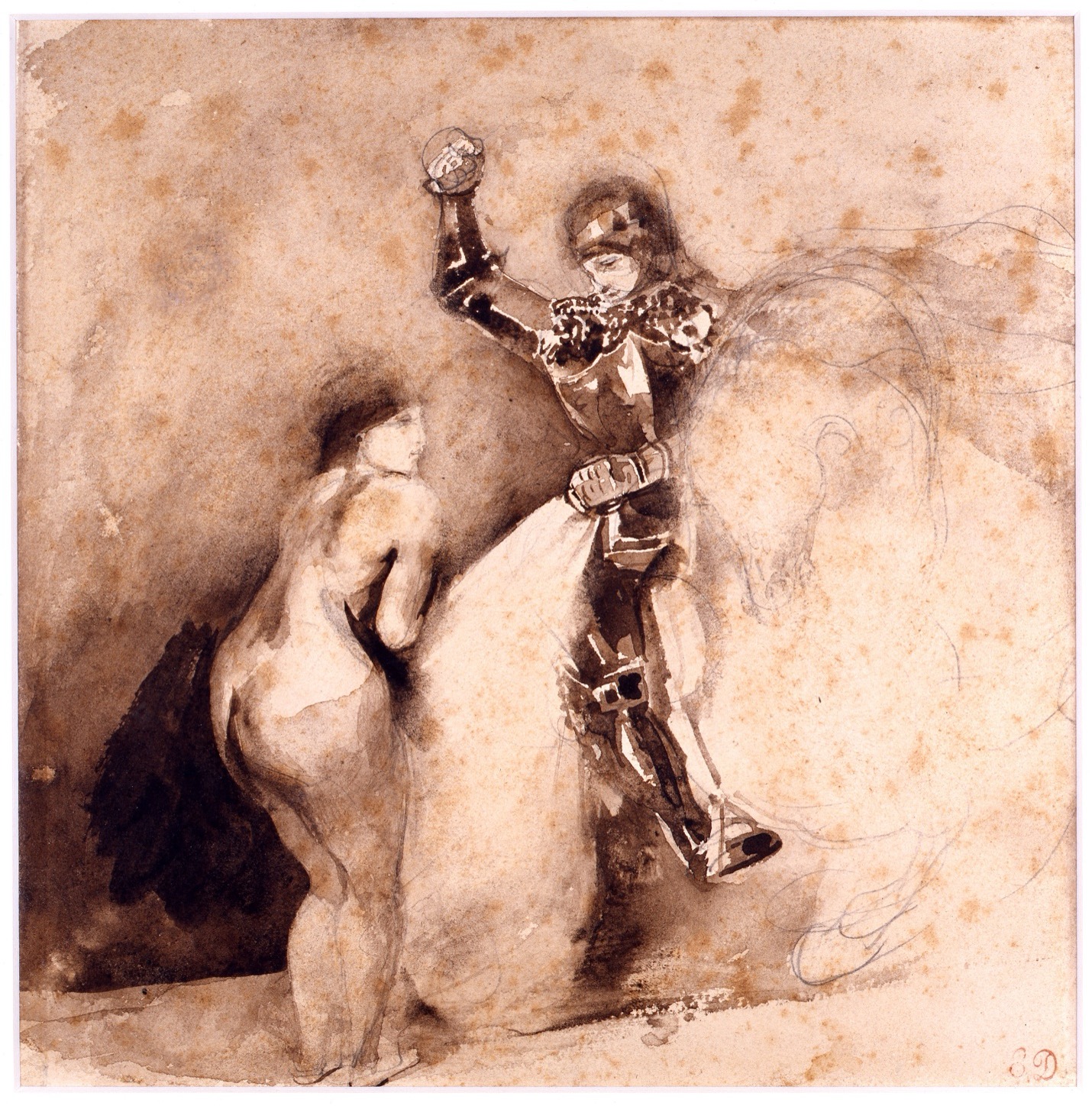

Last month, I investigated the provenance of a possible Delacroix drawing in our collection. We have one other work purported to be by Delacroix, so I figured I might as well tackle that one as well. The beginning of their stories is identical, as is their end, since they both found their way to the Carlos. However, what happened in between is very different.

Looking at the red ED stamped in the lower right corner of the Study for Marphisa (1998.017), we start off with the same provenance as last month’s work: this drawing was found in Delacroix’s studio after his death and was up for sale in Paris in 1864. For the next sixty-six years, I have no idea where our drawing was or who it was with. The first solid bit of provenance information comes from a 1930 German publication. According to the publication, the drawing (which is illustrated) comes from the collection of J.W. Böhler and was being shown in an exhibition organized by Paul Cassirer in Berlin. Paul Cassirer (1871–1926) was a German art dealer who was well known in Europe for promoting artists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne. After his premature death in 1926, Cassirer’s Berlin gallery was run by his partners Grete Ring (1882–1952) and Walter Feilchenfeldt (1894–1953).

After Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany in 1933, the Nazis began the process of Aryanization. Using legislation, propaganda, and fear, the Nazis forced the “voluntary” transfer of businesses from Jewish to Non-Jewish owners. To avoid this fate, Ring and Feilchenfeldt liquidated the Cassirer Gallery in Berlin. They took the remaining stock and assets to Amsterdam in the Netherlands. The Carlos drawing was represented by the Cassirer Gallery outside of Germany for the remainder of the 1930s.

In addition to businesses, the Nazis also set their sights on movable property such as art. In response to the widespread systematic looting of Europe’s art, the United States' Office of Strategic Services (OSS) formed the Art Looting Investigation Unit (ALIU). The unit was dedicated to uncovering information about Nazi looting networks and the restitution of stolen art. In addition to reports that are still valuable to provenance researchers today, the ALIU also produced a list of Red Flag Names. On the list is Julius Harry Böhler (1907-1979), the son of J.W. Böhler, the reported owner of the Carlos drawing in 1930. Julius Wilhelm Böhler (1883-1966) was a second-generation German art dealer based out of Munich. In 1919, J.W. moved to Lucerne, Switzerland and founded Kunsthandel AG Luzern with Fritz Steinmeyer (1880-1959). His son Julius Harry managed the Munich business during the Nazi Period.

After World War II, the drawing next appeared in Cambridge, Massachusetts. From January 11 to February 25, 1958, The Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University put on an exhibition of works, including the Carlos drawing, from the collection of Curtis O. Baer. Curtis Baer (1898-1976) was a German businessman who emigrated to the United States in 1940. He built a renowned collection of drawings in the 1950s and 1960s. It was the Baer family who donated Study for Marphisa to the Carlos in 1998.

I have checked lootedart.com as well as the FBI and Interpol databases to see if the drawing has been reported as stolen. The Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte in Munich, Germany holds a photo archive, object files, and documents related to works traded by Julius Böhler’s gallery from 1903 to 1994. Records related to transactions until 1948 are available online, but there is nothing associated with Marphisa. There is currently no evidence that the Carlos’s Study for Marphisa is connected with Nazi looting, but its presence in Europe in the 1930s and its association with the Böhler family is a somewhat uncomfortable part of its story.