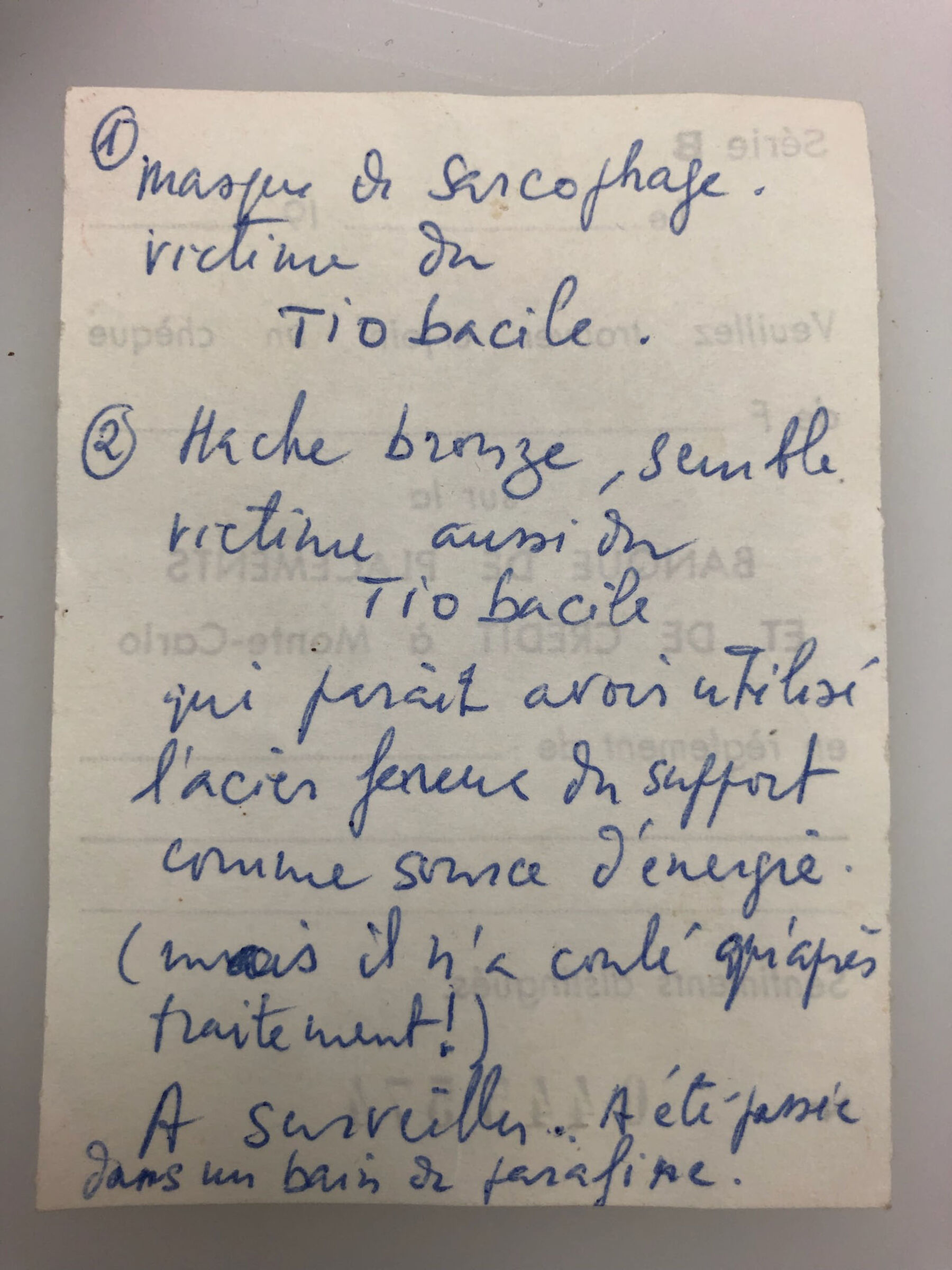

Collected objects often have long and complicated histories of care that impact strategies for their preservation. Like more contemporary interventions, past efforts to repair and restore objects aimed to stabilize fragile structures and improve their appearances. Records of these treatments rarely remain with the objects. A note written in French on a small piece of paper found with the Ricard collection bronzes indicates that an object was bathed in wax and should be monitored (Figure 5.1).

It is the only description of past treatment, and it is unclear to which object the note refers. Without documentation, contemporary conservators must infer information about past conditions and prior repairs from examination, materials analysis, and experience.

Some repair materials are recognizable and may be associated with a particular timeline. For example, shellac has a characteristic dark orange-brown color and often displays orange fluorescence when viewed under ultraviolet illumination. Cellulose nitrate was widely used as an adhesive from the late 19th century until its tendency to yellow and embrittle was understood as problematic in the 1980s. Similar to fashion, modes of intervention gain popularity in certain places and moments. The extensive reconstructions of archaeological or Medieval sculptures that had been common since the 17th century were frequently removed in the 1980s and 1990s in favor of a more minimalist approach. Interventions reflect the available resources and prevailing influences that motivate repair decisions. Past efforts were generally well-intentioned and informed by current knowledge of materials, deterioration processes, and preservation methods. Materials and methods for repair continually evolve as new supplies become available and new technologies are developed.

The materials used in prior repairs and the extent to which they have been applied may differ significantly from 21st-century conservation practices guided by codes of ethics through professional organizations such as the American Institute for Conservation and parallel entities in other countries. These guidelines for practice underscore the reversibility of repairs and legibility of the original object, dictating the selection of conservation materials and how treatments are executed. Structural interventions address the physical integrity of the object, while aesthetic repairs focus on appearance and are inherently subjective and relative.

Contemporary conservation recognizes that objects have many values, such as artistic, historical, monetary, documentary, cultural, sentimental, and many perspectives for assessing value, such as teaching, investment, display, evidentiary. When making decisions about an object’s care, these factors must be balanced with its physical needs, history of repair, immediate use, and future possibilities for interpretation, valuation, and use. A broken object might be stored as associated fragments but repaired when needed for display. New research might reveal that an old restoration is incorrect, warranting that it be documented and removed.

Past interventions can provide important evidence, and old repairs can be part of the object’s present identity. The wood, stone, or plastic bases secured to shabtis, bronze figurines, and amulets to make them stand upright for display often carry labels that point to the objects’ history of sale or collection. Often these historic bases are retained as evidence of the object’s history. Most beadwork has been restrung since the organic fiber cord rarely survives. This restringing often presents a modern aesthetic and interpretation. Probably restrung in the early 20th century, the scarab collar marries beads and amulets from different ancient contexts. Unstringing the fabrication would result in a pile of beads that neither represents the ancient object nor reveals historical tastes. The reconstructed object may become historically significant, as is the necklace (cat. no. 16) comprising ancient scarabs and a modern gold link chain belonging to the Victorian socialite Lady Meux, whose famous portraits were painted by James Whistler. In these cases, the historic construct is the object and must be preserved.

Treatment of these historic constructs focused on stabilizing their present structures and improving their current appearances. The faience bead net (cat. 97) was restrung with teal blue cotton thread and adhered with what appeared to be shellac to a burlap-covered plastic sheet, perhaps sometime in the mid-20th century. The brittle brown adhesive was released from the weak burlap and was partially reduced from the back of the beads with solvents. Missing round beads were replaced with embroidery thread tied from the back to reestablish the diamond pattern. Broken and missing long beads were replicated with toned paper wrapped around plastic tubing, cut to length, and inserted into the net with embroidery thread (Figure 5.2).

These additions stabilize and complete the object but are easily distinguished and can be removed without harm. A padded, fabric-covered board made from archival materials provides support for the bead net during handling and on display.

Sometimes old repairs cannot be undone. It may be impossible to remove the added materials due to their chemical composition, interaction with the ancient substrate, and/ or change over time. As restoration adhesives and coatings degrade, they often become insoluble, discolored, and brittle. These added materials may be extensively applied or absorbed and bound into the original materials. Removal could cause damage to the original object or require the use of toxic chemicals that are unsafe for conservators and the environment. These old repairs have thus become an intrinsic part of the object’s present state.

The large stone storage vessel (cat. no. 26) comprises five fragments that have been previously joined. Dating to the Late Period, this vessel was carved from banded travertine, often called “Egyptian alabaster.” The vessel has a wide, flat rim, two unperforated lug handles, and a rounded base. No evidence of applied or incised surface decoration remains. The five fragments were previously joined with an adhesive that was bulked to fill wider gaps and reinforced with thick mortar on the vessel's interior. Abrasions along the joins likely resulted from the filing or sanding of these repair materials. These restoration materials were discolored and/ or cracked with age (Figure 5.3).

While removing all traces of prior intervention and applying new materials may be desirable, the bulked adhesive and mortar are insoluble and intractable, making their complete removal unsafe for the object and unrealistically time-consuming.

The unsightly old repairs needed to be addressed in preparation for display. The discolored adhesive and cracked fill were reduced mechanically from within the joins using a scalpel and working slowly under magnification. By excavating the old repair materials from within the joins, a shallow recess was cleared to receive a layer of a synthetic, pigmented wax-resin mixture that matches the translucence and color of the stone. A thin barrier layer of adhesive applied to the receiving surface isolates the new fill and will facilitate its future removal. The wax-resin mixture was applied molten and then smoothed with a heated spatula. These compensations fill only the areas of loss and do not extend onto the vessel surface. The color of the wax-resin fill was adjusted with acrylic paints to simulate the banded patterning of the travertine. Although long-term stable, the materials used in this intervention can be removed without causing damage to the ancient stone.

Past restoration may hide damage by repainting, often extending beyond the perimeter of the loss and over original surfaces to make an object appear whole or pristine. Several decorated coffin lid fragments were restored by repainting, including the head and collar portion of what was a whole coffin dating to the Saite period (cat. no. 70). The coffin was constructed from many rough-hewn boards of Ficus sycamorous dowelled together with denser woods. Layers of mud, linen, priming, and paint were applied to model the form and create the decorated surface. At an unknown date, the head and collar were sawn off from the rest of the coffin, perhaps for ease of transportation or to match collecting tastes. At a later moment in the object’s continuing history, approximately three-quarters of the wig and half of the face were filled and overpainted to hide significant damage and losses. This overpaint was obvious to the unaided eye. It is a different hue of blue, and it is shinier than the surrounding matte, rough ancient paint colored by Egyptian blue pigment. To visually integrate the restoration with the original surface, the overpaint extends over undamaged ancient areas, as is revealed in visible-induced infrared luminescence (VIL) images in which the bright luminescence of Egyptian blue is seen in overpainted areas (Figure 5.4).

One of the initial goals for treating this coffin lid fragment was to reduce or remove as much of the overpaint as possible. Although some of the many layers of overpaint were soluble, they had absorbed into the porous, ancient paint layer. They were, therefore, impossible to remove without also removing or damaging the original material. The disfiguring and distracting appearance of the old restoration was minimized by applying an aesthetically cohesive material to cover the overpaint. A lightweight, unsized paper with long fibers was chosen because of its matte appearance and ability to conform to surfaces. This paper was toned with acrylic paints before applying it to the object. The toned paper was adhered to the object with a weak adhesive, holding it securely in place but allowing it to be gently removed in the future. This method of compensating for the restored surface preserves past intervention evidence while presenting a visually coherent object. Because the toned paper can be readily removed, this treatment can be reversed without causing damage to the original object.

These new treatments also become part of the objects’ histories, reflecting current resources, methods, and attitudes. Observations about construction and condition are thoroughly noted, along with imaging and analysis data. Decision rationales, specific interventions, and conservation materials are also documented. This treatment documentation is added to the object records in the Carlos Museum’s collection information database. These most recent treatments are another step in the lifetime of the objects. Conservators undertake these interventions mindful of the possibility for future investigation or retreatment, humbled by the knowledge that these ancient objects will be cared for by future generations.