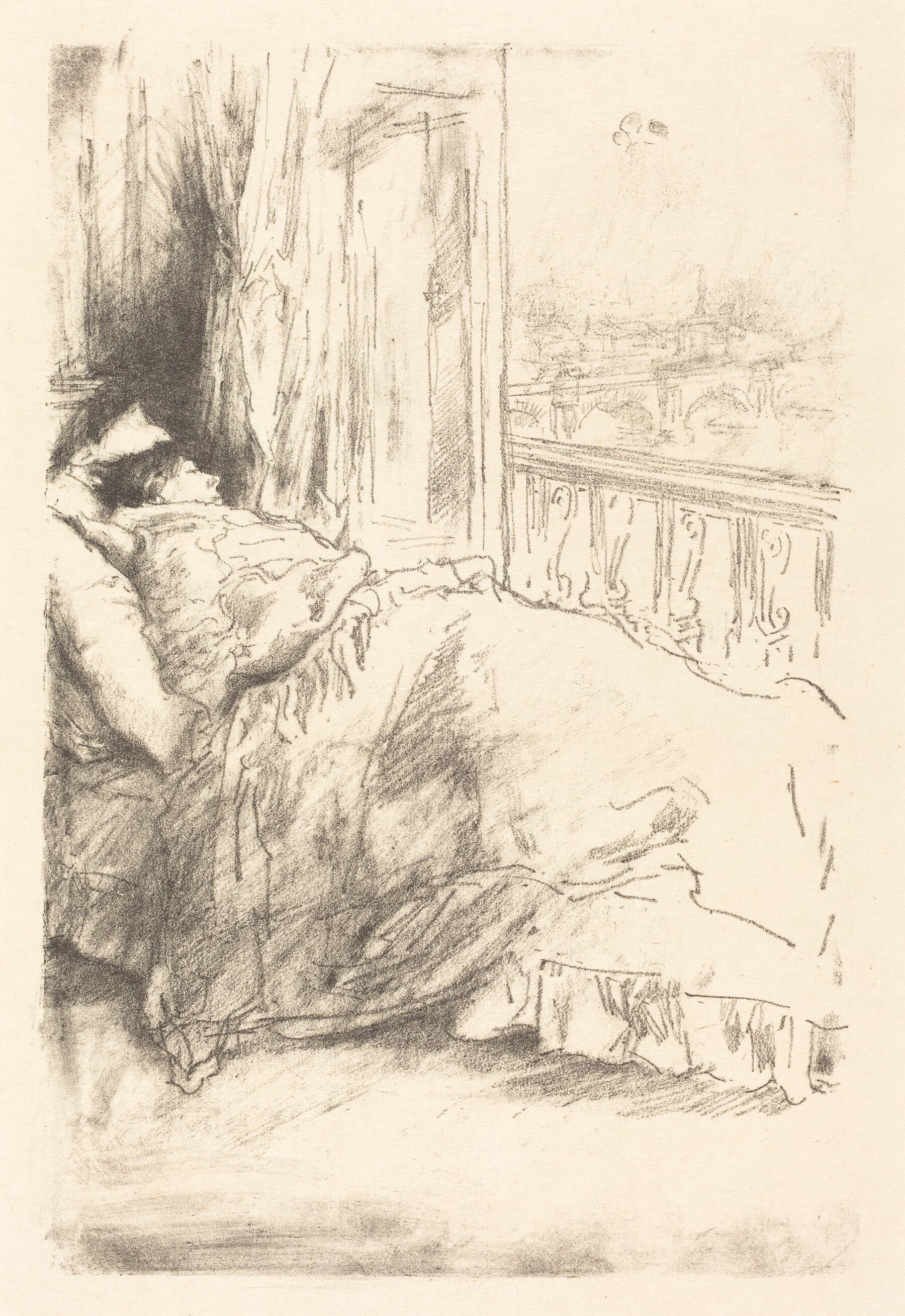

The enhancement with color completes what Nicholas Burry Smale aptly describes as “the realist subversion of the ideal.”111 A more complicated image, Draped Figure, Reclining, demonstrates Whistler’s fastidious attention to nuances of color; each impression represents a variation in tonal arrangement (cat. nos. 30 and 31). Although printed in Paris, the image had been drawn in London from one of the Pettigrews,112 who does not just recline in this print, as the title says, but falls asleep. Originally called La belle dame paresseuse (“the lovely, lazy lady”), the lithograph is a further expression of the model not-at-work, the embodiment of an art whose sole purpose is to look beautiful.113

In a related color lithograph titled Lady and Child (fig. 3.16) (not, it should be noted, “Mother and Child”), we encounter a new addition to the family of Pettigrew models: Edith Gertrude, born in March 1889, the fourth child of the sisters’ elder brother Alfred. The little girl in her ruffled bonnet is propped on the studio sofa with a yellow toy of some sort in her lap; she gazes steadily at the artist while her aunt, nearly unrecognizable in street clothes and a bergère hat, takes the opportunity to rest her eyes. In Cameo, No. 1 (cat. no. 39), a rare etching from this period that was originally titled Little Edith,114 it is the baby who is coaxed to nap by her loving aunt, all draped up and ready for work; in Cameo, No. 2 (cat. no. 40), the baby sleeps. Whistler also made several drawings of Edith with her Pettigrew relation (probably Rosie) on transfer paper, presumably meant as keystone drawings for color prints. As with the single-figure Tanagra lithographs, the models appear to have been free to do whatever they pleased—play, sit, cuddle, or sleep—while the artist waited for the pose that formed the picture.

Figure 3.16: James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903), Lady and Child (C.55), 1892. Color lithograph, 16 x 25.7 cm (6 5/16 x 10 1/8 in.). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Rosenwald Collection, 1946.21.370. Image: Public domain.

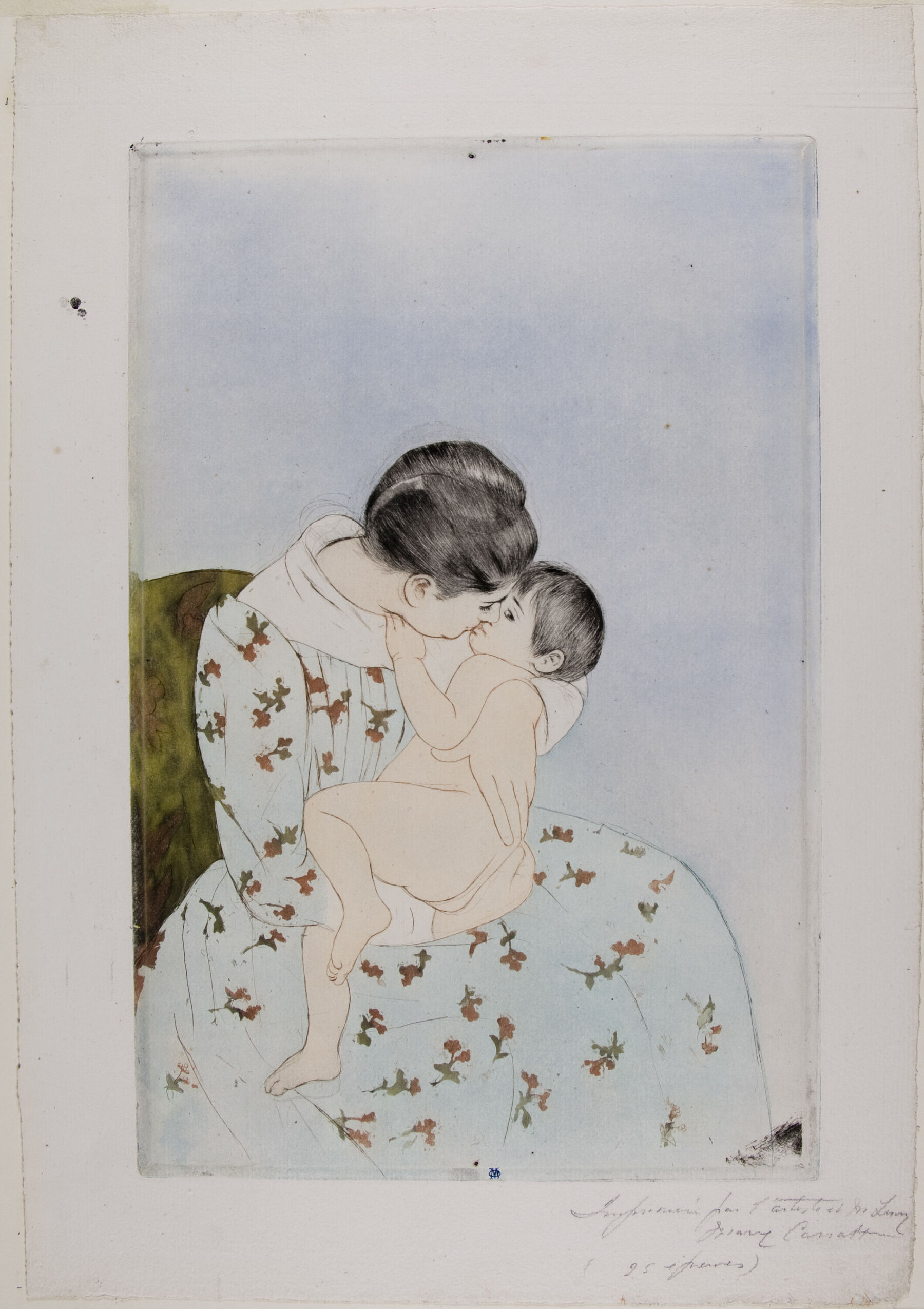

The first of the four transfer lithographs titled Mother and Child (cat. no. 26) can be dated to June 1891 because the old papier viennois on which it is drawn makes it contemporary with the two Cameo etchings. The other three, all horizontal, must have been made later in the year, as they are drawn on the tissue-thin papier végétal that Whistler brought back with him that summer from Paris (cat. nos. 27, 28, and 29). Whistler fell out with Belfond before the drawings could be developed into color lithographs and they were put away, but not forgotten. At Beatrix’s request, the drawings were retrieved in 1895, and impressions were printed in London by the Ways with varying degrees of success. Only then was the perfunctory title Mother and Child assigned to every picture in the series.

Had they evolved as originally intended, the images would more closely resemble Whistler’s pastels on the same theme, such as Rose and Red: The Little Pink Cap, The Purple Cap (fig. 3.17), The Pearl, The Shell, and they would probably bear titles evocative of visual effects, not indicative of generic subjects. The serial title makes it easy to overlook the individual qualities of the lithographs, but Pennell, probably encouraged by Whistler, singled out the second of the four (cat. no. 28) in her Scribner’s article. Simply titled Mother and Child, it forms the headpiece and is praised in terms both technical and art-historical, as being “instinct with maternal devotion as the Madonnas of Bellini or Fra Angelico, the plump nakedness of the child a marvel of masterly execution, of eloquent form.”115

Figure 3.17: James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834-1903), The Purple Cap (M. 1287), ca. 1890. Chalk and pastel on grey paper, 27.6 x 18.1 cm (10 7/8 x 7 1/8 in.). National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Freer Collection, Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1902.111a-c. Image courtesy of the National Museum of Asian Art.

How can we account for the efflorescence of this sentimental theme in nearly every medium of Whistler’s practice during this late period of his career? It is possible that he found inspiration in the Tanagras called kourotrophoi, or “child nurturers,” mortal women or divinities shown with an infant or small child (cat. no. 7). “The Tanagra potter was particularly happy in his renderings of figures or scenes in which gentle grace predominates,” observed the Victorian writer Caroline A. Hutton, citing an example in the British Museum possessed of “all the sweet serenity of a mediæval Madonna.” (That figurine has been revealed to be a reconstruction, with a pretty young head appended to the body of an elderly nursemaid.)116

More often advanced as precedents for Whistler’s lithographic theme are the comparatively ornate statuettes of Aphrodite and Eros, particularly an example in the Ionides collection in which the figures are recumbent.117 (Although it would not have mattered to Whistler, that now unlocated figurine was almost certainly a modern forgery.)118 According to Olivier Rayet, the coroplasts were simply developing a theme frequently explored by poets of the fourth and third centuries, of love (in the form of Eros) attempting to fly away from the beautiful young woman who tries to hold onto it. One example shown at the 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris, in which a seated draped figure plays with the naked baby in her lap (cat. no. 50), might plausibly relate to Whistler’s Mother and Child, No. 1 (cat. no. 26).119

Although Whistler was purging subject matter from his art, in the Tanagra renditions of the mother-and-child theme he may have recognized a relevant reconciliation of the human with the divine. Marcus Huish, in 1900, imagines a Tanagra potter charged with representing the “Goddess Mother” but finding little inspiration in the traditional type, while “in his own house, he had in his wife and infant one surpassing anything that he could imagine. If he possessed any artistic sense, he would be moved to translate this into clay.”120 In the same way, perhaps, Whistler recognized the mortal equivalents of his own muse, the being he considers the goddess of art, in the blithe young models who had the run of his studio.

Whistler might also have looked for inspiration to contemporary works for inspiration. His fellow American expatriate Mary Cassatt, for example, was experimenting with color printing at this very moment, and an aquatint such as After the Bath (fig. 3.18) approximates the quiet sensuality of Whistler’s works.121 It is important to recognize that Cassatt’s figures, like Whistler’s, were based on hired models who were not necessarily related to the children they appear to mother. The maternal theme was a culturally appropriate way to express ideas about artistic creativity, especially for women artists, though Whistler himself once relied on the metaphor to describe the process of art-making: “It’s the pain of giving birth!”122 But the overarching theme of Whistler’s imagery, as Katharine Lochnan acknowledged, is probably not motherhood in itself, but the notion of “woman as nurturer,”123 the Greek kourotrophos. If we accept Whistler’s Tanagra images as the embodiments, or evocations, of his muse—the “loving and fruitful” goddess described in the “Ten O’Clock”124—then the infant cared for so tenderly in the sheltered space of the studio may be considered the exquisite creation of the artist’s hand, the work of art itself.

Figure 3.18: Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926), After the Bath, 1890–91. Color aquatint and drypoint from two plates on ivory laid paper, 34.6 x 28.8 cm (13 5/8 x 11 3/8 in.). The Art Institute of Chicago; Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1932.1286. Image: Public domain via CC0.

However they might have been understood by Whistler’s contemporaries, these charming images would seem the most likely of all his works to appeal to popular taste. Yet Whistler rarely exhibited the mother-and-child pastels, and he printed the related lithographs in tiny editions. Of the handful that were sold, nearly all went to Charles Lang Freer, his highly sympathetic patron in Detroit. The majority remained in Whistler’s studio at the time of his death.

Whistler and Beatrix seem to have regarded these works as a kind of joint endeavor, like aesthetic offspring, perhaps inspired by the ambiance of affection they created in the studio. To them, the images were highly personal, deeply private, and deliberately recondite. We see this in the letters written by the artist during his quick trip to Paris in June 1891, while the series was still in progress. Whistler reports to Beatrix on his visit to the gallery of Paul Durand-Ruel to view recent works by his Parisian contemporaries. “There is a little room full of Renoirs—You have no idea! I don’t know what has happened to the eyes of every body—The things are simply childish—and a Degas absolutely shameful!” Had they been together, he wrote to his wife, they would have held hands and summoned the memory of “the beautiful Rosies,” or Pettigrew pastels, presumably as a defense against bad art. Because they were apart, Whistler advised Beatrix to retrieve the delicate works from the cabinet in the studio where they were kept and handle them with care. “Take the two drawers, just as they are, and carry them up stairs—don’t let them be shaken, and cover them over with a little drapery and wait till I come back—We have no idea how precious they are!”125

The Pinnacle of Fame

For those who know Whistler only as the author of the square and somber portrait of his mother, the drawings of lithe young women entwined with naked babies can be difficult to assimilate. The puzzle is only compounded when we learn that Arrangement in Grey and Black (“Whistler’s Mother”) was in the Whistlers’ new London home at 21 Cheyne Walk in 1891, while the “Rosies” were in progress. “It was hung rather low,” their parlor maid recollected, “and looked for all the world like life and seemed too natural for a picture.”126 Yet Whistler’s variations on the theme of motherhood, created decades apart, in diverse media and on a vastly different scale, identically express his wish to liberate art from the expectations of convention. The portrait of his mother, as he explained around this time to the artist Henry Tonks, naturally possessed interest for him, “as he was very fond of her.” To anyone else, Whistler said, shifting the emphasis from sentimental subject to formal abstraction, “its beauty could be just as well seen if they looked at it upside down.”127

Whistler’s Mother was the key that unlocked the artist’s lasting renown. In November 1891, it was purchased for the Luxembourg in Paris, the national collection of works by living artists, which destined the portrait, eventually, for the Louvre. Its acquisition by the French state set off a series of exhibitions and accolades that finally secured Whistler’s stature as an artist. As du Maurier noted in Trilby, “He is now perched on such a topping pinnacle (of fame and notoriety combined) that people can stare at him from two hemispheres at once.”128 Responding to the demands of his rising reputation, Whistler was also living in two cities at once, making frequent trips across the English Channel, but by March 1892, he was ready to leave England for good, as his “strongest art sympathies,” he announced, were centered in Paris.129 In England that year, Whistler’s French success was regarded with suspicion until it was categorically confirmed by the stunning retrospective of his paintings, Nocturnes, Marines, and Chevalet Pieces, at the Goupil Gallery. As D. C. Thomson wrote to Beatrix Whistler, then in Paris, “To those who have eyes to see, & fortunately they are increasing in number, the collection is the most notable event that has taken place in London for many many years & it will stand out for all future times as one of the epochs of art in this country.”130

Seeking out the artist at the Goupil exhibition, a reporter for the Illustrated London News referred to a rumor that Whistler had “invented a new process of lithography.” Whistler demurred, “I am simply busy with some coloured lithographs, which will be seen by-and-bye.” The “new process,” he said, was only “a return to simplicity,”131 but that may have been wishful thinking, for the permanent move to Paris had greatly complicated Whistler’s lithographic practice. While he continued working with Belfond on color lithographs, he relied on the Ways to print the monochrome impressions: “These things are of great delicacy, and I could not dream of running risks in other hands.”132 Rolled up in periodicals for protection, Whistler’s transfer-paper drawings were regularly posted to London, along with extensive instructions for the Ways: “Of course more margin at the bottom than at the top. About paper—the white you sent, is rather too white.”133 Their richly detailed correspondence illuminates what T. R. Way regarded as “one long series of experiments, so frequently did he vary his materials and his manner of using them.”134

The most consequential development in this period may have been Whistler’s adoption of the crayon estompe, or “stump,” a tool made of paper wound tightly into a stick, or stump, and suffused with tusche, a liquid drawing medium. Whistler discovered that the stump imparted a particular richness to his drawings, “a certain velvety daintiness—quite unlike anything I have ever seen.” The effect is especially striking in a pair of lithographs from 1893, referred to by the artist in typical shorthand as “the lying down figure” (cat. no. 34) and “the sitting figure” (cat. no. 33). Both were drawn from the same model, a young Italian named Carmen Rossi (born around 1878)—“a nice little Rosie,” as Whistler described her to Beatrix—who had turned up at Whistler’s Paris studio one day in January 1892. Together, the lithographs mark an important advance in Whistler’s process. “I am getting to use the stump just like a brush,” he informed Way, “and the work is beginning to have the mystery in execution of a painting.”135

In Nude Model, Reclining (cat. no. 34), the heavy somnolence that had suffused Draped Figure Reclining (cat. no. 31), the color lithograph from the previous year, has given way to an atmosphere charged with possibility. The model’s quirky pose—head supported by one elbow while the other arm tents the drapery above one hip—could not have been maintained for long: as MacDonald has observed, “The brevity of this glimpse of the naked body is emphasized by the conciseness of the technique.”136 The unusual disposition of the model’s legs may derive from a painting in the National Gallery, Tintoretto’s Origin of the Milky Way, of which Whistler kept photographs in the studio.137 Although it is difficult to reconcile the quiet languor of Whistler's image with the frenzy of Tintoretto’s scene—Hera’s hectic suckling of the infant Herakles just before she repels him in pain and spews divine milk across the heavens to accidentally create the Milky Way—the visual quotation may have been meant especially for Beatrix, as The Origin of the Milky Way was her favorite painting.138

In the second of the pair (cat no. 32), the model has risen to a seated position on the Empire-style sofa, though she seems even less alert than when she was recumbent. Seated Tanagra figurines are rare, but Whistler’s Draped Figure, Seated may have been inspired by a lovely figurine purchased for the Louvre in 1876 (since identified as a forgery) of a woman seated on a rock. As one contemporary scholar helpfully pointed out, “rocks cannot have been used as furniture among the Greeks,” so the rustic setting may identify the figure as a muse at rest in the natural world.139 Whistler’s draped figure is more luxuriously situated in the studio, with the suggestion of a folding screen behind the couch. Her body forms a sturdy pyramid, though one of her legs, slightly bent, suggests that she might attempt, unsteadily, to stand. In a telling visual echo of the Tanagra’s gracefully bowed head, the dark halo of the modern model’s hair and scarf shadows her downcast eyes, conjuring a sense of the semi-conscious, that hazy borderland between wakefulness and sleep, making her appear, like the terracotta, as if lost in a dream.

This was the figure that Whistler selected to represent his art in a portfolio of prints called L’Estampe originale. The publisher, André Marty, was the leading advocate of artistic lithography in France, and even though, as Whistler explained to T. R. Way, “there is as usual no money in the matter for me,” the lithograph would appear in the distinguished company of works by such artists as Pierre Puvis de Chavannes and Félix Bracquemond—and so, Whistler decided, “Let us be very swell among them all.” Marty himself collected Whistler’s drawing in Paris and hand-delivered it to the Ways in London, also providing a ream of gampi torinoko, the sturdy Japanese paper on which a hundred impressions were printed. The resulting proofs, according to the artist, were “absolutely perfect.”140

As published in L’Estampe originale (cat. no. 33), the lithograph was unaccountably called Danseuse (“Dancer”); perhaps Georges Vicaire, who catalogued the prints in 1897, detected an affinity with a Tanagra dancer, such as the Danseuse Titeux (cat. no. 1), and imagined her in repose. Whistler himself gave one title to the lithograph in 1894—The Seated Draped Figure—when he sent an impression to London for exhibition at the Grafton Gallery, and quite another when the lithograph went on view with the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts: La Songeuse, or “Daydreamer.”141 In fin de siècle France, that title positioned Whistler decisively within the Symbolist circle. French Symbolism was in many ways aligned with the aestheticism that Whistler had long espoused. The movement was a reaction to the art of description that had prevailed throughout the nineteenth century in the various forms of naturalism, Realism, and Impressionism. Seeking something more elusive—essence rather than substance or even appearance—the Symbolists fashioned complex metaphors to suggest (but never describe) the faint correspondences they detected between the material and the spiritual. Their esoteric art was ambiguous by design.142

Stéphane Mallarmé (1842–1898), the poet credited with endowing the Symbolist movement “with a sense of the mysterious and ineffable,” had provided a French translation of Whistler’s “Ten O’Clock” in 1888, affirming his own sympathy with the artist’s aestheticist vision.143 In return—as a symbol, so to speak, of their consonant “aesthetic of implication”—Whistler presented Mallarmé with an impression of The Dancing Girl (cat. no. 15),144 one of the first of his Tanagra lithographs. From the Symbolist point of view, the dance is the ideal art form, “a purely visual text that is fleeting and transitory,” as Sarah Kelly observes, which finds a parallel in Whistler’s ephemeral lithographs. Moreover, as an instinctive, spontaneous expression of joy, dance is an apposite symbol of the creative impulse,145 and Mallarmé reciprocated with “Billet à Whistler,” a sonnet in which art is personified as a dancer twirling through space, “a muslin whirlwind.”146

Imbued with art and friendship, Whistler’s contented Parisian life found expression in his lithographs—notably the images of his muse, who regularly communed with the artist at his new studio in Montparnasse (fig. 3.19). On the sixth floor of a modern building in the old-world street of Notre-Dame-des-Champs, the studio was “really perhaps the finest thing of the kind I have ever seen,” Whistler informed his sister-in-law.147 Its perfection was confirmed by Robert Sherard, the English journalist who visited the artist in Paris in 1893, though he was surprised to discover that apart from the printing press, “the only commercial-looking thing in all the place,” there were no signs of work in the studio, “no easel visible, not one palette, none of the charming litter of the art.”148 It was as if Whistler were encouraging the production of art by denying the existence of labor, effacing “the footsteps of work” not only from his artistic inventions, but from his professional domain. The house in the rue du Bac, too, where he and Beatrix had taken up residence, was an ideal setting for aestheticism, “a sort of little fairy palace,” as Whistler described it, “—a thing on a fan—or on a blue plate.”149