Last month, I had the privilege of spending two weeks in Egypt. While in Luxor, I dropped by the Luxor Museum to pay a visit to a former resident of the Carlos Museum.

In 1860, Sydney Barnett made the first of three trips to Egypt. Accompanied by philanthropist Dr. James Douglas, Barnett was on a mission to acquire ancient Egyptian objects and mummies for his family’s museum in Canada. Founded in 1827, the Niagara Falls Museum boasted collections of taxidermy animals, Native American artifacts, dinosaur fossils, and barrels used by thrill seekers as they went over Horseshoe Falls.

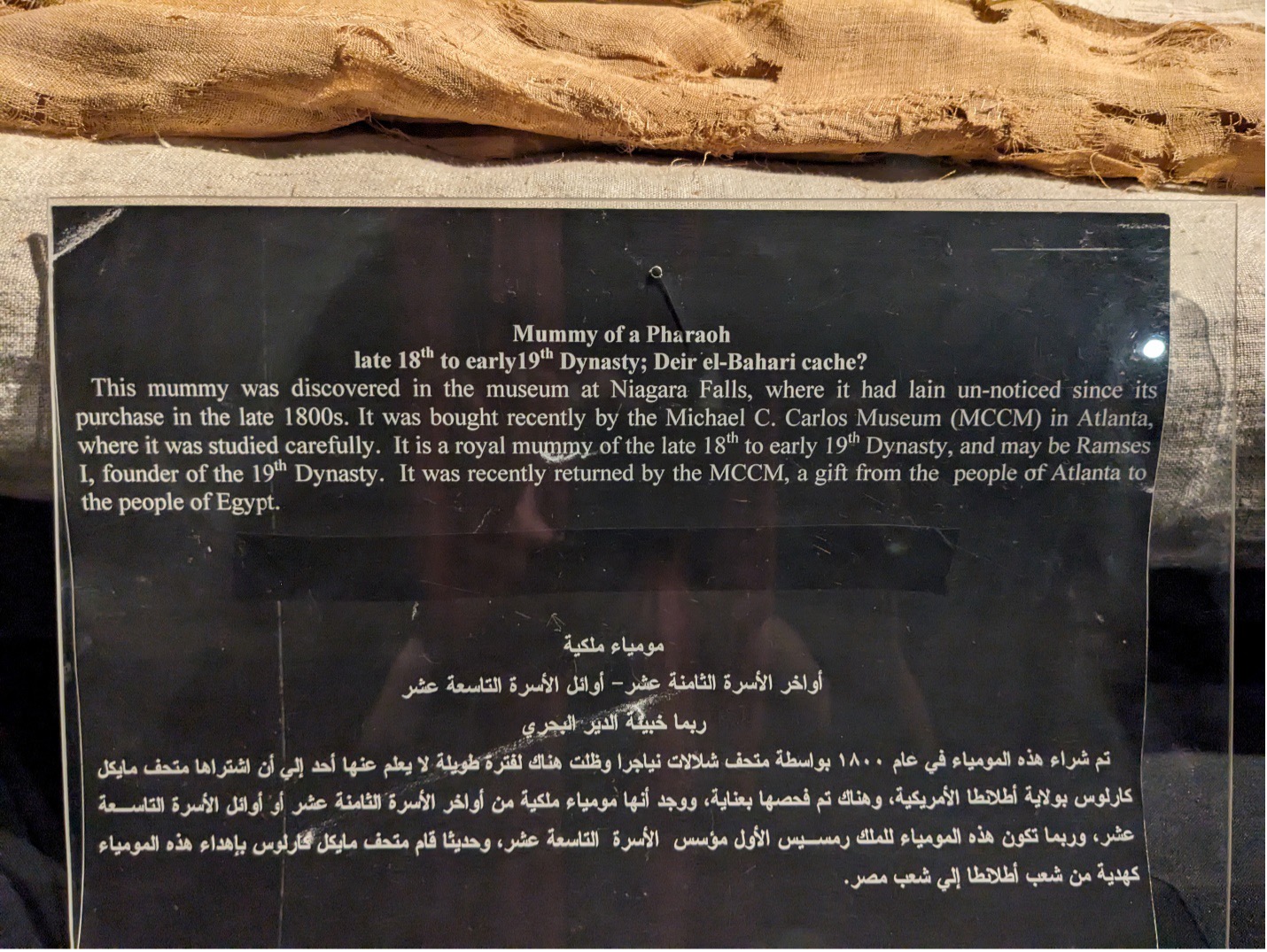

The museum ultimately closed in 1998, and the collections hit the market. The Carlos Museum recognized a rare opportunity to purchase a historic Egyptian collection that would enhance the museum’s holdings and provide new educational opportunities for Emory students and Atlanta school children. Funded in large part by donations from the people of Atlanta, the Carlos completed the purchase of over 150 objects and mummies from the Niagara Falls Museum in 1999.

Soon after their arrival in Atlanta, the nine mummies acquired by the Carlos went to Emory University Hospital for CT scans and X-rays. One of the mummies, an unwrapped male, had Egyptologists whispering among themselves for years. He enjoyed a high quality of mummification and was mummified with his arms crossed over his chest – characteristics usually seen among royal mummies during Egypt’s New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 BCE). Beginning around 600 BCE, non-royal mummies began to appear with their arms crossed over their chest, but the question remained: Could this be the mummy of a lost king of Egypt?

The mummy in question had been unwrapped long before arriving at the Carlos. Some Egyptologists remarked that his facial features bore a striking resemblance to the great Egyptian kings Seti I and Ramesses II of the 19th Dynasty (ca. 1295–1186 BCE). But we can’t identify mummies based on looks alone. Medical imaging performed at Emory’s hospital showed a male, probably over the age of 45. His teeth were overall in excellent condition, but there was an abscess in one molar. There was damage to his right ear that suggested either physical trauma or chronic ear infections.

While all of this was interesting, it did not provide proof of the mummy’s identity. The Carlos considered what other non-destructive tests could be done. DNA testing of mummies was not a proven method for determining identity, but Carbon-14 testing could provide additional data. While he was undergoing conservation treatment in the Carlos lab, conservators took the opportunity to sample the mummy. A skin sample was taken from the fourth toe of the left foot, a sample of connective tissue was taken from the right foot arch, and a sample was taken from some linen remaining on the body. The Carbon-14 testing came back with a date of ca. 409 to 185 BCE, dating the mummy to the Late Period - Ptolemaic Period, the time in Egypt when non-royals were mummified with their arms crossed over their chests.

At the end of the day, even with the Carbon-14 data, the Carlos could not conclusively state if the mummy was royal or not. Because the possibility remained that he was royalty, the Carlos made the decision to return him to Egypt. The mummy began his journey home on October 4, 2003, and was ultimately given his own private suite at the Luxor Museum, where I visit him every time I’m in town.