I am responsible for conducting provenance research on all objects in our permanent collection. Provenance research is important to ensure the museum has the legal and ethical right to hold that object in its collection. Tracing the history of ownership can also enrich our understanding of the object itself by addressing such issues as authenticity, context of use, and cultural significance. Personally, I love just being able to tell the rich life story of an object.

So, what does the process of provenance research look like? While every case is different, I always start with the object itself. I examine it for any stickers, labels, or marks. If the work arrived at the museum on a mount or a backboard, this also needs to be examined. Dealers, museums, and private collectors may have marked an object or mount with their distinctive sticker or number that can allow you to trace ownership history.

After examining the object and any accouterment, I then move on to the files kept by the Registrar’s Office. When an object first arrives at the museum, we try to get as much information and documentation from the donor or seller as possible. Some attempts are more successful than others. In the files, I am looking for shipping documentation, customs forms, invoices, and sales receipts. Photographs showing the object in situ, in someone’s house, or on exhibition can be very helpful in determining how long an object has been out of its country of origin. Sometimes the files also contain correspondence from previous owners or scholars who have studied the object in the past.

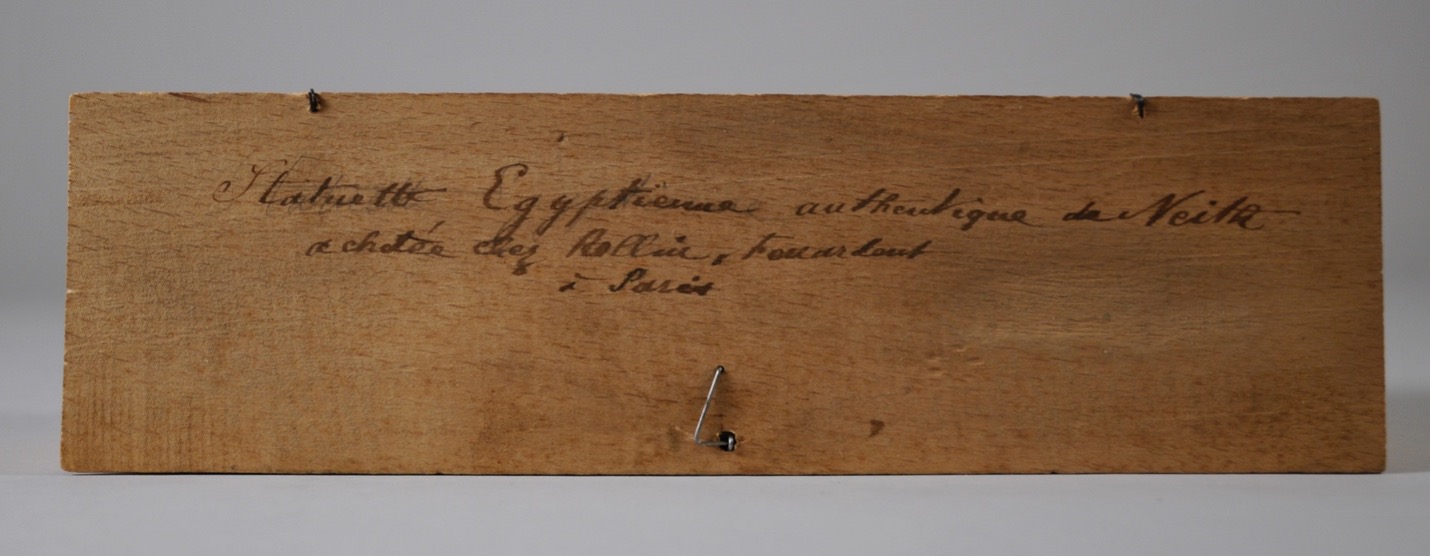

Hopefully, the object and the files have given me a trail to follow and names to research. If not, it can be helpful to research other objects from the same archaeological or cultural site, objects of the same type, or objects with a similar provenance. Luckily, in 2024, there are more digital resources and databases available than ever before. I do still spend a fair amount of time combing through my collection of past auction catalogues as well as Emory’s vast library holdings. When conducting my research, it is important that I track down as much information about an object as possible. I must also independently verify this information. Take, for example, our Egyptian sculpture that came to the museum in a box that said it was purchased from Rollin & Feuardent, Paris (2012.046.001). I cannot take this information as fact - I must find independent corroboration that the sculpture moved through the gallery. To date, I have yet to find proof. This does not mean the object is problematic. It simply means I do not have all the information at this time. I revisit objects like this periodically as new resources, research, and information are made available.

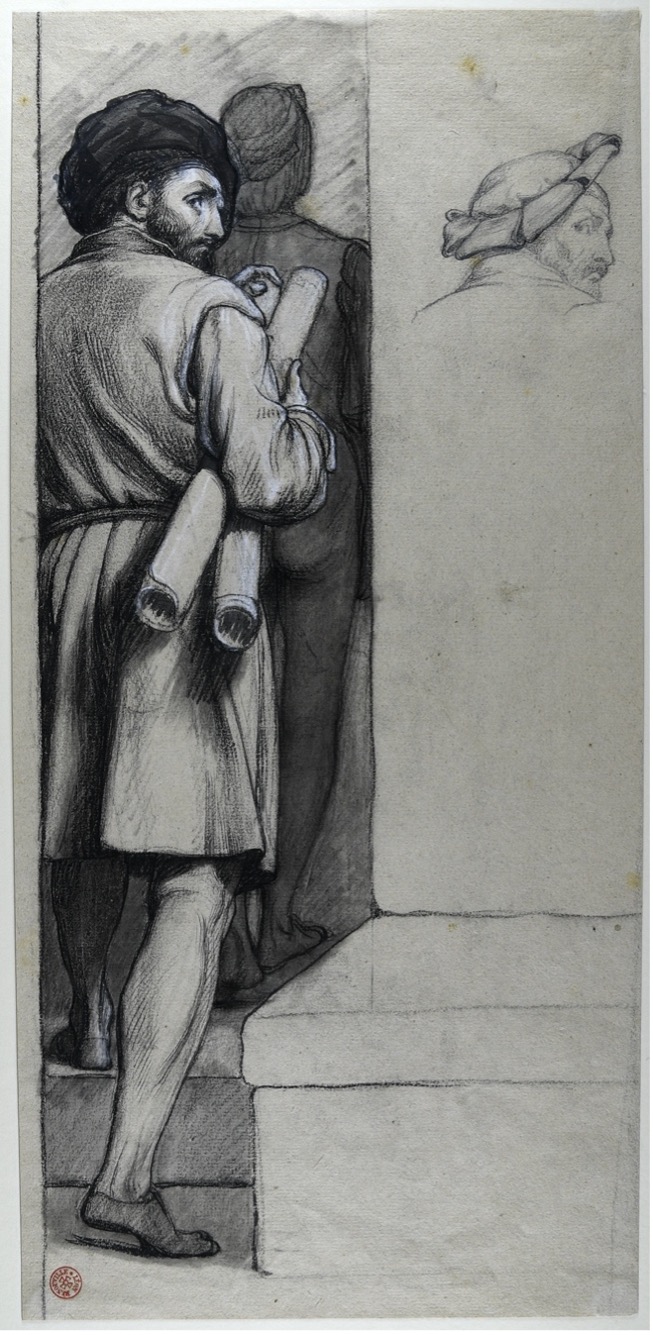

Note the red collector’s mark of Francois Leon Benouville (1821-1859) in the lower left corner.

The handwritten note states the object was purchased from Rollin & Feuardent, Paris (active 1867-1953).