Provenance research is all about filling in the life story of an object. When it comes to prints and drawings, sometimes you get a little help from past collectors. Beginning in the 17th century, collectors would often mark prints and drawings in their possession with a personalized stamped or inked mark. Today we call them “collectors’ marks”. Luckily for us, Dutch art historian Frits Lugt (1884–1970) compiled known collectors’ marks and biographies in his 1921 publication Les marques de collections de dessins et d’estampes. The work is now available online and includes thousands of entries.

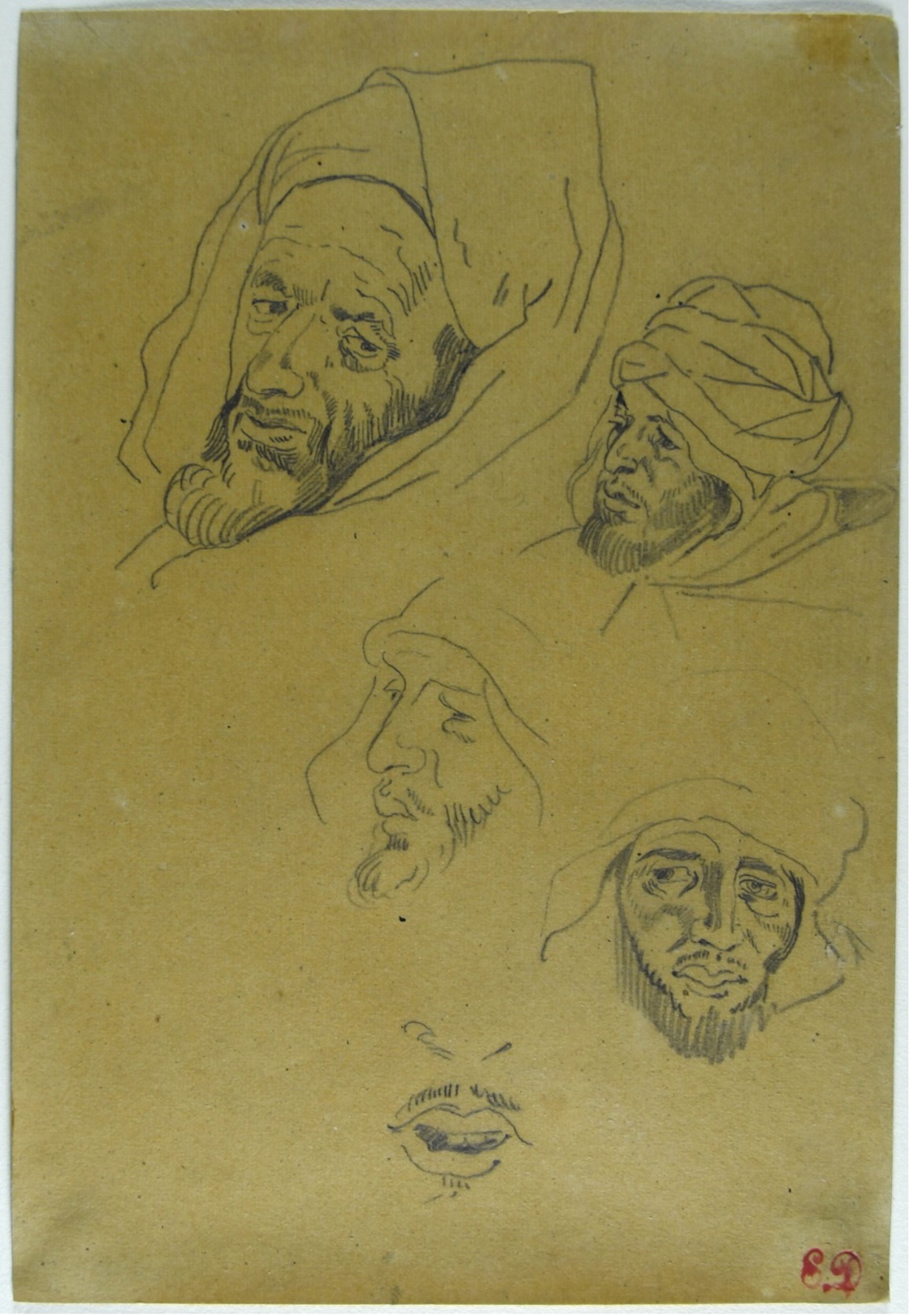

The Carlos Museum has a drawing in our Works on Paper collection that purports to be by French Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863). According to a letter written by the object’s donor in 1984, the drawing was made by Delacroix in 1832 during his travels in Morocco. Apart from saying he purchased the drawing in 1967, no other provenance information was given by the donor.

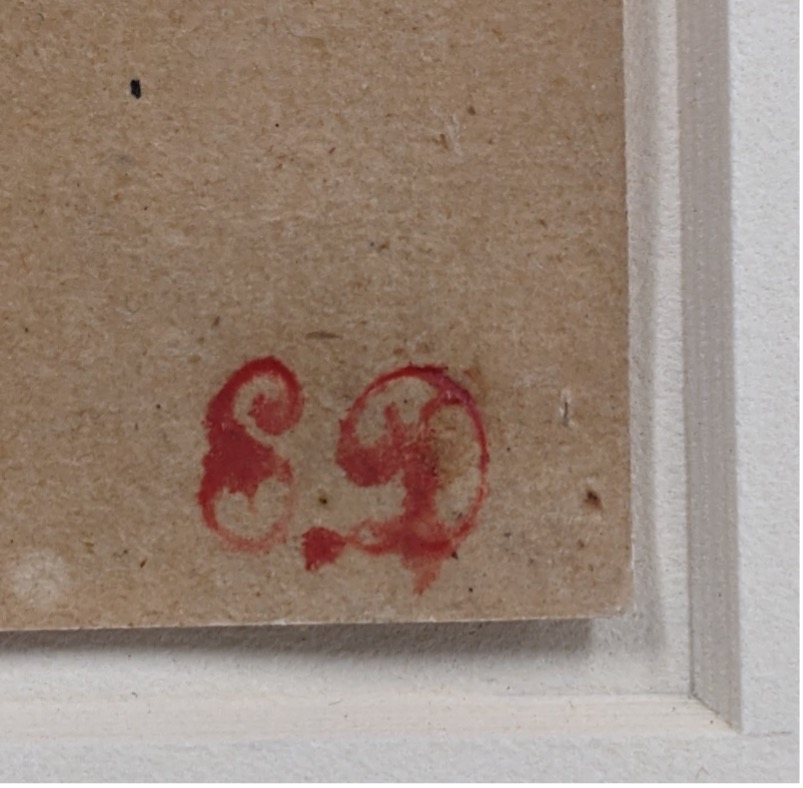

When looking at the drawing, you can see a red stamped ED in the lower right corner. Unfortunately, the ink of the stamp has bled due to what looks like water damage, but I think the stamp is L.838a. According to Lugt, this stamp was placed on all drawings that were found in Delacroix’s studio at the time of his death before they were put up for sale at Hôtel Drouot in Paris in 1864. The sweeping use of the stamp means that some of the drawings stamped with the red ED were done by people other than Delacroix. Art historians have identified several works done by one of Delacroix’s assistants, Pierre Andrieu (ca. 1821–1892), among the drawings stamped with ED.

So, we have the working hypothesis that our drawing was found in the studio of Delacroix after his death and sold in Paris in 1864. The next place to look for provenance information is in the catalogue for the posthumous sale at Hôtel Drouot that was held February 22 to 27, 1864. Looking through the entries, I found four potential matches for our drawing:

Lot 570 – Studies of Moroccan and Arab heads, 7 drawings

Lot 572 – Studies and sketches of characters, costumes, interiors, architectural details, etc., approximately 800 leaves

Lot 649 – Portraits and studies of men’s heads, from nature, watercolors, drawings, and sketches

Lot 663 – Voyage to Morocco and Spain, 7 albums

Unfortunately, none of these works are illustrated, so it is not possible to determine which, if any, of these entries refers to our drawing.

Our curator told me to also check the catalogues raisonnés of Delacroix. A catalogue raisonné is a comprehensive catalogue of all works by a given artist. The first catalogue raisonné of Delacroix’s work was compiled by French art historian Alfred Robaut (1830–1909) in 1885. There’s only one entry that could match our drawing. On page 422, No. 1643 lists “seven albums of watercolor, drawings, and notes from trip to Morocco”. These albums are Lot 663 from the 1864 Paris sale.

One last interesting detail about the provenance of our drawing can be found in the files. According to a handwritten note, the drawing came to the museum framed. The frame is long gone, but the note says there was a sticker on the back of the frame: M. Knoedler and Company, Inc. 14 East 57th Street New York, New York. Knoedler began in New York in 1846 and was one of America’s most respected galleries throughout the 20th century. That was until 2011, when Knoedler closed after becoming embroiled in a series of lawsuits related to 60 forged Abstract Expressionist paintings that had been sold at the gallery from 1995–2008 for a total of $80 million. The agent representing the works provided vague provenance details that were plausible, but no provenance research was ever carried out. For the full story, check out one of my favorite documentaries on Netflix, Made You Look: A True Story About Fake Art.