The Carlos galleries are closed to the public on Mondays, and staff take advantage of the time to get work done that would be disruptive when the museum is open. On one such Monday in 2009, a team was working in the Classical Court to install a Roman marble altar that had been reused in antiquity as a well head (2006.038.001). When we purchased the altar from London dealer Rupert Wace in 2006, it arrived with a modern base and lid. The decision was made to remove the modern additions before it went on display. The Carlos does not have the proper equipment to lift such a heavy object, so riggers had to be hired to do the work in the galleries for installation. When the riggers and Carlos staff were moving the altar, we discovered that the modern lid and base were connected by a marble inscription (2006.038.002) – a bonus object neither the Carlos or Wace had known about. The marble strut was determined to be part of a 2nd Century AD door or window frame. It was reused in the 12th Century CE and was carved with an inscription containing the names of Pope Clement III (1130-1191) and Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI (1165-1197).

The inscription had been inserted into the hollowed-out altar/well head to support the modern base and lid, most likely making it into a pedestal. But when did this work happen and who did it? According to our invoice from Rupert Wace, the altar had been in the family of Joseph Altounian (1889-1954) and was previously part of the Lansdowne Collection sold by Christie’s London on March 5, 1930. Altounian and his wife Henriette Lorbet ran Lorbet-Altounian Gallery in Mȃcon, France. Annotated catalogues from the Christie’s 1930 sale show Lorbet purchased the altar as lot 28 for £25 3s.

The Lansdowne Collection had been assembled between the mid 1760s and the late 1790s by William Petty Fitzmaurice (1737-1805), 1st Marquess of Lansdowne. Petty is perhaps most noted for securing peace with the colonies at the end of the American War of Independence when he served as Prime Minister of Great Britain. As a good English gentleman, Petty acquired a collection of antiquities for Lansdowne House, with his two main sources being Thomas Jenkins (1722-1798) and Gavin Hamilton (1723-1798). Jenkins and Hamilton were dealers, as well as diggers. They would strike an agreement with a landowner in Italy, giving them permission to dig for antiquities. If anything was found, the finds were shared with the landowner, the Vatican, and the remainder were sold by Jenkins and Hamilton. We are not sure who secured the altar for Petty, but it was ultimately used as a pedestal for a statue of Harpocrates in the Sculpture Gallery at Lansdowne House.

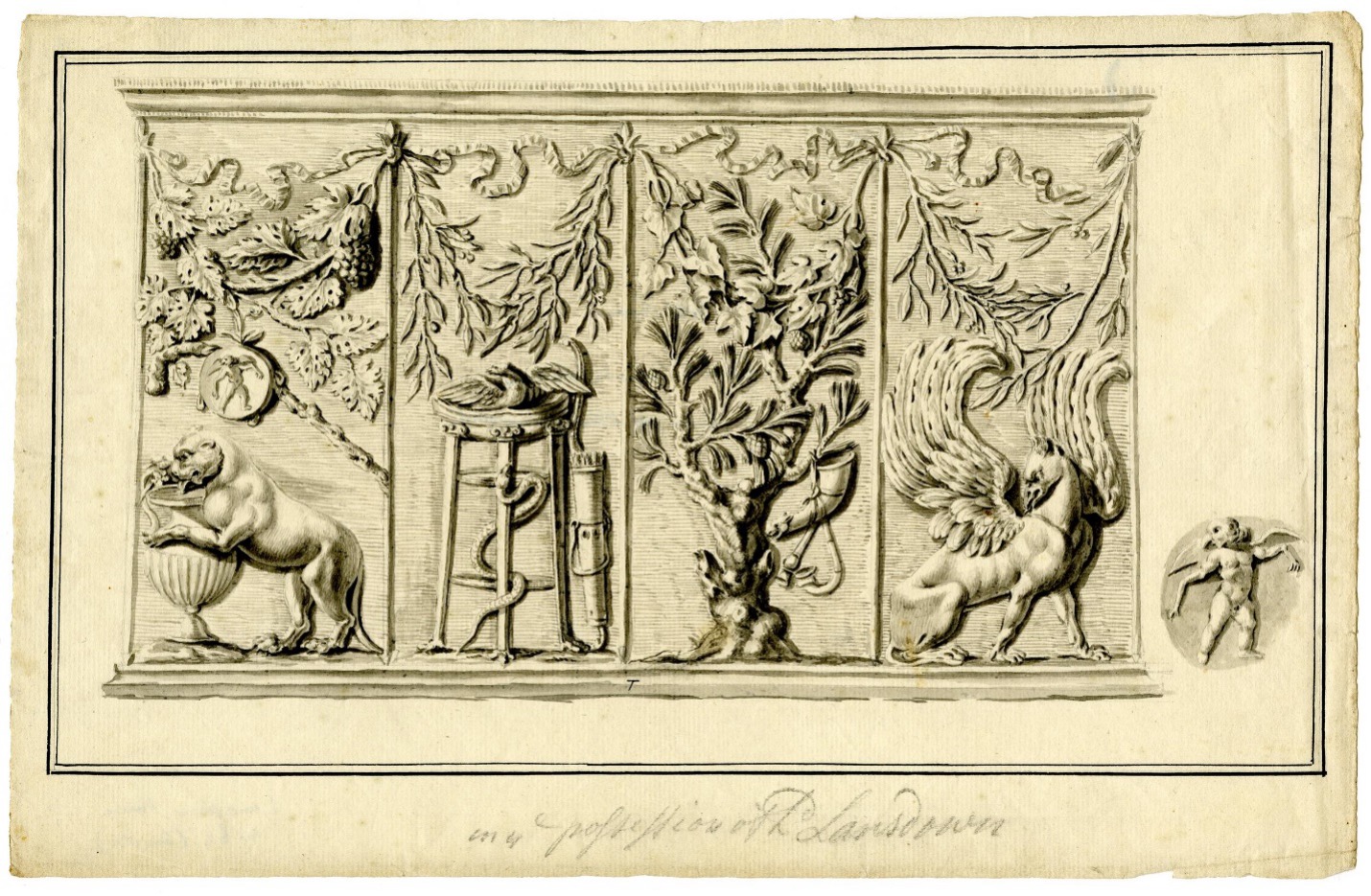

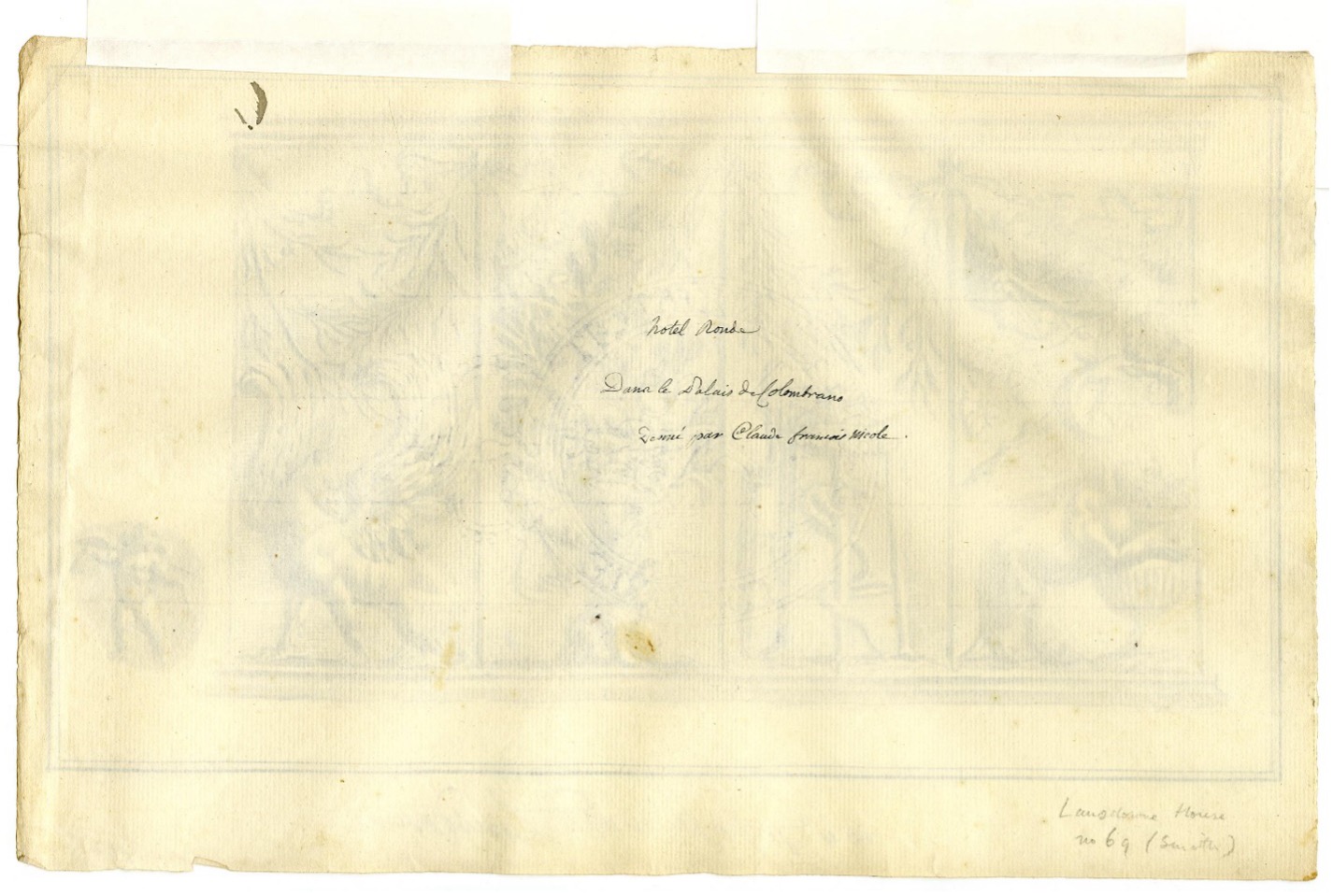

Before the altar was at Lansdowne House in London, it was drawn by Claude François Nicole I (1700-1783) in Naples. On the front is a notation made by a later owner of the drawing that the altar was in the possession of L[or]d Lansdown[e]. However, on the back of the drawing, Nicole noted the altar was located in “le Palais de Colombrano.” The Columbrano Palace in Naples, Italy, was the home of the aristocratic Carafa Family, who had been collecting antiquities since at least the early 15th Century. In the late 18th Century, the Carafa family was selling off its collection of antiquities – some of which were purchased by Thomas Jenkins and Gavin Hamilton.

While we may never be able to say for certain who turned the altar/well head into a pedestal, we do know that the altar has lived a fascinating life in three countries and two continents over the last 600 years.