In provenance research, you come across some very interesting personalities. The Carlos has a handful of objects from one such personality: Winifred Shaughnessy. Born in 1897 to an Irish Catholic father and a wealthy Mormon mother, Winifred spent the first years of her life in Salt Lake City before moving to San Francisco with her mother after her parents divorced. Winifred, said to have been a rebellious teen, was sent to boarding school in England where she developed a love of dance and ancient mythology. These two passions would wind up shaping the rest of her life.

Winifred went to New York City in her late teens to dance with Russian choreographer Theodore Kosloff, with whom she began an affair. By age 19, Winifred, who now went by the name Natacha Rambova, had moved to Los Angeles with Kosloff to work in the emerging Hollywood film industry. Natacha quickly made a name for herself as an avant-garde costume and set designer, blending accurate historical detail with cutting-edge 1920s fashion.

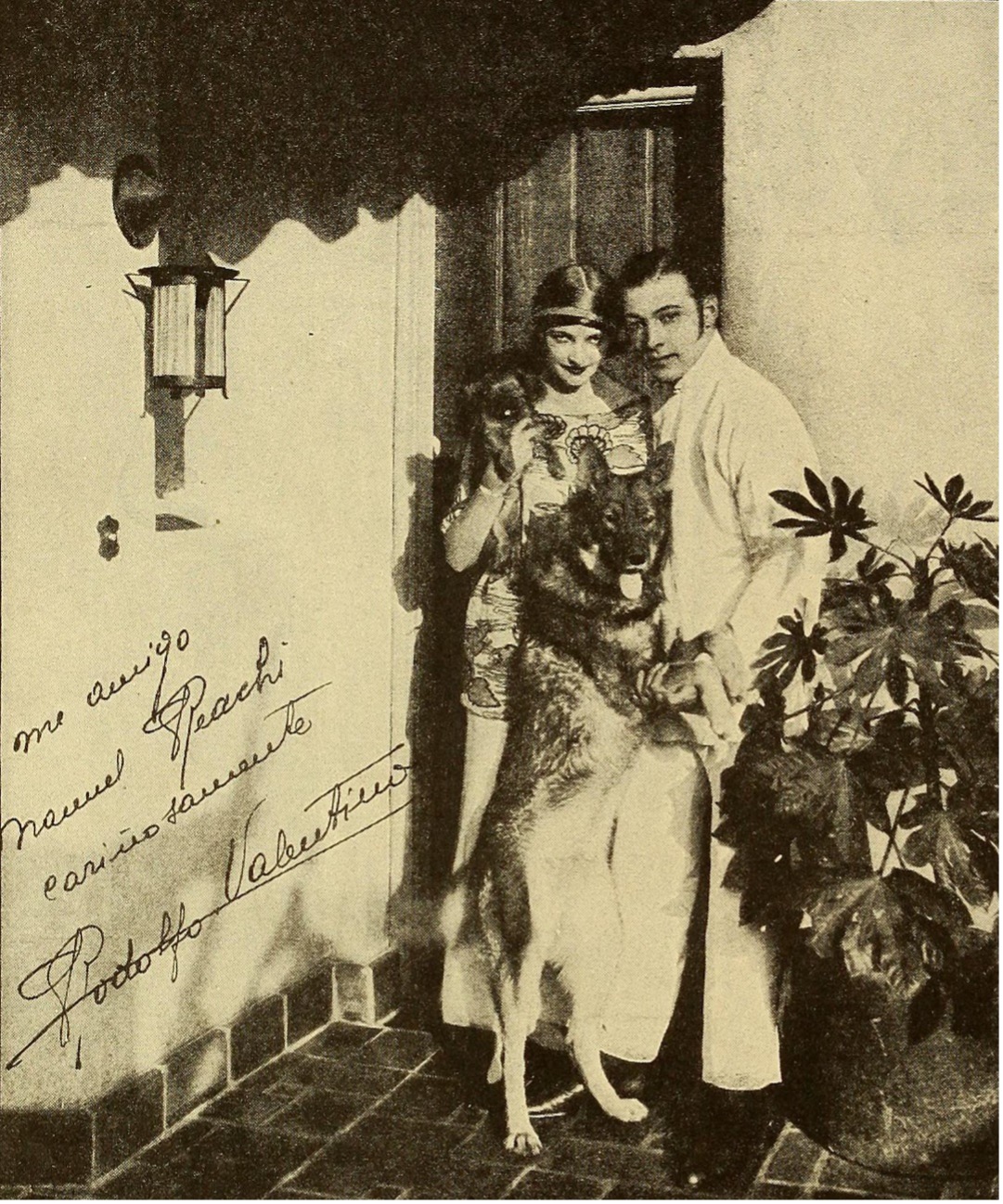

While on set, Natacha met Italian silent film legend Rudolph Valentino. The couple married in Mexico in 1922. Upon arriving back in the United States, Valentino was arrested and jailed for bigamy as it turned out Valentino’s divorce from his first wife wasn’t legally finalized. After a public trial, Natacha and Valentino’s marriage was annulled and the couple separated for a full year. The couple remarried (legally this time) in 1923, but the ending was still the same. As Valentino’s star started to decline, Natacha, who had taken a more active role in his career, was blamed. One Hollywood studio went so far as to have Valentino sign a contract that banned Natacha from his sets. The couple went through an acrimonious divorce in 1925, and when Valentino died the following year from sepsis, he left her $1 in his will.

After Valentino’s death, Natacha returned to New York City where she published her memoirs and opened a high-end clothing shop on Fifth Avenue. In 1932, Natacha closed shop and moved to Europe where she met her second husband, Spanish aristocrat Álvaro de Urzáiz. Time had not improved her taste in husbands, however, and the marriage fell apart with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. After a stay in France, Natacha was back in New York City by 1940.

Having once moved to New York City to dance, Natacha now turned to another passion from her youth—ancient mythology. In 1936, while still living in Europe, Natacha had first visited Egypt. She reportedly said being in Egypt felt like she had finally come home. Fueled by a lifelong interest in spiritualism and the possibility of past lives, Natacha threw herself into studying ancient Egyptian mythology, religion, and symbology. In 1945, she received a grant from the Old Dominion Foundation (a predecessor of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation) to pursue her research. The grant-backed research allowed Natacha to develop an understanding and appreciation for Egyptology, as well as the chance to establish strong working relationships with Egyptologists. Natacha would go on to work closely with Russian-born Egyptologist Alexandre Piankoff, helping to prepare his manuscripts on ancient Egyptian texts for publication. Natacha and Piankoff’s work, funded throughout the years by grants from the Mellon family and their Bollingen Foundation, are still used by Egyptologists today.

While in Egypt on her grant-funded work, Natacha built a personal collection of ancient Egyptian objects purchased from local dealers. Her collection was centered around objects that, for her, demonstrated a shared symbolism between Egypt and other cultures across the globe. She donated over 200 objects to The Utah Museum of Fine Arts at the University of Utah beginning in 1952. At the time of her death in 1966, Natacha did have a few objects still in her possession. They were either personal favorites or objects she was actively researching. Archaeologist Donald Hansen, a friend she met in the early 1960s when he attended her lectures on mythology and symbolism, received the objects after she passed. They ultimately hit the art market where they made their way into collections and museums like the Carlos.

I would like to extend a special thanks to the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, particularly to Luke Kelly, Associate Curator of Collections. His insights into Natacha and her collection were helpful for both this blog post and understanding more about the modern context of the Rambova objects in the Carlos’s collection.