“Life and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt: Ancient Egyptian Art from the Senusret Collection” is an exhibition about the power of ancient Egyptian objects to educate, engage, and inspire. The Georges Ricard Foundation gifted the Senusret Collection to the Michael C. Carlos Museum in 2018, with the understanding that the collection would be conserved and used to promote knowledge. In keeping with this trust, the exhibition highlights objects that have promoted technical and scholarly collaboration, faculty and student research, methods of analysis, provenance tracing, and past object history.

The collection is named after the workman’s village Hetep-Senusret, meaning “[King] Senusret is Satisfied.” The town functioned as part of the pyramid complex of Senusret II at a site now known as Lahun in Faiyum, Egypt.

A wealth of small finds uncovered in the village by its excavator, William Flinders Petrie, struck Georges Ricard as particularly refined. It followed that he saw in the name Senusret a simile for his goal to create a museum as a haven showcasing the refinement of ancient Egypt and the Mediterranean world.

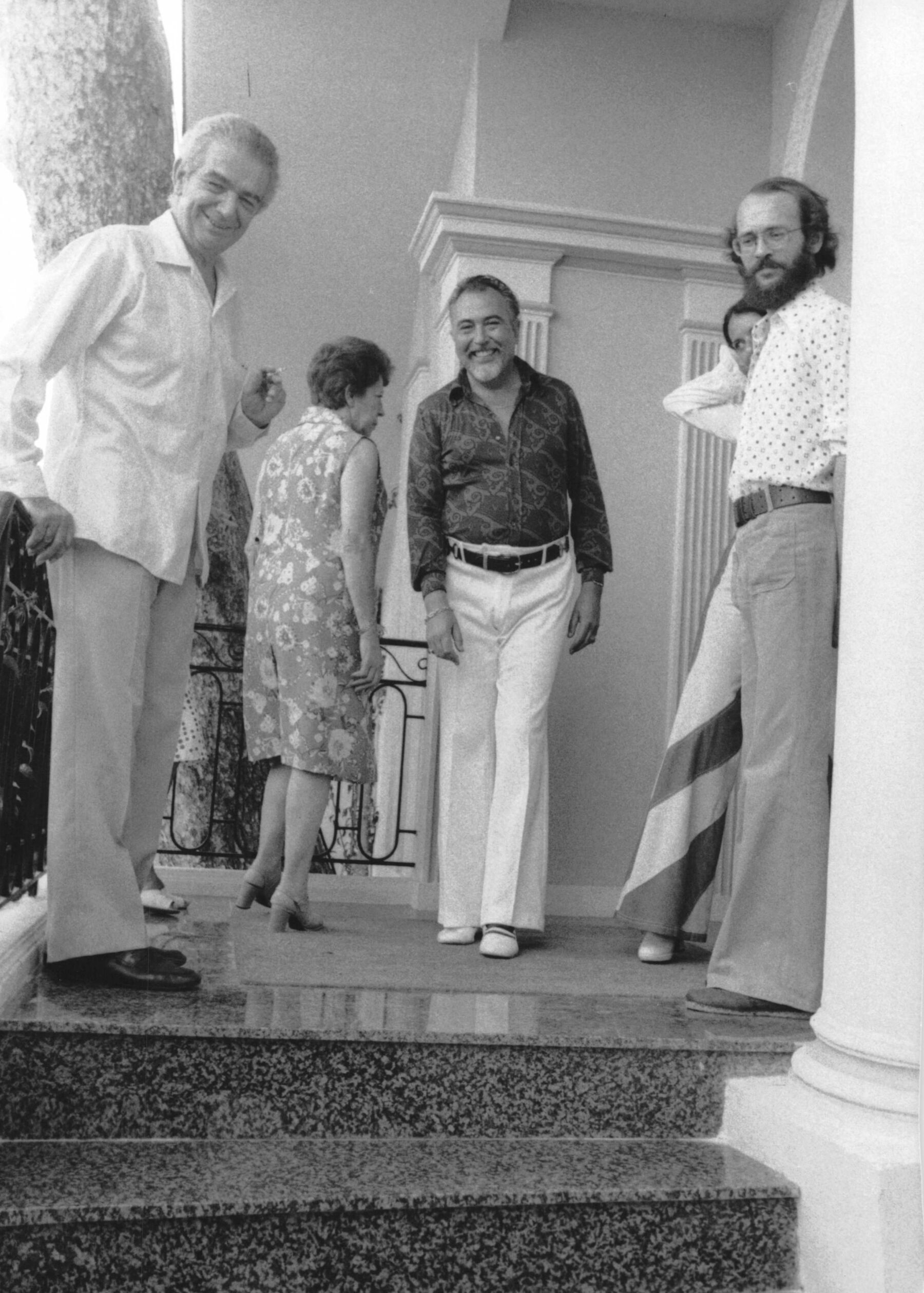

It all started in the 1960s when, after a successful career in industry, Georges returned to his earlier academic focus on art, developed a great interest in the ancient world, and began to assemble his collection—an eclectic mix that reflected the broad interests of its collector (Figure 1.1).1

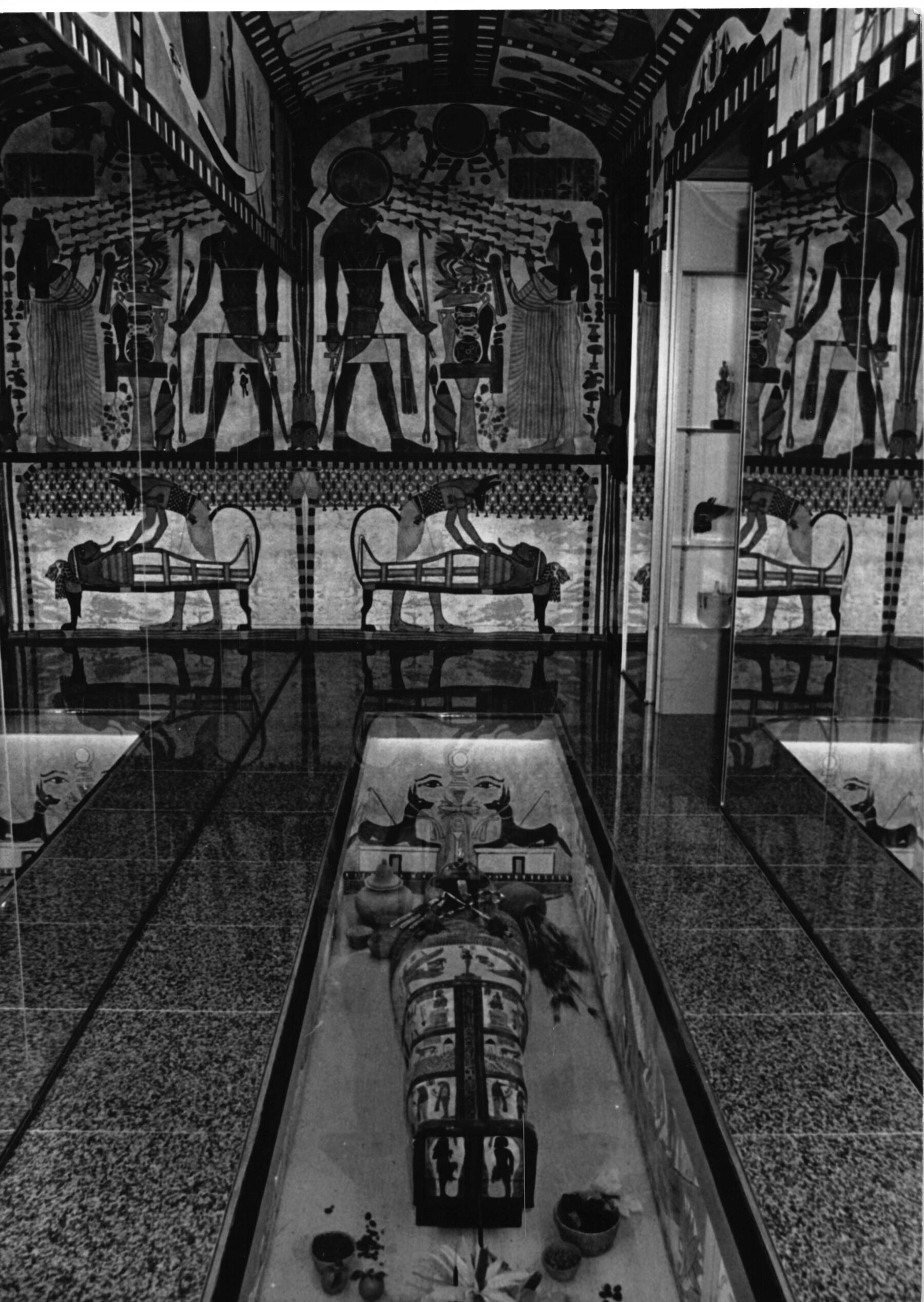

Objects included ancient pottery, glass, coins, metal figurines, jewelry, beads, amulets, shabtis, and masks. Eventually, the collection grew so large that Georges felt a moral obligation to share it with the public. As he formed the project of opening a museum in his new home country of Monaco, he endeavored to collect more purposefully to illustrate life (and the afterlife) in the ancient world. With approval by ministerial decree and government authorization, he formed the SAM Sanousrit corporation to acquire the only private villa in Monaco-Ville and create a space to display ancient art in a resolutely modern setting.2 He opened the Musée l’Egypte et le monde antique on June 5, 1975. Visitors entered the museum by walking over a glass gangway with a replica of an Egyptian tomb below (Figure 1.2).

The walls were painted with scenes from ancient Egyptian tomb chapels by the artist Jacques Bonnery. Lacquered ceilings, mirrored walls, and polished red granite floors reminiscent of Aswan reflected the ancient objects presented in polished aluminum and glass vitrines upholstered in silk. The museum was a hit with tourists, schools, and local citizens alike. Unfortunately, three years later, unsatisfactory climate/conservation conditions resulting from architectural design flaws compelled Georges to shut the museum’s doors.

Georges moved to California. He soon entered into negotiations with the art museum at the University of California, Santa Barbara, to serve as custodian for the collection, but plans were halted due to state budgetary cutbacks. So, in 1987, Georges founded the nonprofit public benefit corporation, the California Institute of World Archeology (CIWA), to apply California’s computer know-how to the service of the archeological community (“bringing Silicon Valley to the Valley of the Kings”). Projects included the development of a hieroglyph notation system and the establishment of a unified worldwide database of antiquities. Ricard’s goal was to foster academic research and help join object fragments. But with the rise of the World Wide Web, CIWA eventually focused on the pioneering development of a virtual museum based on the Senusret collection.

It took Georges and his son three years to catalog and photograph the collection so that the objects could be made available online through the Virtual Egyptian Museum (VEM) website. The VEM went online in 2003. The intent was to provide scholars, students, and those living far from cultural resources with a museum experience, and it allowed the public to continue to learn from the collection while a permanent home in a public museum was sought. A few years before his death, Georges Ricard transferred the Senusret Collection to a trust for the benefit of the CIWA, a 501©(3), which, after his death, was renamed the Georges Ricard Foundation.

In 2018, the Georges Ricard Foundation assembled a distinguished group of Egyptologists to find a new home for the Senusret Collection. Their criteria: a museum with quality conservation care and robust teaching and outreach programs. A number of US museums were considered. In the end, the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University was selected as the collection’s permanent home to serve as a resource for university faculty, students, schoolchildren, and the wider public.

The VEM website database, with its high-quality object photographs, was transferred to the Michael C. Carlos Museum (MCCM). While the VEM website temporarily remains accessible online, the information is static. The most up-to-date object descriptions and research can be found on the MCCM’s permanent collection website, including provenance information.

Since the arrival of the Senusret Collection, the Michael C. Carlos Museum has endeavored to follow the Georges Ricard Foundation’s mission that the objects contribute to knowledge. Over the last four years, our staff collaborated with conservators, Emory faculty, scientists, students, and national and international scholars. Their work has culminated in this exceptional exhibit of 165 artifacts, carefully restored to captivate and educate its visitors about life and the afterlife in ancient Egypt as well as issues of cultural patrimony, methods of analysis, provenance research, technical study, and digital investigation.

Ending with a quotation from Georges’s son, Yann Ricard, “we never intended or imagined the Senusret Collection would leave California, but once we met the Carlos Museum staff, the unthinkable turned into the compelling. Although we didn’t want to part with the collection, we soon became convinced that entrusting it to the Carlos was a golden opportunity to realize all the hopes and dreams Georges had for it since its arrival in the United States more than 30 years ago. Nowhere else could we find such a cohesive, dedicated, and creative team of consummate professionals on a mission not only to lovingly preserve our world’s cultural heritage but also to use the collection to ignite imaginations, convey meaning, elicit emotion, and inspire reflection.”