From the late Old Kingdom through to the late Middle Kingdom, three-dimensional wooden scenes of daily life, and tomb models, were crafted and deposited in tombs and burial shafts across Egypt. The most numerous of these models were boats. The Senusret model solar boat (Catalog 80) stands out among this miniaturized fleet (Figure 6.1).

With a dozen figures crowded in, working now-perished rigging framed by unusual finials, it is apparent that not all the elements of this boat belong together on one model. This model is a combination of at least three ancient vessels. The modern addition of components to tomb models and combining several to make one artwork was not uncommon when the models were prepared for sale or display in museums. The phenomenon is, however, rarely discussed despite the ancient use of the tomb models and the more modern reception and interaction with them. As a case study, the Senusret model solar boat provides a lens to view the life—the creation and function of tomb models in burials—and the afterlife—the modifications and sale—of such objects with complex histories.

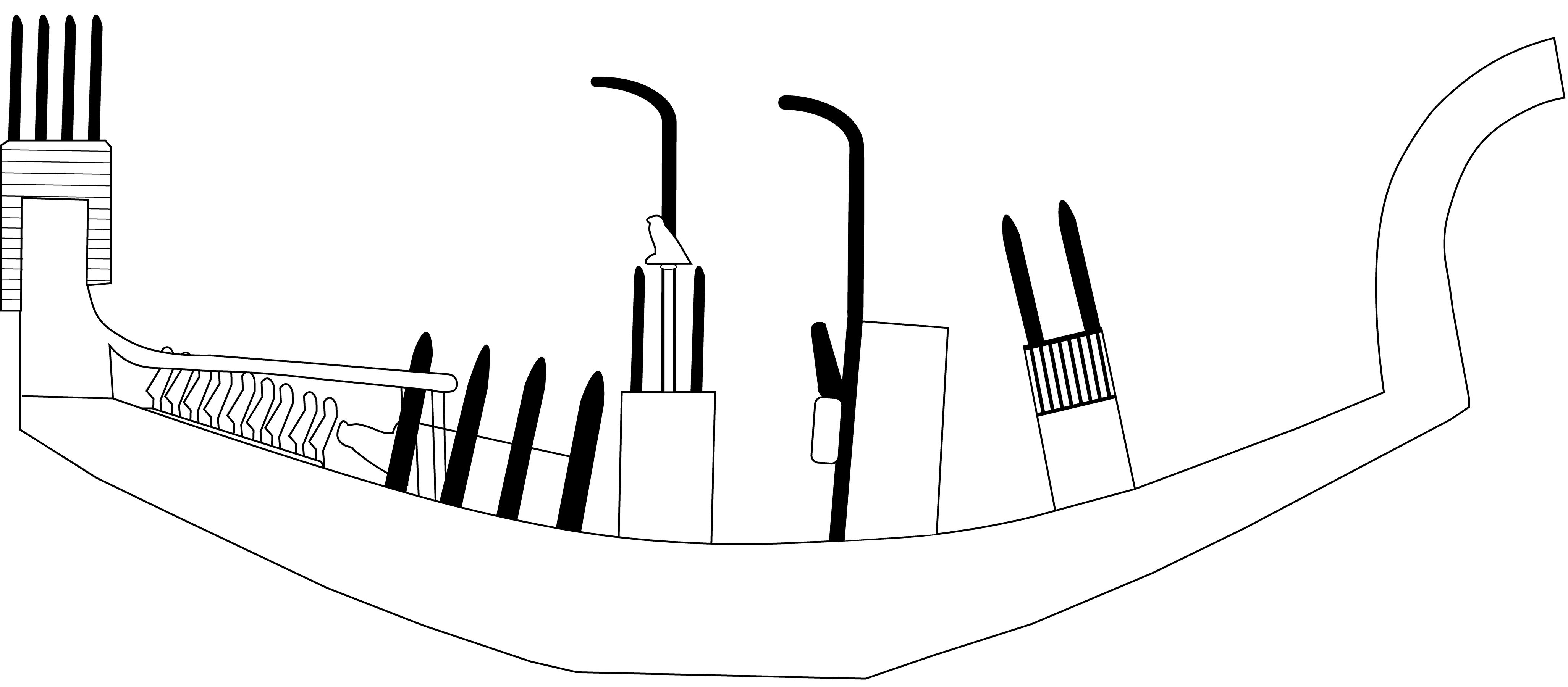

When excavating the Middle Kingdom cemetery of Beni Hasan, John Garstang determined that typical burial models included two boats: one sailing, one rowing.1 In addition to the sailing and rowing vessels, burials could have fishing, kitchen, or funerary boat models, with perhaps the least common being solar boats. Unlike other boat models, solar boats have no human figures aboard nor a means of propulsion; instead, they carry unique boat furniture (Figure 6.2).

For example, at the bow, there is a finial with a striped top or cover and two armrest-like railings extending out. Occasionally these railings are painted with a beaded pattern or holes, probably indicating the presence of a beaded cover that is now lost. Between these railings is a board mounted with several ma’at-feathers and a rectangular object with four black posts to either side with falcons on the end facing upward. Toward the center of the vessel is a cylinder with projecting stakes, one with a falcon on top, and a longer curved stake. In front of this is a rectangular box with a bow finial that forms the hieroglyphic shemes-sign, which means “to follow.” Just before the stern is a striped rectangular box with four black posts at each corner.2 The stern is upturned and is painted white and black.

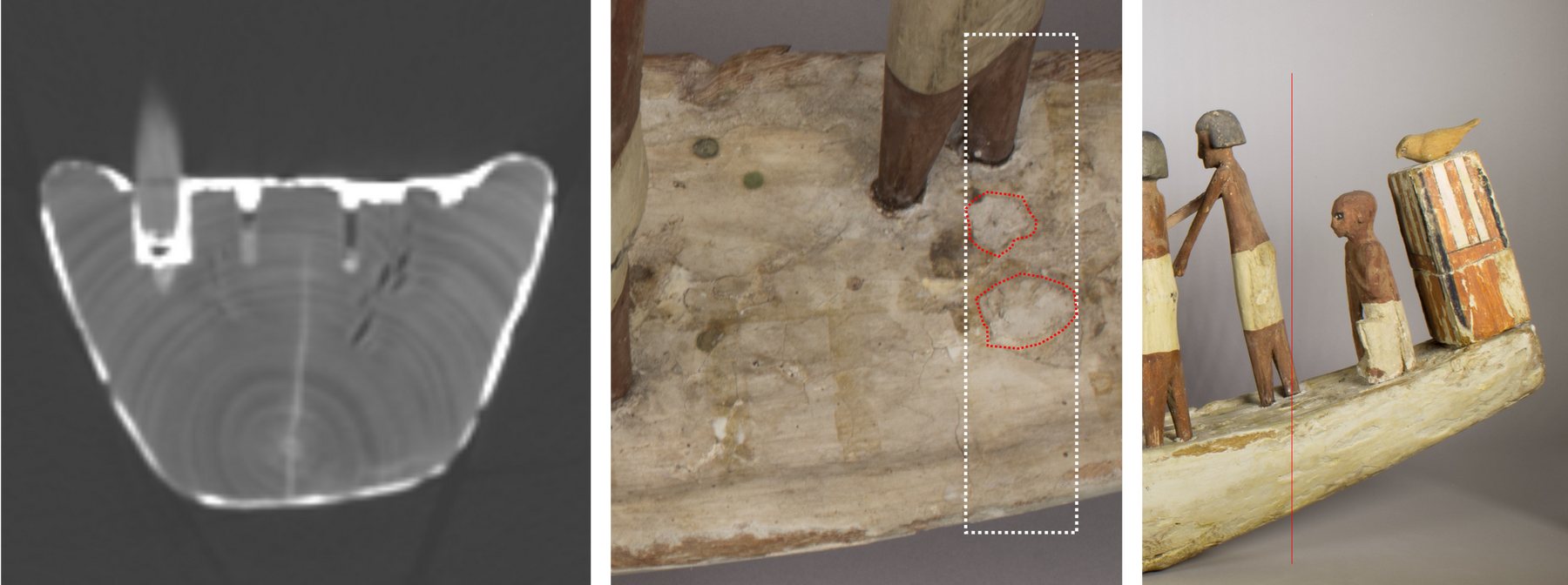

The Senusret solar boat is visually identifiable in part as a solar boat by the striped rectangular box, falcon, and bow finial with a striped cover. A CT scan of the boat demonstrated that the hull belonged to a solar boat with the presence of a multitude of ancient dowel holes that had been covered over by modern plaster (Figure 6.3).

Therefore, all the figures and the mast were added to the hull later. The question is, from what boat did they once belong? The same CT scan showed that the wooden figures have metal pins in every shoulder. This is not in keeping with ancient construction, where these arms would have been attached with wooden dowels.3 However, near these modern pins, the original dowel holes can be seen on all twelve figures, meaning they were ancient and came from other tomb models.

Standing wooden figures are found in a range of models, but they are most plentiful on sailing vessels. However, figures of this size and scale could not have all been from the same boat model, as they usually have no more than five standing upright figures (Figure 6.4).

These ten standing figures were likely from two sailing vessels, possibly from the same site, given their stylistic similarities. Some of the standing figures could have been on funerary boats, which depict the deceased on a funerary bier attended by mourners and priests. While these vessels rarely have a means of propulsion, during the reigns of Senwosret II and Senwosret III, funerary boats have sailors and a mast. These funerary boats have kneeling figures comparable with the two crouching men at the bow and stern, holding one arm across their chest in a gesture of adoration toward the deceased.4 Such a gesture is seen in figures that are kneeling near the image of the deceased either in a ritual role on a funerary boat or steering a boat that is either rowing or sailing. It is possible that the figures came from twelve different models; yet the similarities in size and construction indicate they came from a minimum of two model sailing boats, with one containing a wooden figure of the deceased, either seated or on a funerary boat as a mummiform figure.

While now part of one object, these three boats had different purposes in their original contexts. Sailing vessels tended to be found in a pair, with one rowing vessel journeying up the Nile and the other downstream. These paired vessels symbolized the journey to and from Abydos or Busiris, two major cult sites in the Middle Kingdom.5 The funerary vessels depicted the journey of the deceased to his burial site. Both model themes are also found in tomb wall paintings. They depict and make manifest the relationships with individuals and the activities taking place in the world of the living on behalf of the deceased. In contrast, solar boat models are without contemporary representations on tomb walls and without figures. The closest temporal, two-dimensional representation of model solar boats is on the pyramidion of Khendjer, a Dynasty 13 king. The pyramidion depicts the night and the day barks, bow to bow.6 The pyramidion provides a different context than private tomb paintings by placing the solar boat in the royal realm. This royal connection seems to suggest a relationship between solar boat models and other royal insignia found in private burials later in the Middle Kingdom.7 These objects are ritual in nature and focus on the transformation of the deceased into a divine ancestor. The solar boats with clear provenance have been securely dated to the reigns of Senwosret II and III, a period of innovation right at this point of transition in burial goods.8 Therefore, in this one artwork there are several purposes and functions competing with each other: the transformation of the deceased, the activities of the ancestor cult in the form of journeys to burial or to Abydos, and the making manifest the relationship between the deceased and the world of the living.

Such pastiche models are very common in museum collections around the world, yet rarely discussed. They can be the combination of multiple models with different purposes into one, like the Senusret solar boat, completely modern additions to an ancient model, just one ancient figure or piece of furniture added or placed in the wrong position, or anything in between. An archived letter between W. Flinders Petrie and the director of the Ipswich Museum, G. Maynard, published by Margaret Serpico, provides a window into the disbursement and modification of models from excavations:

I am happy to say that I find we have been able to repair a boat, granary and group so that they are better than many that we have distributed … all the boats and groups had to be packed in separate pieces and built up again in London, except those which were dispatched as they arrived packed from Egypt. 9

While it is unclear what the referenced repairs were, it is apparent that pieces of models were sent separately, and then were reconstructed for display.10 This disbursement method led to models with figures not in their original positions, elements added to other models, and models being split across museum collections.11 Thus, even with models from archaeological excavations, there is a strong possibility that they were intentionally, or somewhat unintentionally, modified. While it is far more likely that the Senusret solar boat was compiled by a dealer, who had no knowledge of its primary context and form, these letters show the demand for such models and the context into which the models were entering Europe and America. These wooden models demonstrate the great value placed on “complete” models for museum and private collections during the 19th and 20th centuries.12 The idea of completeness in the case of the Senusret solar boat, and the other recorded pastiche solar boats seems to rest on the inclusion of figures. None of these models closely mimicked other boats and the activities taking place on board, nor attempted to create a particular narrative. Rather, it seems for sale, the multitude of figures represented significant added value, at least in the minds of the individual(s) creating these essentially new art works.

The Senusret solar boat has had several lives and an eventful afterlife. It was once at least three model boats deposited in burials shafts in the Middle Kingdom in Egypt. The figures and mast on the boat stand for the two, if not more, sailing vessels—whether on a pilgrimage to Abydos or to take the deceased to burial. The hull, bow finial and cover, shrine, and falcon, come from a solar boat model, a short-lived three-dimensional innovation during the transition between two burial practices, part of the transformation of the deceased into an Osiris-like ancestor. In its more recent history, its afterlife, three or more boats come together to create a new work of the 19th or 20th century and reflects what the people involved in its creation thought an Egyptian model boat was thought to be, and what was valued: seemingly, in this case, the figures.

-

Garstang, J. 1907. Burial Customs of Ancient Egypt: As Illustrated by Tombs of the Middle Kingdom: A Report of Excavations Made in the Necropolis of Beni Hassan during 1902-3-4. London: Kegan Paul.. ↩︎

-

Reisner, G.A. 1913. Models of Ships and Boats. Catalogue Général des Antiquités Égyptiennes du Musée du Caire, nos. 4798–4976 and 5034–5200. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.. ↩︎

-

Lokma, N. 2001. “The Reconstruction of a Group of Wooden Models from the Tomb of Djehutinakht in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.” Bulletin of the American Research Center in Egypt 181, no. 1: 3–6.. ↩︎

-

Dominicus, B. 1994. Gesten und Gebärden in Darstellungen des Alten und Mittleren Reiches. Studien zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altägyptens 10. Heidelberg: Heidelberger Orientverlag.. ↩︎

-

Garstang, J. 1907. Burial Customs of Ancient Egypt: As Illustrated by Tombs of the Middle Kingdom: A Report of Excavations Made in the Necropolis of Beni Hassan during 1902-3-4. London: Kegan Paul.; Tooley, Angela M.J. 1989. “Middle Kingdom Burial Customs. A Study of Wooden Models and Related Material.” Ph.D. diss., University of Liverpool.; Freed, R.E., and D.M. Doxey. 2009. “The Djehutynakhts’ Models.” In The Secrets of Tomb 10A: Egypt 2000 BC, edited by Rita E Freed, Lawrence M. Berman, Denise M. Doxey, and Nicholas S. Picardo, 151–177. Boston: MFA Publications.. ↩︎

-

Jéquier, G. 1933. Deux Pyramides Du Moyen Empire. Cairo: l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Oritentale.; Thomas, E. 1956. “Solar Barks Prow to Prow.” JEA 42: 65–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/3855125. ↩︎

-

Smith, Mark. 2008. “Osiris and the Deceased.” UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, edited by Jacco Dielman and Willeke Wendrich. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/29r70244; Grajetzki, Wolfram. 2014. Tomb Treasures of the Late Middle Kingdom: The Archaeology of Female Burials. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.; Nyord, Rune. 2014. “Permeable Containers: Body and Cosmos in Middle Kingdom Coffins.” In Body, Cosmos and Eternity, edited by R. Sousa, 29-44. Oxford: Archaeopress.. ↩︎

-

Meyer, Marleen de. 2016. “An Isolated Middle Kingdom Tomb at Dayr Al-Barsha.” In The World of Middle Kingdom Egypt (2000-1550 BC): Contributions on Archaeology, Art, Religion, and Written Sources, edited by Gianluca Miniaci and Wolfram Grajetzki, 85–116. Middle Kingdom Studies 2. London: Golden House Publications.; Barker, Georgia. 2022. Preparing for Eternity: Funerary Models and Wall Scenes from the Egyptian Old and Middle Kingdoms. BAR International Series 3070. Oxford: BAR Publishing.. ↩︎

-

Letter from Petrie to Maynard in October 1921, as quoted by Serpico, M. 2008. “Sedment.” In Unseen Images: Archive Photographs in the Petrie Museum, edited by Janet Picton and Ivor Pridden, 99–184. London: Golden House Publications.. ↩︎

-

Serpico, M. 2008. “Sedment.” In Unseen Images: Archive Photographs in the Petrie Museum, edited by Janet Picton and Ivor Pridden, 99–184. London: Golden House Publications.. ↩︎

-

Serpico, M. 2008. “Sedment.” In Unseen Images: Archive Photographs in the Petrie Museum, edited by Janet Picton and Ivor Pridden, 99–184. London: Golden House Publications.. ↩︎

-

Barker, Georgia. 2022. Preparing for Eternity: Funerary Models and Wall Scenes from the Egyptian Old and Middle Kingdoms. BAR International Series 3070. Oxford: BAR Publishing.. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Barker 2022

- Barker, Georgia. 2022. Preparing for Eternity: Funerary Models and Wall Scenes from the Egyptian Old and Middle Kingdoms. BAR International Series 3070. Oxford: BAR Publishing.

- Dominicus 1994

- Dominicus, B. 1994. Gesten und Gebärden in Darstellungen des Alten und Mittleren Reiches. Studien zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altägyptens 10. Heidelberg: Heidelberger Orientverlag.

- Freed and Doxey 2009

- Freed, R.E., and D.M. Doxey. 2009. “The Djehutynakhts’ Models.” In The Secrets of Tomb 10A: Egypt 2000 BC, edited by Rita E Freed, Lawrence M. Berman, Denise M. Doxey, and Nicholas S. Picardo, 151–177. Boston: MFA Publications.

- Garstang 1907

- Garstang, J. 1907. Burial Customs of Ancient Egypt: As Illustrated by Tombs of the Middle Kingdom: A Report of Excavations Made in the Necropolis of Beni Hassan during 1902-3-4. London: Kegan Paul.

- Grajetzki 2014

- Grajetzki, Wolfram. 2014. Tomb Treasures of the Late Middle Kingdom: The Archaeology of Female Burials. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Jéquier 1933

- Jéquier, G. 1933. Deux Pyramides Du Moyen Empire. Cairo: l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Oritentale.

- Lokma 2001

- Lokma, N. 2001. “The Reconstruction of a Group of Wooden Models from the Tomb of Djehutinakht in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.” Bulletin of the American Research Center in Egypt 181, no. 1: 3–6.

- Meyer 2016

- Meyer, Marleen de. 2016. “An Isolated Middle Kingdom Tomb at Dayr Al-Barsha.” In The World of Middle Kingdom Egypt (2000-1550 BC): Contributions on Archaeology, Art, Religion, and Written Sources, edited by Gianluca Miniaci and Wolfram Grajetzki, 85–116. Middle Kingdom Studies 2. London: Golden House Publications.

- Nyord 2014

- Nyord, Rune. 2014. “Permeable Containers: Body and Cosmos in Middle Kingdom Coffins.” In Body, Cosmos and Eternity, edited by R. Sousa, 29-44. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Reisner 1913

- Reisner, G.A. 1913. Models of Ships and Boats. Catalogue Général des Antiquités Égyptiennes du Musée du Caire, nos. 4798–4976 and 5034–5200. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

- Serpico 2008

- Serpico, M. 2008. “Sedment.” In Unseen Images: Archive Photographs in the Petrie Museum, edited by Janet Picton and Ivor Pridden, 99–184. London: Golden House Publications.

- Smith 2008

- Smith, Mark. 2008. “Osiris and the Deceased.” UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, edited by Jacco Dielman and Willeke Wendrich. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/29r70244

- Thomas 1956

- Thomas, E. 1956. “Solar Barks Prow to Prow.” JEA 42: 65–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/3855125

- Tooley 1989

- Tooley, Angela M.J. 1989. “Middle Kingdom Burial Customs. A Study of Wooden Models and Related Material.” Ph.D. diss., University of Liverpool.