Modern science is fortunate that such a large segment of the population of the ancient city of Akhmim still exists today in the form of mummies brought from its cemeteries at the end of the 19th century. Taosiris and Padibastet are just two of the many mummies excavated there in the seasons of work following the discovery at the southern-end vast cemetery district of the particularly crowded Akhmimic burial zone called Al-Hawawish in 1884. So enormous was the haul of coffined bodies from the place that the Egyptian government of the time chose, after setting aside those it felt were the best, to sell off any mummies that it determined to be extraneous. In this way, the mummies of Taosiris and Padibastet were acquired by French owners before entering the Senusret Collection (Georges Ricard Foundation) years later. Director of Egyptian Antiquities Gaston Maspero gave Taosiris’s mummy and coffin to the magician and showman Marius Cazeneuve in 1884. Padibastet’s mummy and coffin entered a private collection in or near Lyon, France, in the mid-to-late 1880s or 1890. The mummies were CT scanned at Emory University Hospital on the evening of February 25, 2020. Research on the mummies has helped to clarify our perceptions of Ptolemaic period mummification, moving us beyond traditional literature, now a century old.1 Visual study of Taosiris and Padibastet resonates with findings made on other Akhmimic mummies autopsied by palaeopathologists in the 1970s.2

Taosiris

Taosiris is the earlier of the two mummies. She is datable to an early phase of the Ptolemaic period judging from stylistic features visible upon her brightly painted coffin. Like other containers manufactured at the time, ostensibly not long after the accession of Ptolemy II (282 BCE), the surface shows contrastive use of yellow and light blue pigments as background colors alongside major areas of red. The coffin shows a high standard of artistry. The figural detail is imaginative and very nicely rendered (for a detailed description of Taosiris’s coffin, see cat. no. 59). Another coffin comparable in its color scheme and stylistic features is the well-known coffin of the priest Nes-shou.3 Ostensibly, it belongs to the same phase.

Visual analysis of the body indicates that Taosiris was 35 years or slightly older at the time of death. Her living stature was 151–152 cm (59.5–59.8 in.). Her body exhibits no visible fractures or abnormalities. Osteopenia (low bone density), a condition not uncommon in the Akhmimic population of the Ptolemaic period, is noted in Taosiris but had not yet developed into age-associated osteoporosis as seen in other inhabitants of Akhmim, which could be quite severe.4 Evidence of osteoarthritis in her joint spaces is minimal.

Her well-preserved body was equipped with a suit of beautifully painted cartonnage trappings (Figure 4.1). The four-piece ensemble consists of a helmet mask, a combined chest and torso cover, a shin cover, and a foot cover known as a “boot”.

The chest and torso cover has a style more akin to that of Saqqara: The top compartment has an image of the winged solar beetle Khepri; the band below it contains a repetitive motif of the royal tutelary goddesses Wadjet (the cobra of Lower Egypt) and Nekhbet (the vulture of Upper Egypt) flanking seated gods. Squarish pieces of gold leaf adhered to the heads of the figures depicted on the trappings, some being the protective funerary deities, others being the solar disk, and a small figure of the mummy itself. The attachment of gold squares is seen in other cartonnage trappings associated with Akhmim, such as those associated with the mummy of the woman Pesed.5

These trappings were attached to a rectangular shroud of fine linen (32.5 cm wide × 115 cm long) draped upon the mummy from the upper chest to the feet after a thick deposit of dark resin had been brushed on from head to foot and allowed to dry completely. This was the standard treatment for all mummies of elite persons at Akhmim. Such shrouds are often faded, but some were originally dyed a vivid salmon-red at Akhmim and other Egyptian and Nubian sites.6

The shroud lay atop a dark layer of resin that extended from head to foot (Figure 4.2). While in a viscous condition, it had been brushed thickly onto the transverse wrappings forming the outer part of Taosiris’s mummy bundle. Because it is nearly black, this viscous resin is sometimes mistaken for bitumen (a tar of mineral origin) but is likely a botanical substance composed of diterpenic sap from nonconiferous species such as Pistacia and materials like beeswax and botanical oils (fats) like castor. It was allowed to dry thoroughly and harden before the shroud was added. It was evidently part of a ritual intended to sanctify the wrapped mummy before the final dressings were applied to it.

The immediate functional goal of Egyptian mummification was to remove organs and cleanse the body’s internal cavities to promote nearly complete desiccation of the body while preserving its external form. The arms of the mummy were each carefully wrapped and positioned in a distinctive way which earlier in Egyptian history had been associated with female royals. The left arm was bent at the elbow, and the left hand, clenched into a loose fist, was placed against the right humerus. The right arm drops down along the right side so that the forearm overlies the right wing of the pelvis, with the relaxed fingers of the right hand ending up on the medial aspect of the right thigh.7

In keeping with Late Period norms (as reflected in the writings of Herodotus), the embalmers removed the brain from Taosiris’s cranium, a procedure called excerebration, by introducing a narrow perforator-tool through the nasal passage and breaking through the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone. Viscous resin was injected into the empty brain case while the body lay on its back, forming a pool in the occipital cavity of the skull. The embalmers inserted plugs made of resin paste into each of Taosiris’s nostrils to seal and protect these openings. Around the same time, each of the ears was coated with resin preserving their forms intact. It is noteworthy that Taosiris’s eyes were left alone within the orbits and not removed; the same approach was taken with other Akhmimic mummies of the period.8

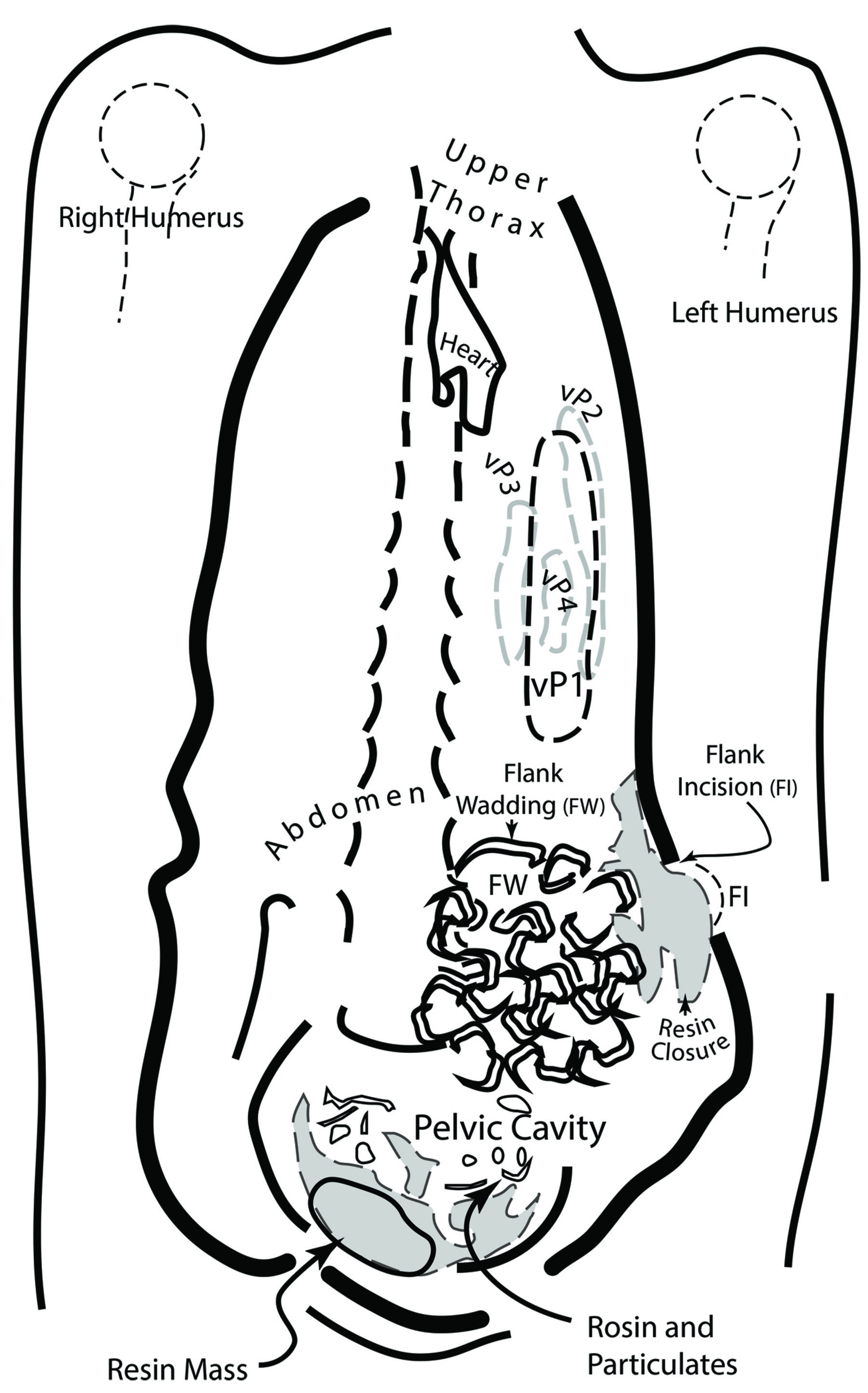

The thorax and abdomen were fully eviscerated by way of an incision made above the left iliac crest to permit desiccation to proceed, probably by means of natron packets. All internal organs were removed through this flank incision with the exception of the heart, and its retention in place is entirely part of standard practice. The diaphragm muscle is also intact and in normal position. The body cavities were presumably cleansed following the removal of the natron packets, and the embalmers separately mummified the extracted viscera and prepared four cloth-wrapped visceral packets with organ residues inside, which were reintroduced to the body. They cluster in a group within the left side of the abdominal cavity. In addition to the four visceral packets, Taosiris’s mummy was equipped with a formed resin mass within her pelvic cavity. It is nestled amidst rosin and particulates. Viscous resin fills the thorax. Once all interior embalming work had been completed, a mass of linen wadding was inserted into the left lower abdomen to close up the flank incision (Figure 4.3).

While the embalmers wrapped the torso with elaborate layers of wrapping, they inserted several objects best described as cords (made of linen). One was placed within the bandages on the front of each shin, while a third, longer cord stretched within the bandage layers between the ankle and clavicle. Those on the shins have been found on other mummies and have come to be known as shin cords. The longitudinal “body cord” is only known on Taosiris.

Padibastet

Padibastet, the name today used to identify the male mummy, derives from auction records intended to associate the mummy with a king who reigned in the 9th century BCE and has no evidentiary basis in the texts on the accompanying coffin. This mummy is not in the exhibition.

Although it has been badly abraded through the years, the coffin is identifiable as Akhmimic style dating to the middle to late 3rd century BCE, several decades after the mummy of Taosiris. This finding is based on features like the increased number of decorative bands in its falcon-headed collar design, which have become narrower and more schematic compared to the bands painted on the coffin of Taosiris.

Processually speaking, his mummy displays broad similarities to Taosiris’s mummy, which is expectable given that he was a member, like her, of the citizenry of ancient Akhmim. The outermost layers of wrapping have suffered extensive damage through the centuries, and the cartonnage trappings are wholly missing. The shroud is gone, leaving the outer resin encapsulation layer exposed. This ritual resin coating has been ripped off the upper chest but still adheres to the head, abdomen, and legs. Given the comparatively high standard of bandaging and other funerary preparation, Padibastet would likely have been equipped with cartonnage trappings similar to those associated with Taosiris (Figure 4.4).

Padibastet’s head tilts backward. As with Taosiris, excerebration proceeded nasally, and the brain residues were extracted through a perforation made in the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone. Again, embalmers poured viscous resin into the occiput following the removal of the brain. The depth of the resin pool is 69 mm, double that seen in Taosiris. Resin flowed down the esophagus. Cloth was inserted into the mouth, and Padibastet’s nostrils were plugged with linen inserts. Tissues of the eyes remain within each orbit, and sufficient care was taken with the treatment of the head so that the preservation of the soft tissues of the face was excellent, including the eyelids and lower lip.

Visual analysis of the body indicates that Padibastet was between 55 and 65 years old at the time of death. His living stature was 168.6–170.0 cm (66.4–66.9 in.). The severe attrition of the teeth and loss of molars, and abscess formation in the maxilla support the finding that Padibastet was a relatively old individual. The impression of old age is borne out by the evidence of degenerative bone disease in his hip joints. Furthermore, subchondral cyst formation within his lower extremities is fairly extensive.

Padibastet’s arms are uncrossed; each upper arm falls at the side, and the forearm slightly bends at the elbow to direct the forearms diagonally upon each thigh. The fingers of each hand are relaxed on the center and medial facet of the thigh. Uncrossed arm positioning is relatively unusual among adults at Akhmim in the Ptolemaic period.9

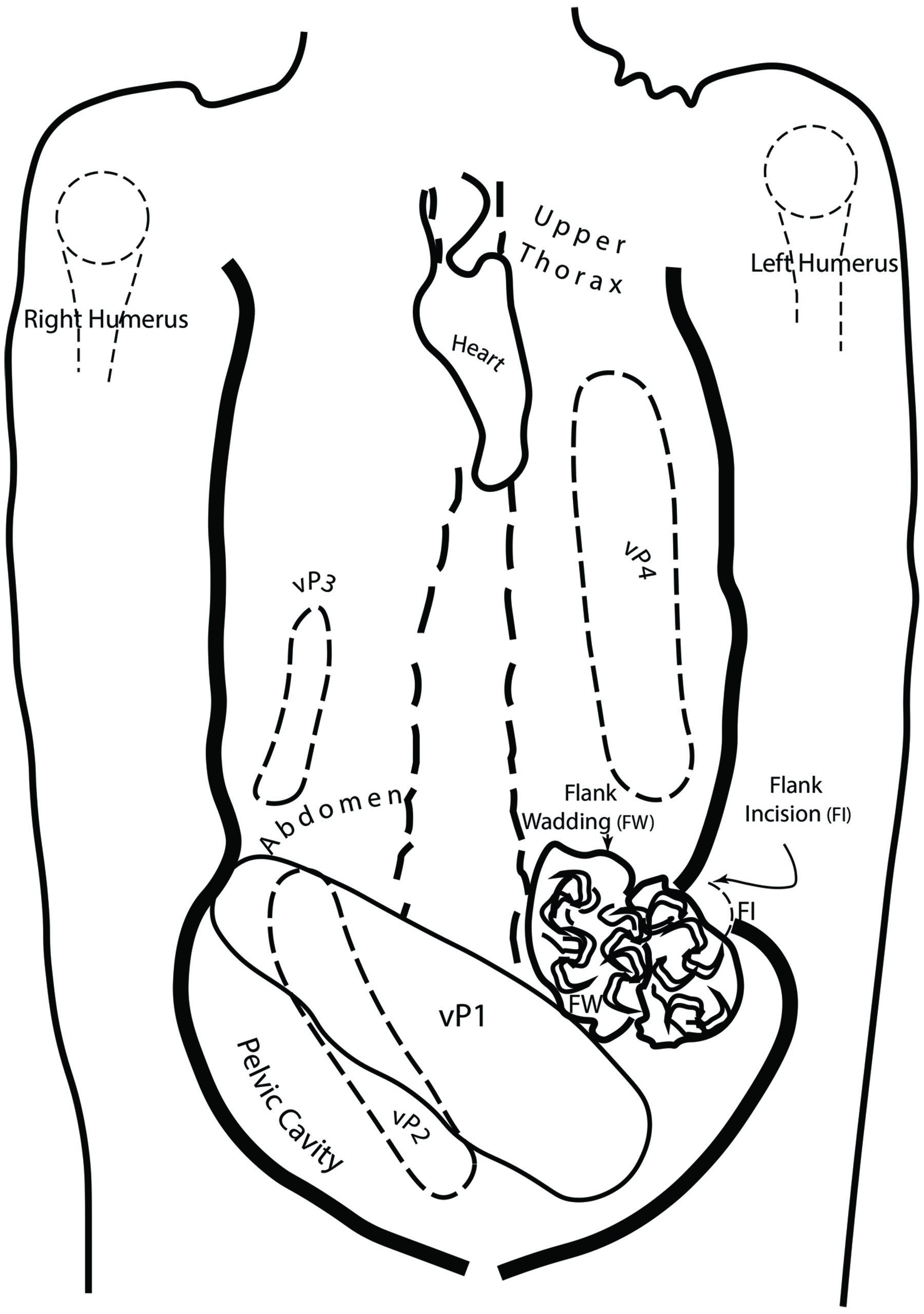

Evisceration was performed through an incision above the left iliac crest. As with Taosiris, the heart was deliberately avoided and remains attached. The distribution of the four visceral packets differs greatly from what was noted with Taosiris, whose packets were nestled together on the left side of the abdomen. In Padibastet’s case, two packets are placed diagonally on the right side of the pelvic cavity (fig. 9 [Padibastet embalming features thorax-abdomen-pelvis. Drawing by Jonathan Elias]). The third and fourth packets are located on either side of the vertebral column. One of the two “pelvic” packets is large (223 mm long) compared to its companion (179 mm) and is the largest of the four. All of the packets are submerged within the resin. The specific content of these packets cannot be determined based on the scans. Still, one Akhmimic example of Ptolemaic date contained elements of more than one organ, intestinal and spleen tissue.10

The amount of resin retained within Padibastet’s body cavities exceeds what was found in Taosiris. More had likely been poured into his body to begin with. Two linen wadding elements were inserted into the evisceration incision to seal the body prior to wrapping, as commonly seen in Ptolemaic period mummies at Akhmim .11 The addition of linen through the incisional defect to lodge in the left side of the abdomen is a feature regularly encountered in Ptolemaic mummies.12 The mummy’s legs have been wrapped voluminously in seven horizons of heavily pasted bandages. Such fulsome wrapping suggests that Padibastet was a member of an elite stratum, which the roughly handled exterior condition of his coffin and mummy somewhat obscured.

A bilobal feature below the pubic symphysis indicates that Padibastet’s penis has been anatomically preserved.13 Penis and scrotum are clearly indicated. They have been wrapped up in spiral bandaging in the void between the thighs. This practice is in keeping with common procedures for male mummies from Akhmim.14 The treatment of Padibastet’s genitalia is even more elaborate and involves the addition of an extensive oblong cushion of textile with granular fill placed above (in front of) the genitals. It is plausible to suggest that this sheathing relates to the special reverence with which Padibastet was held in the broader context of cult practices associated with the fertility god Min.

A textile roll has been placed behind the left arm. It is an unusual feature and was presumably added into the mummy bundle as part of the magical system intended to ensure protection and rejuvenation of the physical body. The left side of the body between the body wall and the arm is sometimes the focus for the placement of elements belonging to the magical tool kit, including waxen disks and funerary papyri inscribed with spells from the Book of the Dead.15 Padibastet’s textile roll may have been intended to function as a cloth amulet.

Padibastet’s upper arms exhibited linear markings of uncertain significance. There may have been traces of folds in the overriding bandages, but there is also a possibility that they had been drawn onto the arms to mark spots where special attention was warranted. Evidence from other Akhmimic mummies of the Ptolemaic period indicates that narrow bands (ribbons) were sometimes tied around the upper arms to perform some ritual or other funerary function.16

-

Smith, Grafton Elliot and Warren R. Dawson. 1924. Egyptian Mummies. London: George Allen & Unwin.. ↩︎

-

Cockburn, Aidan, Robin A. Barraco, Theodore A. Reyman, and William H. Peck. 1975. “Autopsy of an Egyptian Mummy.” Science 187 (March): 1155–1160.. ↩︎

-

Yverdon-les-Bains Switzerland Musée du Château MY 3775; Küffer, Alexandra and Renate Siegmann, eds. 2007. Unter dem Schutz der Himmelsgöttin: Ägyptische Särge, Mumien, und Masken in der Schweiz. Zurich: Chronos. ↩︎

-

Raven, Maarten, and Wybren K. Taconis. 2005. Egyptian Mummies: Radiological Atlas of the Collections of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden. Papers on Archaeology of the Leiden Museum of Antiquities 1. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols.. For osteopenia, see Harris, Mervyn. 2016. “An investigation into the evidence of age-related osteoporosis in three Egyptian mummies.” In Mummies, Magic and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Multidisciplinary Essays for Rosalie David, edited by Campbell Price, Roger Forshaw, Andrew Chamberlain, and Paul Nicholson, 305–316. Manchester: Manchester University Press.. ↩︎

-

Westminster College no. 48; Leveque, Mimi, Jonathan Elias, and Jessica van Dam. 2022. The Mummy and Coffin of Pesed. Waltham, MA: Archaea Technica Art Conservation Services.. ↩︎

-

Smith, Grafton Elliot and Warren R. Dawson. 1924. Egyptian Mummies. London: George Allen & Unwin.; For salmon-red, see Leveque, Mimi, Jonathan Elias, and Jessica van Dam. 2022. The Mummy and Coffin of Pesed. Waltham, MA: Archaea Technica Art Conservation Services.. ↩︎

-

Elias, Jonathan, Carter Lupton, and Alexandra Klales. 2014. “Assessment of Arm Arrangements of Egyptian Mummies in Light of Recent CT Studies.” Yearbook of Mummy Studies 2: 49–62.. ↩︎

-

Raven, Maarten, and Wybren K. Taconis. 2005. Egyptian Mummies: Radiological Atlas of the Collections of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden. Papers on Archaeology of the Leiden Museum of Antiquities 1. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols.. ↩︎

-

Elias, Jonathan, Carter Lupton, and Alexandra Klales. 2014. “Assessment of Arm Arrangements of Egyptian Mummies in Light of Recent CT Studies.” Yearbook of Mummy Studies 2: 49–62.. ↩︎

-

Cockburn, Aidan, Robin A. Barraco, Theodore A. Reyman, and William H. Peck. 1975. “Autopsy of an Egyptian Mummy.” Science 187 (March): 1155–1160.. ↩︎

-

Loynes, Robert. 2015. Prepared for Eternity: A Study of Human Embalming Techniques in Ancient Egypt using computerized tomography scans of mummies. Archaeopress Egyptology 9. Oxford, UK: Archaeopress.. ↩︎

-

Raven, Maarten, and Wybren K. Taconis. 2005. Egyptian Mummies: Radiological Atlas of the Collections of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden. Papers on Archaeology of the Leiden Museum of Antiquities 1. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols.. ↩︎

-

Cf. Raven, Maarten, and Wybren K. Taconis. 2005. Egyptian Mummies: Radiological Atlas of the Collections of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden. Papers on Archaeology of the Leiden Museum of Antiquities 1. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols.. ↩︎

-

Brier, Bob, N. Vinh Phuong, Michael Schuster, Howard Mayforth, and Emily Johnson Chapin. 2018. “The Mummy of Ankhefenmut: A Scientific Investigation.” In The Mystery of the Albany Mummies, edited by Peter Lacovara and Sue d’Auria, 79–93. Albany, NY: State University of New York.. ↩︎

-

For waxen disks, see Leveque, Mimi, Jonathan Elias, and Jessica van Dam. 2022. The Mummy and Coffin of Pesed. Waltham, MA: Archaea Technica Art Conservation Services.. For funerary papyri, see Anđelković, Branislav, and Jonathan P. Elias. 2021. “CT Scan of Nesmin from Akhmim: New Data on the Belgrade Mummy.” Issues in Ethnology and Anthropology, 16, no. 3: 761–794. https://doi.org/10.21301/eap.v16i3.7. ↩︎

-

Elias, Jonathan P. and Tamás Mekis. 2020. “Prophet-registrars at Akhmim.” MDAIK 76: 83–11.. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Anđelković and Elias 2021

- Anđelković, Branislav, and Jonathan P. Elias. 2021. “CT Scan of Nesmin from Akhmim: New Data on the Belgrade Mummy.” Issues in Ethnology and Anthropology, 16, no. 3: 761–794. https://doi.org/10.21301/eap.v16i3.7

- Brier et al. 2018

- Brier, Bob, N. Vinh Phuong, Michael Schuster, Howard Mayforth, and Emily Johnson Chapin. 2018. “The Mummy of Ankhefenmut: A Scientific Investigation.” In The Mystery of the Albany Mummies, edited by Peter Lacovara and Sue d’Auria, 79–93. Albany, NY: State University of New York.

- Cockburn et al. 1975

- Cockburn, Aidan, Robin A. Barraco, Theodore A. Reyman, and William H. Peck. 1975. “Autopsy of an Egyptian Mummy.” Science 187 (March): 1155–1160.

- Elias, Lupton, and Klales 2014

- Elias, Jonathan, Carter Lupton, and Alexandra Klales. 2014. “Assessment of Arm Arrangements of Egyptian Mummies in Light of Recent CT Studies.” Yearbook of Mummy Studies 2: 49–62.

- Elias & Mekis 2020

- Elias, Jonathan P. and Tamás Mekis. 2020. “Prophet-registrars at Akhmim.” MDAIK 76: 83–11.

- Harris 2016

- Harris, Mervyn. 2016. “An investigation into the evidence of age-related osteoporosis in three Egyptian mummies.” In Mummies, Magic and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Multidisciplinary Essays for Rosalie David, edited by Campbell Price, Roger Forshaw, Andrew Chamberlain, and Paul Nicholson, 305–316. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Küffer and Siegmann 2007

- Küffer, Alexandra and Renate Siegmann, eds. 2007. Unter dem Schutz der Himmelsgöttin: Ägyptische Särge, Mumien, und Masken in der Schweiz. Zurich: Chronos.

- Leveque et al. 2022

- Leveque, Mimi, Jonathan Elias, and Jessica van Dam. 2022. The Mummy and Coffin of Pesed. Waltham, MA: Archaea Technica Art Conservation Services.

- Leveque et al. 2022

- Leveque, Mimi, Jonathan Elias, and Jessica van Dam. 2022. The Mummy and Coffin of Pesed. Waltham, MA: Archaea Technica Art Conservation Services.

- Loynes 2015

- Loynes, Robert. 2015. Prepared for Eternity: A Study of Human Embalming Techniques in Ancient Egypt using computerized tomography scans of mummies. Archaeopress Egyptology 9. Oxford, UK: Archaeopress.

- Raven and Taconis 2005

- Raven, Maarten, and Wybren K. Taconis. 2005. Egyptian Mummies: Radiological Atlas of the Collections of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden. Papers on Archaeology of the Leiden Museum of Antiquities 1. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols.

- Smith and Dawson 1924

- Smith, Grafton Elliot and Warren R. Dawson. 1924. Egyptian Mummies. London: George Allen & Unwin.