Introduction

English

NARRATOR: Welcome to Picture Worlds: Greek, Maya, and Moche Pottery. Through these ancient vessels you’ll encounter cultures and worlds now far from us in time. How can you begin to understand the visual stories they tell from such a distance? Your guides on this journey are contemporary artists and scholars who are inspired by these objects, and the cultures that made them. So let’s begin.

Introduction

Spanish

NARRACIÓN: Les damos la bienvenida a Imaginando mundos: Cerámica griega, maya y mochica. Estas antiguas vasijas le permitirán conocer culturas y mundos que ahora están alejados de nosotros en el tiempo. ¿Cómo entender las historias de civilizaciones tan remotas? Sus guías en este viaje son artistas contemporáneos y estudiosos que se inspiran en estos objetos y en las culturas que los fabricaron. Comencemos.

Drinking Vessel with a Palace Scene

English

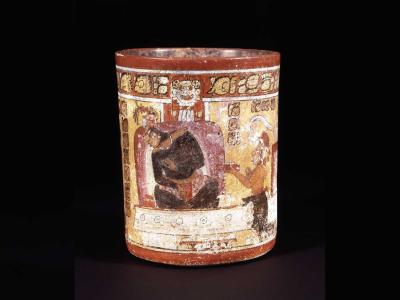

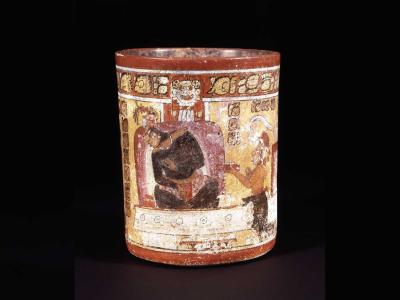

Drinking Vessel with a Palace Scene, Maya, 650–750 CE, Signed by Kuluub as painter. Ceramic. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Pre-Columbian Collection, Washington, D.C. Image: © Dumbarton Oaks, Pre-Columbian Collection, Washington, D.C.

NARRATOR: The Maya, Moche, and Greeks made and used painted pottery in many different ways—for drinking and ceremonies, as gifts, and as offerings. In all three cultures, these vessels were part of social life. They used these vessels to share the stories important to them, although we may not understand them today.

The Maya vessel shows two figures deep in conversation, perhaps aided by the drinking cup that one of them holds; the Moche piece depicts vessels that seem to accompany weavers as they work; while the Greek cup pictures men enjoying wine at a drinking party.

Contemporary Pueblo potter Diego Romero makes ceramic bowls that tell stories through pictures. For him, all art is a way to communicate.

DIEGO ROMERO: What is narrative? Narrative is the human story, so It seems to me that human beings have a need for this.

Drinking Vessel with a Palace Scene

Spanish

Drinking Vessel with a Palace Scene, Maya, 650–750 CE, Signed by Kuluub as painter. Ceramic. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Pre-Columbian Collection, Washington, D.C. Image: © Dumbarton Oaks, Pre-Columbian Collection, Washington, D.C.

NARRACIÓN: Los mayas, los mochicas y los griegos creaban y pintaban cerámica de distintas maneras según el uso: para beber, celebrar ceremonias, obsequiar o hacer ofrendas. En las tres culturas, estas vasijas formaban parte de la vida social. Al igual que las pantallas de cine o los lienzos de los artistas contemporáneos que cuentan una historia, estas culturas usaban el interior y exterior de las vasijas para contar historias importantes, a pesar de que no las entendamos en la actualidad.

La vasija maya muestra dos figuras inmersas en una conversación, tal vez amenizada por la copa que sostiene una de ellas. La pieza mochica representa las vasijas que parecen acompañar a las tejedoras mientras trabajan. Y en la copa griega se pueden ver hombres disfrutando del vino en una reunión de bebedores.

NARRACIÓN: Diego Romero, ceramista contemporáneo pueblo, elabora cuencos de cerámica que narran historias por medio de imágenes. Según el artista, toda forma de arte es una manera de comunicarse.

DIEGO ROMERO: ¿Qué es la narrativa? Es la historia de la humanidad. En mi opinión, los seres humanos tienen necesidad por ella.

Cup with Helen and Menelaos between Battle Scenes

English

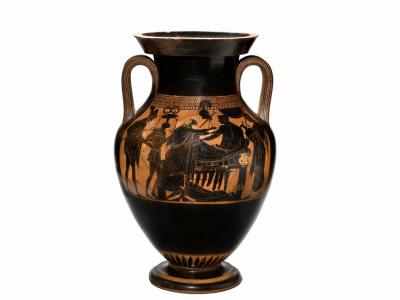

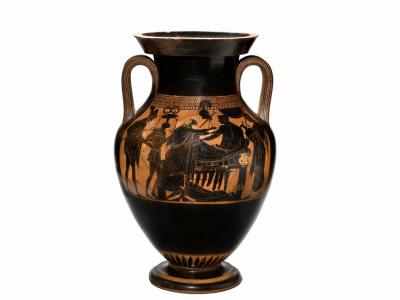

Cup with Helen and Menelaos between Battle Scenes, Greek, 540–530 BCE. Terracotta. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund, 1944, 44.11.1.

NARRATOR: The tale painted on this vase would have been well-known to people in ancient Greece, but not because they had read it.

ELENI HASAKI: Most of the people in antiquity couldn’t read. Reading was for 10% of the elite households. In our ancient communities, everyone would have listened to them, because they were performed as oral poetry.

NARRATOR: That’s Archaeology professor Eleni Hasaki. This drinking cup shows the moment when King Menalaos recovers his wife Helen at the end of the Trojan War. Helen was considered the most beautiful woman in the world, and her kidnapping by Paris is said to have started the war. A privileged man in Ancient Greece might have used this cup at a symposion, or drinking party, where men gathered to enjoy each other’s company, food, and wine. As the person imbibing from this vessel empties it, another message is revealed.

HASAKI: A lot of drinking is happening in parties. The users almost transform themselves after consuming a certain amount of wine. As you pick it up from its handles and you drink, by the time you come to the end, the entire vessel has come in front of your face. And indeed it can be used as a mask.

NARRATOR: In between vignettes of figures are large, piercing eyes, which in ancient Greece, and even today in many parts of the Mediterranean, may be considered protective against those who wish you evil.

HASAKI: The power of the eyes looking straight on you and provoking fear and projecting power. We have a term for that, called “apotropaic,” keeping away the evil. The evil eye, down to our days in various cultures, at least from my part of the world, it protects you, and it frightens the viewer, who may be your enemy. We have some apotropaic eyes in our home too from Greece.

Cup with Helen and Menelaos between Battle Scenes

Spanish

Cup with Helen and Menelaos between Battle Scenes, Greek, 540–530 BCE. Terracotta. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund, 1944, 44.11.1.

NARRACIÓN: Seguramente, la gente de la antigua Grecia conocía bien la historia ilustrada de este jarrón, pero no porque la hubiesen leído.

ELENI HASAKI: La mayoría de las personas de la antigüedad no sabía leer. Solo el 10 % de las familias de clase alta sabían leer. En las comunidades antiguas, las personas solo escuchaban las historias, gracias a que eran transmitidas por medio de la poesía oral.

NARRACIÓN: Ella es la profesora de arqueología Eleni Hasaki. Esta copa muestra el momento en que el rey Menelao recupera a su esposa Helena al final de guerra de Troya. Helena era considerada la mujer más hermosa del mundo, y se dice que la guerra comenzó cuando fue secuestrada por Paris. Un hombre privilegiado de la antigua Grecia pudo haber utilizado este recipiente en un simposio —o reunión para beber—, donde los hombres se reunían para disfrutar de la compañía mutua, la comida y el vino. Cuando la persona que bebía de la copa se terminaba el vino, se revelaba otro mensaje.

HASAKI: La gente bebía mucho en esas fiestas. Se podría decir que quienes bebían se transformaban tras consumir una determinada cantidad de vino. Bebían tomando la copa por las asas, y al terminar, el rostro quedaba oculto detrás del recipiente. Daba la impresión de que usaban una máscara.

NARRACIÓN: Entre las viñetas de las figuras, se ven unos ojos grandes y penetrantes, que en la antigua Grecia —e incluso hoy en muchas partes del Mediterráneo— pueden considerarse una protección contra quienes nos desean el mal.

HASAKI: Los ojos nos miran directamente; producen miedo y proyectan poder. Tenemos una palabra para esto: “apotropaico”, que es sinónimo de alejar el mal. Es el concepto de “mal de ojo” en varias culturas, al menos de la parte del mundo donde nací. Te protege y amedrenta a quien lo ve, que puede ser tu enemigo. Tenemos ojos apotropaicos de Grecia en nuestro hogar también.

Vessel with a Mother, a Baby, and a Curer

English

Vessel with a Mother, a Baby, and a Curer, Moche, 300–450 CE. Terracotta. Complejo Arqueológico El Brujo-Museo Cao. Ministry of Culture of Peru. Image courtesy Ministerio de Cultura, Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú, Lima/Museo Cao

NARRATOR: This Moche vessel shows a woman holding a baby while being visited by a “curandera,” or woman healer. It was found in a tomb of a young woman of high status. In fact, many of the objects in these galleries were probably found in burial sites, but not everyone is comfortable with the display of these objects in museums. Peruvian-American artist, Kukuli Velarde.

KUKULI VELARDE: These pieces were mostly dedicated to burials, so they were not going to be seen. They were serving a different way of looking at the world. The stories that they were telling on these surfaces, were they to be narrated to those who are not here anymore, or to entities that they revered, we don't really know.

NARRATOR: While archaeologists who study these objects try to decode their meaning, Velarde is dubious about this project.

Vessel with a Mother, a Baby, and a Curer

Spanish

Vessel with a Mother, a Baby, and a Curer, Moche, 300–450 CE. Terracotta. Complejo Arqueológico El Brujo-Museo Cao. Ministry of Culture of Peru. Image courtesy Ministerio de Cultura, Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú, Lima/Museo Cao

NARRACIÓN: La vasija mochica representa a una mujer cargando un bebé mientras la visita una curandera. La pieza fue encontrada en la tumba de una mujer joven de alto estrato social. De hecho, probablemente muchos objetos de esta galería fueron hallados en cementerios, pero no todo el mundo se siente a gusto cuando ve estos artículos expuestos en museos. Artista peruanoestadounidense Kukuli Velarde.

KUKULI VELARDE: Estas piezas se fabricaron para entierros, no para ser vistas. Las hacía una persona. En la mente del creador, no era algo que se mostraría ni que se expondría al público. Es una mentalidad completamente diferente a la nuestra. Es una visión del mundo distinta. Y las historias que contaban en estas superficies eran para contárselas a quienes ya no están aquí, o a entidades que ellos veneraban y que no conocemos del todo.

NARRACIÓN: Si bien los arqueólogos que estudian estos objetos buscan descifrar su significado, Velarde cuestiona dichos intentos.

VELARDE: Muchos misterios se resolverían si simplemente aceptamos el hecho de que no los entenderemos, y que nunca satisfaremos por completo esa necesidad que tenemos de buscarle una explicación a todo. Y eso está bien, porque es importante también mantener vivas las distintas formas de pensar. De lo contrario, estaríamos dando por hecho que no tenemos diferencias.

Drinking Vessel with Maize God Dancers and a Companion

English

Drinking Vessel with Maize God Dancers and a Companion, Maya, 650–750 CE. Slip-painted ceramic. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Purchased with funds provided by Camilla Chandler Frost. Digital Image: © 2024 Museum Associates / LACMA.

NARRATOR: While ancient Greeks used decorated cups for drinking wine, the Maya favored cacao, at least for the elite members of society. The text around the rim of this cup indicates it was made for a female ruler named Lady Kaloomte.

IYAXEL COJTI REN: Precious objects were tagged with dates and names to reflect the ownership, saying that this vessel is for this specific function and belongs to this person. Also, sometimes it provides the name of the scribe who made the painting, the decoration. Still today in Maya communities it’s like blessing a cherished artifact in a spiritual way.

NARRATOR: That’s Iyaxel Cojti Ren, a K’iche archaeologist from Guatemala and professor of anthropology at the University of Texas in Austin. Underneath the dedicatory inscription, two figures of the Maize God are dancing with a small person.

COJTI REN: We don’t know the exact meaning of that scene, but what we know now is that the Maize God can have different roles. It can play an important role in Maya spirituality, but also in Maya politics.

NARRATOR: Diego Romero is a contemporary Pueblo ceramicist. One of the stories the pot reveals to him is the talent of the artist.

DIEGO ROMERO: Look at the hands and the feet. And those people did not have stuff like computers to go in and edit. That’s all hand-painted with a single stroke. It’s hand painted with such confidence and such a knowledge of the human body and anatomy. I think the Mayans were some of the greatest painters of humanity of all time.

Drinking Vessel with Maize God Dancers and a Companion

Spanish

Drinking Vessel with Maize God Dancers and a Companion, Maya, 650–750 CE. Slip-painted ceramic. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Purchased with funds provided by Camilla Chandler Frost. Digital Image: © 2024 Museum Associates / LACMA.

NARRACIÓN: Aunque en la antigua Grecia se usaban copas decoradas para beber vino, los mayas preferían el cacao, al menos para los miembros de la alta sociedad. El texto ubicado alrededor del borde de esta copa indica que fue fabricado para una reina de Bax Witz (llamada Ixik Kaloomte’ Ixik We’om Yohl Ch’een).

COJTI REN: Algunos objetos preciosos se marcaban con fechas y nombres para [23:30] indicar que tenían dueño. Señalaban que el artículo cumplía una función [24:00] específica y pertenecía a alguien en particular. Además, en ocasiones incluía el nombre del escriba que los había pintado o decorado.

NARRACIÓN: Ella es Iyaxel Cojti Ren, arqueóloga k'iche de Guatemala y profesora de antropología de la University of Texas en Austin. Debajo de la inscripción dedicatoria, se pueden ver dos figuras del Dios del Maíz danzando con una pequeña persona.

COJTI REN: No sabemos con certeza el significado de esta escena, pero sabemos que el Dios del Maíz tenía distintos roles. Desempeñaba un papel importante en la espiritualidad maya, pero también en la política de esa civilización.

ROMERO: Creo que los mayas estaban entre los mejores pintores de la historia de la humanidad.

NARRACIÓN: Diego Romero es un artista pueblo contemporáneo.

ROMERO: Mire las manos y los pies. No tenían una computadora para editar la obra. Todo era pintado a mano con un solo trazo. Estaba todo pintado a mano con mucha seguridad y conocimiento del cuerpo humano y su anatomía.

Storage Jar with the Ransom of Hektor

English

Storage Jar with the Ransom of Hektor, Greek, 520–510 BCE, attributed to the Rycroft Painter. Wheel-thrown, slip-decorated earthenware. Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. Purchased with funds from the Libbey Endowment. Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey, 1972.54 Photo: Richard Goodbody, New York

NARRATOR: Throughout time, war has been a popular subject for storytelling. Here, we recognize the pain of Trojan king Priam who crosses enemy lines to recover the body of his son Hektor after the Greek hero Achilles dragged it around the walls of the fortified city of Troy.

ELENI HASAKI: Here you see Achilles on the winning side, relaxing, having in front of him different cuts of meat and enjoying perhaps a little bit of wine.

NARRATOR: Eleni Hasaki.

HASAKI: Right next to him is the deceased body of Hektor, and then his father comes and asks for it. It's a convergence of opposite feelings, a very relaxed warrior and a very anxious father, Priam, who comes and begs. You can see how he comes with all the gifts. And all he asks is, "Can you let me give my son the required funerary rights?" It’s powerful.

Storage Jar with the Ransom of Hektor

Spanish

Storage Jar with the Ransom of Hektor, Greek, 520–510 BCE, attributed to the Rycroft Painter. Wheel-thrown, slip-decorated earthenware. Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. Purchased with funds from the Libbey Endowment. Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey, 1972.54 Photo: Richard Goodbody, New York

NARRACIÓN: A lo largo del tiempo, la guerra se volvió un tema popular en la narración de historias. Aquí, se hace aparente el dolor del rey troyano Príamo, quien atravesó las líneas enemigas para recuperar el cuerpo de su hijo Héctor después de que el héroe griego Aquiles lo arrastrara por las murallas de la ciudad fortificada de Troya.

ELENIA HASAKI: Aquí pueden ver a Aquiles, en calma, celebrando la victoria con varios cortes de carne delante de él y bebiendo algo de vino. Justo a su lado se encuentra el cadáver de Héctor, cuyo padre llegaría más tarde a reclamar el cuerpo. Se trata de la convergencia de sentimientos opuestos: un guerrero distendido y un padre muy alterado, Príamo, quien llega y suplica. Se puede observar que llega con una gran cantidad de obsequios, y lo único que pide es poder concederle a su hijo los derechos funerarios. Es impactante.

Stirrup-Spout Vessel with the Burial Theme

English

Stirrup-Spout Vessel with the Burial Theme, Moche, 650–800 CE. Terracotta. Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Herbert L. Lucas Jr. Photo: Donald Cordy

NARRATOR: This stirrup spout vessel is painted with delicate, detailed lines that tell a story. As you examine them, you might try to make sense of what is happening. Just below the stirrup spout, the body of a woman is set upon by birds.

KUKULI VELARDE: This woman seems as if she were giving birth. Oh, no. This body is dead and these are vultures that are taking the body. When I look at this, and I know that there were a lot of wars and human sacrifices, I wonder—how was it to live in a reality like that? And it doesn't matter how much I try to imagine, I can't. And I like the idea of not knowing, because when we think that we know, we limit knowledge. We think that everything can be explained.

NARRATOR: For Velarde, who, like many Peruvians, traces part of her ancestry to the country’s indigenous cultures, the lack of explanation doesn’t make her feel farther away from the pots and their makers, but closer.

VELARDE: Since we were kids we see them all the time, everywhere. They are familiar. You know that the person who did it could have been you, hundreds of years ago. I see them as part of a narrative to which I have rights as the new blood, as all Peruvians are. I think it’s an aesthetic that belongs to our body, that belongs to our landscapes. And even if we cannot fully understand it, we have the possibility of continuing it.

Stirrup-Spout Vessel with the Burial Theme

Spanish

Stirrup-Spout Vessel with the Burial Theme, Moche, 650–800 CE. Terracotta. Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Herbert L. Lucas Jr. Photo: Donald Cordy

NARRACIÓN: ¿Qué es lo primero que le llama la atención de este recipiente con asa estribo? ¿La forma? ¿La decoración? La artista peruanoestadounidense Kukuli Velarde se fijó en el brillo.

VELARDE: La pieza está encerada. Está observando la pieza a través de los ojos del coleccionista, ya que coincide con su estética en términos de cómo se podría mejorar la pieza, y la mejora con cera.

NARRACIÓN: Velarde sugiere que encerar estos objetos después de haberlos excavado los hizo más atractivos para los coleccionistas que los adquirieron como piezas de arte. Además, esta botella con asa de estribo está pintada con líneas delicadas y minuciosas que cuentan una historia. Obsérvelas e intente descifrar su significado. Del otro lado, justo debajo del asa de estribo, se ven aves posadas alrededor del cuerpo de una mujer.

VELARDE: Pareciera que la mujer estuviera por dar a luz. Pero no es así; está muerta, y las aves son buitres que están devorando el cadáver. Cuando miro esta escena, consciente de que se libraban muchas guerras y de que se realizaban sacrificios humanos, me pregunto cómo era vivir en una realidad como aquella. Y, sin importar lo mucho que intento imaginarlo, se me hace imposible. Me gusta la idea de no saber porque, cuando pienso que tenemos el conocimiento, lo limitamos y damos por hecho que todo tiene una explicación. NARRACIÓN: Para Velarde, que, al igual que muchos peruanos, parte de su ascendencia se remonta a las culturas indígenas del país, la falta de explicación no la hace sentirse más alejada de su estirpe sino más cerca.

VELARDE: Desde la infancia, vemos estas escenas todo el tiempo, nos resultan familiares. Sabemos que la persona que hizo esto pudo haber sido cualquiera de nosotros cientos de años atrás. Las considero como parte de una narrativa que pertenece a un mundo al que tengo derecho porque somos sus descendientes, al igual que todos los peruanos. Creo que su estética es un reflejo de nuestro cuerpo y nuestros paisajes. Incluso si no podemos comprenderla del todo, tenemos la posibilidad de continuarla.

Plate with the Rebirth of the Maize God

English

Plate with the Rebirth of the Maize God, Maya, 600–800 CE. Ceramic with polychrome slip. Princeton University Art Museum, New Jersey. Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund, 1997-465.

NARRATOR: At the center of this Maya plate, the youthful and strong Maize God dances atop a skull in the underworld. In the Maya world view, or cosmovision in Spanish, he represents resurrection and renewal.

IYAXEL COJTI REN: The Maize God is one of the most important deities in Maya cosmovision because the maize was the food staple across Mesoamerica, not only in the Maya region. And usually sacred. The maize plant is also depicted as a living being.

NARRATOR: Maize, a kind of corn in South America, was central to Maya depictions, and their diet. Ancient Mayans might have put tamales in a bowl like this, a sacred connection between humans and gods.

COJTI REN: Creation usually is connected with the emergence of the Maize God from a body of water.

NARRATOR: The depiction of the Maize God as part of the annual cycle of harvest and renewal connects him with the contemporary descendants of the Mayans. The celebration of the harvest is not an ancient story, but a lived experience.

COJTI REN: I see Maya ceramics as part of our cultural heritage. I think that indigenous people today understand very well that in every culture there are continuities and transformations. There are cultural practices that are gone, but there are others that are still alive. I think that archaeology is a good way to connect past and present, and also to strengthen the identity of indigenous people today.

Plate with the Rebirth of the Maize God

Spanish

Plate with the Rebirth of the Maize God, Maya, 600–800 CE. Ceramic with polychrome slip. Princeton University Art Museum, New Jersey. Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund, 1997-465.

NARRACIÓN: En el centro de este plato maya, el joven y poderoso Dios del Maíz baila sobre una calavera en el inframundo. En la cosmovisión maya, representa la resurrección y la renovación.

COJTI REN: El Dios del Maíz es una de las deidades más importantes de la cosmovisión maya porque, además de ser sagrado, el maíz era un alimento básico en toda Mesoamérica, no solo en la región maya. La planta de maíz también se representa como un ser vivo.

NARRACIÓN: El maíz ocupaba un lugar central en las representaciones mayas y en su dieta. Es probable que los antiguos mayas hayan puesto tamales en un cuenco como este, una conexión sagrada entre humanos y dioses.

COJTI REN: La creación suele relacionarse con la aparición del Dios del Maíz de una superficie con agua.

NARRACIÓN: La representación del Dios del Maíz como parte del ciclo anual de la cosecha y la renovación lo conecta con los descendientes contemporáneos de los mayas. La celebración de la cosecha no es una historia antigua, sino una experiencia vivida.

COJTI REN: Considero que la cerámica maya es una parte de nuestro patrimonio cultural, y creo que en la actualidad las personas indígenas entienden muy bien que en toda cultura hay continuidades y transformaciones. Hay prácticas culturales que han desaparecido, pero hay otras que siguen vivas. Creo que la arqueología es una excelente manera de conectar el pasado y el presente, y también de reforzar la identidad de los pueblos indígenas actuales. Al recuperar más información, podremos reforzar nuestra identidad y nuestras prácticas culturales.

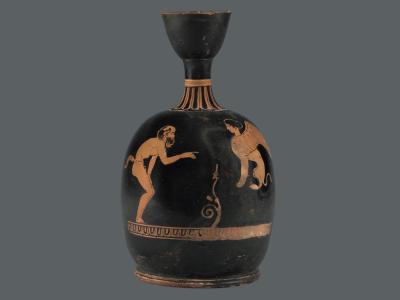

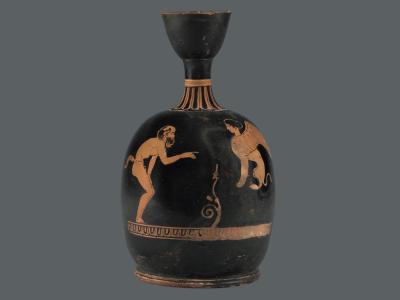

Oil Jar with a Satyr and Sphinx

English

Oil Jar with a Satyr and Sphinx, Greek, 425–420 BCE, attributed to Polion. Terracotta. Getty Museum

NARRATOR: Hybrid creatures populate Moche, Maya, and Greek pottery.

DIEGO ROMERO: Humans have this ability to imagine things that don't exist. And this is an integral part of our storytelling throughout history.

NARRATOR: That’s contemporary pueblo artist Diego Romero.

ROMERO: The hybrid shows up in all cultures at all different periods of times, and even currently in cinema and movies today. It's a very fundamental part of human imagination. What would a human and a pig look like?

NARRATOR: Which brings us to the helmeted Moche bean warriors.

ROMERO: This anthropomorphized hybrid bean. He's carrying a shield, and he has a quiver of spears. And it looks like he has an ax head that is dangling from his backside, which to me, would be very important, as probably they didn't have very many metal axes. Only someone of great importance and power would wield such an object. He's this hybrid bean. He's spotted, he has a headdress, which is equated to status. I don't know if it means he's a king; maybe he is though. Maybe he's the king of beans.

NARRATOR: As for the pot’s narrative approach, it reminds Romero of a superhero from the comic books that have inspired his own work, a character whose superpower is speed.

ROMERO: You know what I think, looking at it now? I think that this is one bean and not several beans, but I think you know how they draw the Flash, and the Flash has multiples that follow him. I think this is like a bean running around the pot, and those are all like multiples of him. And that we're looking at, in a stop-motion camera, that this is actually not several beans, but just one specific bean running around and around the pot, much in the manner that the Flash does.

NARRATOR: What is your interpretation of this bean warrior?

Oil Jar with a Satyr and Sphinx

Spanish

Oil Jar with a Satyr and Sphinx, Greek, 425–420 BCE, attributed to Polion. Terracotta. Getty Museum

NARRACIÓN: Las criaturas híbridas abundan en la cerámica mochica, maya y griega.

DIEGO ROMERO: La humanidad tiene la habilidad de imaginar cosas que no existen. Y esta es una parte fundamental de nuestra narración de relatos a lo largo de la historia.

NARRACIÓN: Es el artista pueblo contemporáneo Diego Romero.

ROMERO: Lo híbrido aparece en todas las culturas y en todas las épocas, incluso en la actualidad, en el cine y las películas. Es una parte fundamental de la imaginación humana. ¿Qué aspecto tendría un ser mitad humano, mitad cerdo?

NARRACIÓN: Lo que nos lleva a los guerreros pallares mochica con casco.

ROMERO: Este pallar híbrido antropomorfizado lleva un escudo y una aljaba con lanzas. Y parece que tiene una cabeza de hacha que cuelga de su espalda, lo que, para mí, sería muy importante, ya que seguramente no tenían muchas hachas de metal. Solo alguien de gran importancia empuñaría tal objeto. Lleva un tocado, lo que equivale a estatus. No sé si significa que es un rey; aunque quizá lo sea. Tal vez es el rey de los pallares.

NARRACIÓN: En cuanto al planteamiento narrativo del recipiente, a Romero le recuerda a un superhéroe de los cómics que ha inspirado su propia obra, un personaje cuyo superpoder es la velocidad.

ROMERO: ¿Saben lo que pienso mientras lo miro? Creo que se trata de un pallar y no de varios. Es como cuando dibujan a The Flash corriendo y pareciera que son varios. Creo que es un pallar que corre alrededor del recipiente, y los otros no son más que él mismo muchas veces. Es como una cámara de stop-motion. En realidad, no se trata de varios pallares, sino de un solo pallar específico que da vueltas alrededor del recipiente, de forma muy parecida a como lo hace Flash.

NARRACIÓN: ¿Cuál es su interpretación de este guerrero pallar?

Vessel in the Form of a Warrior Duck

English

Vessel in the Form of a Warrior Duck, Moche, 500–650 CE. Terracotta, with mother of pearl inlay. Museo Arqueológico “Santiago Uceda Castillo.” Ministry of Culture of Peru

NARRATOR: This exhibition celebrates the making of narrative ceramics in three cultures: the Maya, the Moche, and the Greek. Yet there are limitations to experiencing objects like these in a museum says archaeology professor Eleni Hasaki.

ELENI HASAKI: They were not meant to be exhibited. They were meant to be used and held and passed around.

NARRATOR: Cultures around the world are now asking that excavated cultural objects displayed in museums be returned to the places and cultures where they were found, or to their descendants, if it is possible. Today, museums struggle with questions about what can be displayed, and how to treat objects excavated from unknown tombs.

Peruvian ceramicist Kukuli Velarde wishes for something more for the objects which cannot be returned to their original tombs.

KUKULI VELARDE: I think the idea to me would be if we can see all these pieces in all the museums, but replicas. And then the pieces can go back to the darkness of a burial where they belong. I think that would be beautiful.

NARRATOR: Replicas can allow visitors to hold objects and feel the weight of them, but it doesn’t change the view of them as objects. K’iche archaelogist Iyaxel Cojti Ren, asks that visitors do a bit more.

IYAXEL COJTI REN: I would like people to remember and keep in mind that the people who are depicted on those vessels were human beings, and not artifacts. I would like them to see us as human beings and not as simple objects or works of art, always talking about societies and human beings or historical characters more than just works of art or fancy objects depicted in museums.

Vessel in the Form of a Warrior Duck

Spanish

Vessel in the Form of a Warrior Duck, Moche, 500–650 CE. Terracotta, with mother of pearl inlay. Museo Arqueológico “Santiago Uceda Castillo.” Ministry of Culture of Peru

NARRACIÓN: Esta exposición celebra la creación de cerámicas narrativas en tres culturas: la maya, la mochica y la griega. Sin embargo, según la profesora de arqueología Elena Hasaki, conocer este tipo de objetos en un museo tiene sus limitaciones.

ELENA HASAKI: No se hicieron para exponerse, sino para usarse, sostenerse y pasarse a otras personas.

NARRACIÓN: Las culturas de diferentes partes del mundo ahora exigen que los objetos culturales excavados que se exponen en los museos se devuelvan a los lugares y culturas donde se encontraron o, en lo posible, a sus descendientes. Hoy en día, los museos se enfrentan a desafíos como decidir qué se puede exponer y cómo tratar los objetos excavados en tumbas desconocidas.

La ceramista peruana Kukuli Velarde desea algo más para los objetos que no pueden ser devueltos a sus tumbas originales.

KUKULI VELARDE: Para mí, lo ideal sería que se expusieran réplicas de todas estas piezas, y que las originales puedan volver a la oscuridad de una tumba, donde pertenecen. Sería maravilloso.

NARRACIÓN: Las réplicas pueden permitir al público sostener los objetos y sentir su peso, pero no cambian la perspectiva sobre ellos. El arqueólogo quiché Iyaxel Cojti Ren pide al público que haga un poco más. COJTI REN: Me gustaría que la gente recordara y tuviera presente que las personas que aparecen representadas en esas piezas eran seres humanos, no artefactos. La gente debe hablar de sociedades, seres humanos o personajes históricos más que de obras de arte u objetos lujosos de museos.